Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

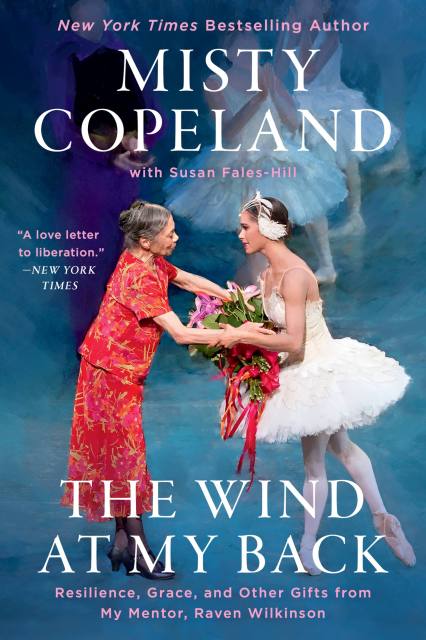

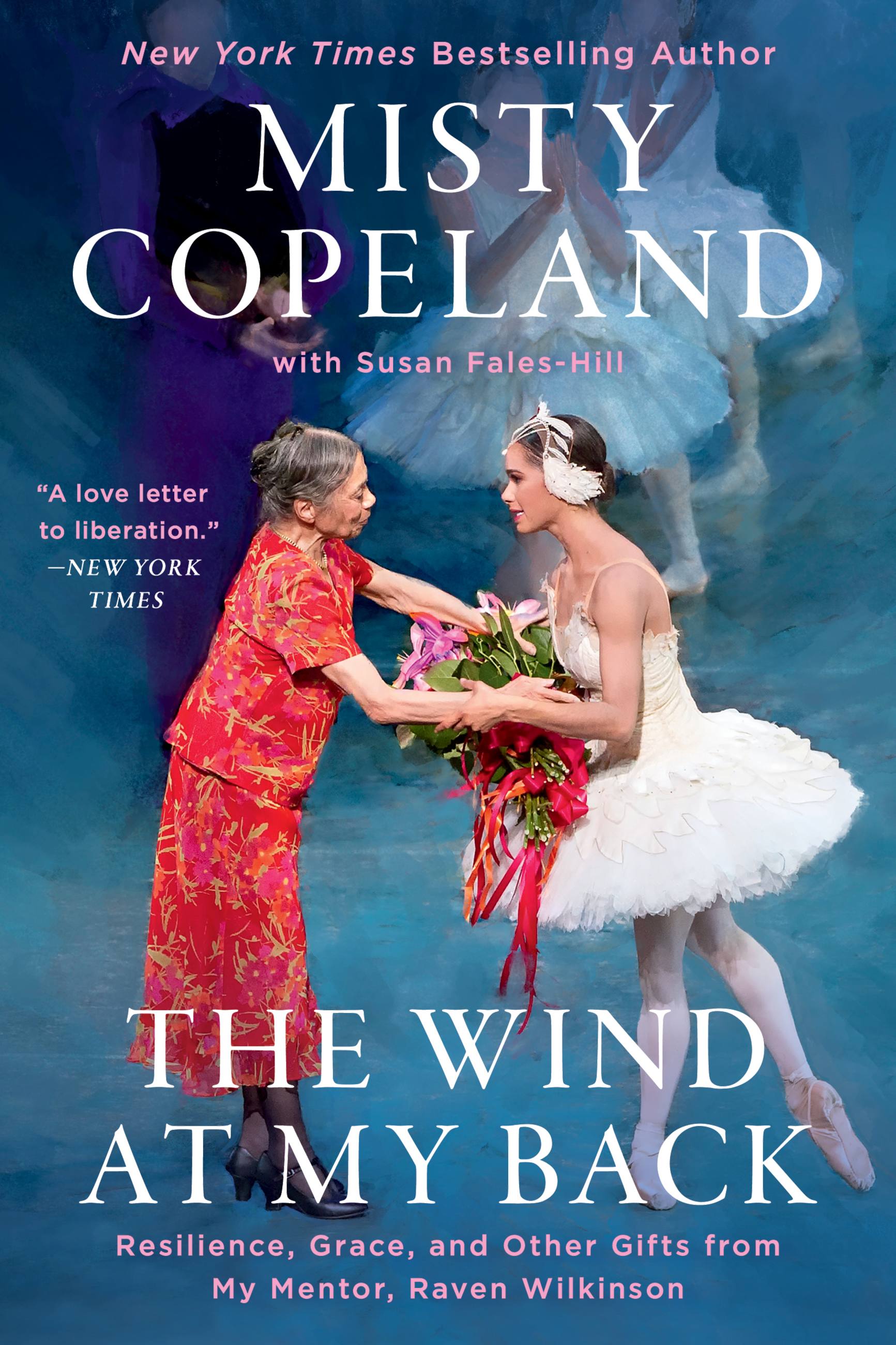

The Wind at My Back

Resilience, Grace, and Other Gifts from My Mentor, Raven Wilkinson

Contributors

With Susan Fales-Hill

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 3, 2023

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538753873

Price

$18.99Price

$23.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $18.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 3, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Misty Copeland made history as the first African-American principal ballerina at the American Ballet Theatre. Her talent, passion, and perseverance enabled her to make strides no one had accomplished before. But as she will tell you, achievement never happens in a void. Behind her, supporting her rise was her mentor Raven Wilkinson. Raven had been virtually alone in her quest to breach the all-white ballet world when she fought to be taken seriously as a Black ballerina in the 1950s and 60s. A trailblazer in the world of ballet decades before Misty’s time, Raven faced overt and casual racism, hostile crowds, and death threats for having the audacity to dance ballet.

The Wind at My Back tells the story of two unapologetically Black ballerinas, their friendship, and how they changed each other—and the dance world—forever. Misty Copeland shares her own struggles with racism and exclusion in her pursuit of this dream career and honors the women like Raven who paved the way for her but whose contributions have gone unheralded. She celebrates the connection she made with her mentor, the only teacher who could truly understand the obstacles she faced, beyond the technical or artistic demands.

A beautiful and wise memoir of intergenerational friendship and the impressive journeys of two remarkable women, The Wind at My Back captures the importance of mentorship, of shared history, and of respecting the past to ensure a stronger future.

-

“In warm, plain-spoken prose, Copeland details Wilkinson’s bravery . . . This book is a generous, sincere love letter to Wilkinson, who died in 2018, but it’s also a love letter to liberation . . . This bighearted memoir is an antidote to that marginalization.”New York Times

-

"Anyone lucky enough to have seen Misty dance knows the perfect balance of power, grace, joy and purpose that pours out from her. She’s no less wonderful a writer. This story of Misty and her muse, idol and mentor, the inimitable Raven Wilkinson, is a beautiful love letter and an inspiring tribute."Amanda Seyfried, actress

