By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

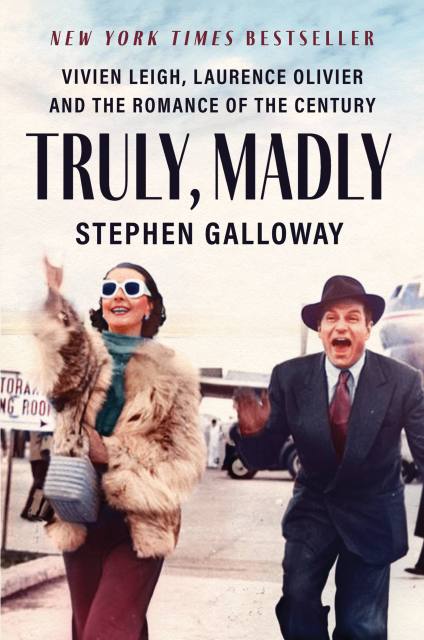

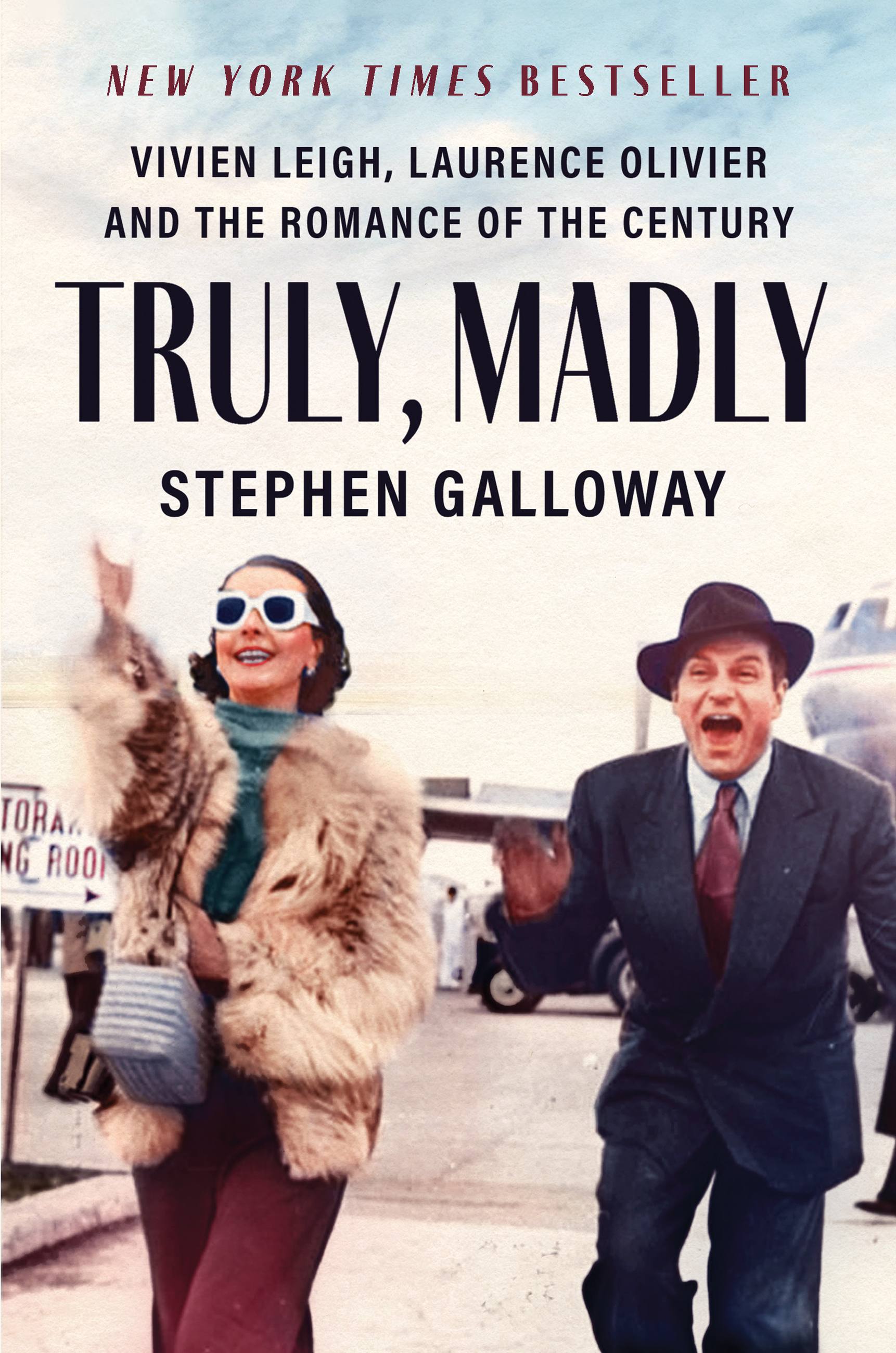

Truly, Madly

Vivien Leigh, Laurence Olivier, and the Romance of the Century

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 22, 2022

- Page Count

- 416 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538731970

Price

$30.00Price

$38.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 22, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A New York Times Bestseller

“A “well rounded and entertaining” (New York Times) Hollywood biography about the passionate, turbulent marriage of Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh.

In 1934, a friend brought fledgling actress Vivien Leigh to see Theatre Royal, where she would first lay eyes on Laurence Olivier in his brilliant performance as Anthony Cavendish. That night, she confided to a friend, he was the man she was going to marry. There was just one problem: she was already married—and so was he.

