Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

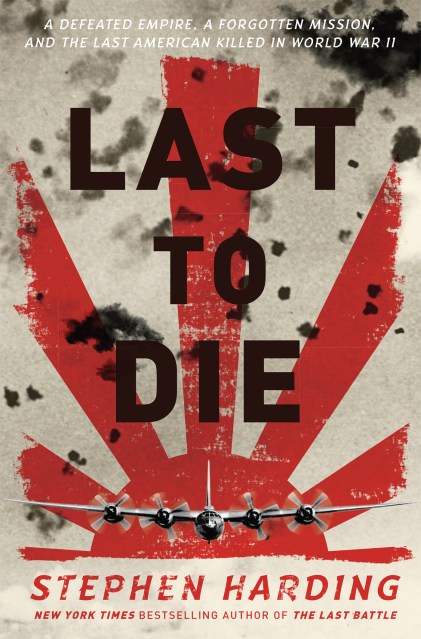

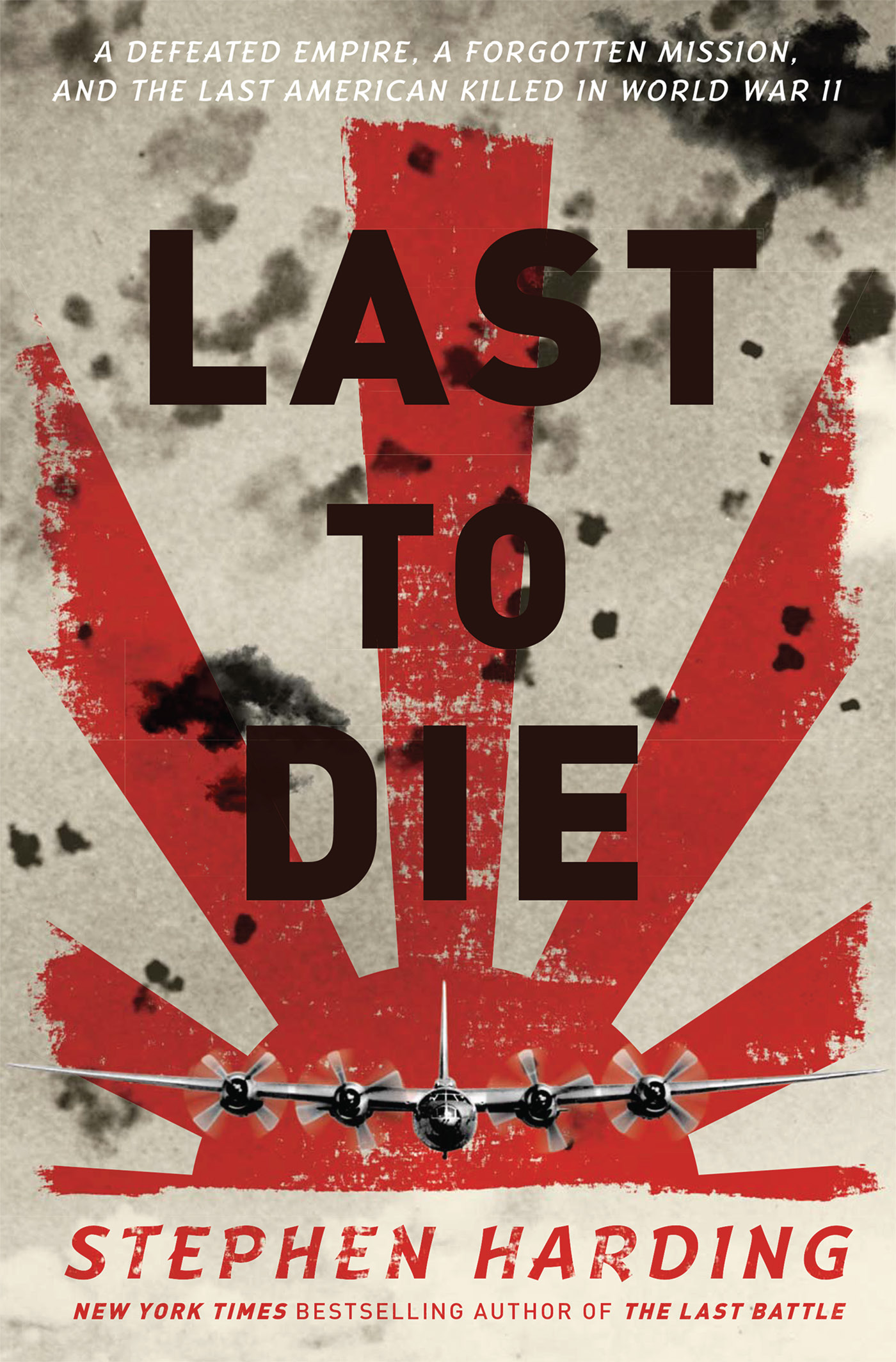

Last to Die

A Defeated Empire, a Forgotten Mission, and the Last American Killed in World War II

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $21.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 14, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

An aerial gunner who had already survived several combat missions, Marchione’s death was the tragic culmination of an intertwined series of events. The plane that carried him that day was a trouble-plagued American heavy bomber known as the B-32 Dominator, which would prove a failed competitor to the famed B-29 Superfortress. And on the ground below, a palace revolt was brewing and a small number of die-hard Japanese fighter pilots decided to fight on, refusing to accept defeat.

Based on official American and Japanese histories, personal memoirs, and the author’s exclusive interviews with many of the story’s key participants, Last to Die is a rousing tale of air combat, bravery, cowardice, hubris, and determination, all set during the turbulent and confusing final days of World War II.

Genre:

-

Praise for Last to Die

Booklist, 6/1/15

“Harding, a military-affairs journalist, has woven together letters, interviews with family and friends, and both Japanese and American military records to provide an intense, quietly moving, and, of course, sad chronicle of a young life cut short…Harding treats the youth with admiration and affection that elicits compassion without becoming cloying or melodramatic. This is a superb look at the life and death of one young man among millions of others who loved, were loved by others, and died too soon.”

Kirkus Reviews, 6/15/15

“[Harding] seems to be making a specialty of the forgotten closing episodes of WWII…In a neat blend of military and technological history, Harding links Marchione's story to the development of the aircraft he staffed, a lumbering target called the Consolidated Dominator…A worthy sortie that explores a curtain-closing moment in history that might have gone very badly indeed.”

Publishers Weekly, 6/22/15

“[A] meticulously researched account of the days following Japan's surrender… [Harding] relates his gripping account of the fight between Japanese and American forces in breathless detail, and the tale is impressive and inspiring, as is Harding's determination to tell it.”

- On Sale

- Jul 14, 2015

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780306823398

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use