-

"Having a contemporary ballerina tell the story of one of the great pioneers of our art form and bear witness to their mutual love and respect is so moving. I laughed, I reminisced, I cried….A definite must read!!!”Lauren Anderson, Associate Director of Education & Community Engagement and former principal dancer at Houston Ballet

-

"What a courageous, authentic, and heartfelt story of the beautiful friendship between Misty Copeland and Raven Wilkinson, the ballerina who broke barriers in the 1950s with the Ballet Russe. Through the support of her mentor Ms. Wilkinson, Mrs. Copeland finds her deeper calling in paving the way for other black and brown dancers to fulfill their dreams in the art of ballet and beyond. Their story is truly inspiring."Susan Jaffe, Artistic Director Designee at American Ballet Theatre

-

“Misty shares her story, as well as Raven’s, with a transparency and authenticity that invites readers to join her in navigating the ballet world as a Black woman. She guides us through the struggles but leaves us with hope and beauty.”Darren Walker, president of the Ford Foundation

-

"Copeland celebrates her mentor’s wisdom as she shoulders the burdens and thrills of her historic career, and aims to inspire other dancers of color who face similar barriers as they pursue their passions . . . The strength that Copeland found in Wilkinson is moving, and she renders it gracefully throughout. This is an inspiring and insightful account.”Publishers Weekly

-

"A candid, instructive reflection on artistry, dedication, and race."Kirkus Reviews

-

"These pages are a heartfelt tribute to Wilkinson, who passed away in 2018, and an acknowledgment of her remarkable life and career. Copeland has gracefully accepted the challenge to continue to improve dance—and humanity—in honor of Wilkinson and all those who follow her.”Booklist

-

"Balletomanes will enjoy the book’s blow-by-blow accounts of Copeland’s mold-breaking performance of Swan Lake and of Wilkinson’s interactions with dance luminaries like Alicia Alonso . . . An accessible read that will surely be popular with Copeland’s many fans."Library Journal

-

"A love letter . . . infused with grace, both inside and out."Miami Times

-

"A beautiful memoir that captures the friendship between Copeland and Wilkinson, and shares the impact that their stories continue to have on the world of dance."Town & Country

-

"What’s beautiful about this memoir is seeing how these two women developed an unbreakable friendship . . . 5 out of 5 stars."Black Girl Nerds