TRULY, MADLY is the biography of a marriage, a love affair that still captivates millions, even decades after both actors’ deaths. Vivien and Larry were two of the first truly global celebrities – their fame fueled by the explosive growth of tabloids and television, which helped and hurt them in equal measure. They seemed to have it all and yet, in their own minds, they were doomed, blighted by her long-undiagnosed mental-illness, which transformed their relationship from the stuff of dreams into a living nightmare.

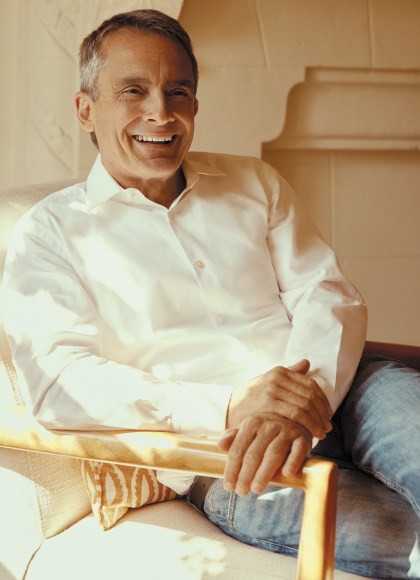

Through new research, including exclusive access to previously unpublished correspondence and interviews with their friends and family, author Stephen Galloway takes readers on a bewitching journey. He brilliantly studies their tempestuous liaison, one that took place against the backdrop of two world wars, the Golden Age of Hollywood and the upheavals of the 1960s — as they struggled with love, loss and the ultimate agony of their parting.

-

"[W]ell rounded and entertaining. . . To the couple’s tale of passion [Stephen Galloway] adds compassion, along with the requisite lashings of gossip. . . Galloway splices this material seamlessly with old interviews and enough new ones with those Of That Era, such as Korda and Hayley Mills, to inject some pep and freshness."New York Times

-

"Galloway, the former executive editor of the Hollywood Reporter, lifts himself clear of previous chronicles, including Olivier’s own self-lacerating memoirs, by supplementing firsthand accounts with retrospective diagnoses by experts like Kay Redfield Jamison and by tracing a genetic link to Leigh’s great-uncle, housed in a Kolkata asylum for much the same symptoms. More lucidly than ever, we can see how, in the grip of her own brain chemistry, Leigh quite literally lost her mind."The Washington Post

-

"Between the tabloid intrigue and the Shakespearean end is a compelling portrait of two people trying their best."Vanity Fair

-

"[Truly, Madly] is very much Leigh’s story, told most poignantly as the book narrows its scope to chronicle her decline. . . Galloway juggles the complex story energetically. He’s at his best when he takes a forensic approach to the relationship and to Leigh’s struggles."USA Today

-

"Gripping."Wall Street Journal

-

“In this deeply researched dual biography, Stephen Galloway uncovers the story of how the two stars–among the most famous in the world in their time—came together, captivated the world, and were ultimately torn apart. It's a fascinating look at the dueling powers of dizzying fame and true love.”Town & Country

-

"[A] richly detailed account of the fiery ascent and demise of one of Hollywood’s most glamorous couples. . . This page-turning biography is one to get swept up in."Publishers Weekly

-

"[A] dishy narrative about the tumultuous marriage of Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh. . . A good choice for lovers of theater and cinema—and for those who live for the drama."Kirkus Reviews

-

"[Truly, Madly] will greatly appeal to cinema buffs, theater aficionados, and fans of the doomed lovebirds."Library Journal

-

"A haunting, irresistible read."People Magazine

-

"Galloway traces the legends’ epic 20- year love story from its smoldering start to its bittersweet finish."Closer

-

“Stephen Galloway’s irresistible narrative begins with a brazen act of incendiary passion between two of the world’s most brilliant actors. But their love story turns self-destructive, faithless, and vengeful as Leigh descends into a madness that Olivier is powerless to prevent. As they turn on each other, Galloway captures with clear-eyed compassion all of the anguish of two beautiful people stripped of hope and pretense.”GLENN FRANKEL, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and author of Shooting Midnight Cowboy: Art, Sex, Loneliness, Liberation, and the Making of a Dark Classic

-

“A juicy show-business story like this demands a skilled storyteller and scrupulous researcher. Stephen Galloway is both of those things, which is why his book is so valuable.”LEONARD MALTIN, film critic and historian, author of Leonard Maltin’s Movie Guide

-

“This is a wonderful read with elegant prose and eloquent dish. Stephen Galloway has for many years been one of the foremost chroniclers of the American film industry. Here, he draws back the curtain on the passionate, complicated relationship between two of its most beloved stars, Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh, a dream pairing that turned into a nightmare.”WILLIAM FRIEDKIN, Oscar-winning director of The French Connection and The Exorcist

-

“One of the classic real-life movie star love stories, deeply romantic and inescapably tragic, is brought to vivid life in Stephen Galloway’s engrossing book. Thoroughly researched and engagingly written, it pulls us into the maelstrom and shows us the truth.”KENNETH TURAN, NPR film critic

-

“Galloway is a gifted storyteller, whose eye for the tiny details that reveal raw human emotion and struggle is extraordinary.”JANICE MIN, Contributing Editor, TIME

-

"[S]teamy and spellbinding. . . Truly, Madly is full of dish, glam and eccentricities. . . [A] fab read. Warning: have a handkerchief in hand."Los Angeles Blade

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use