Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

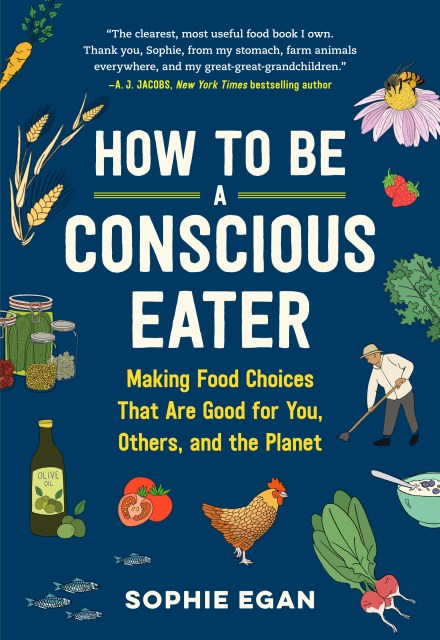

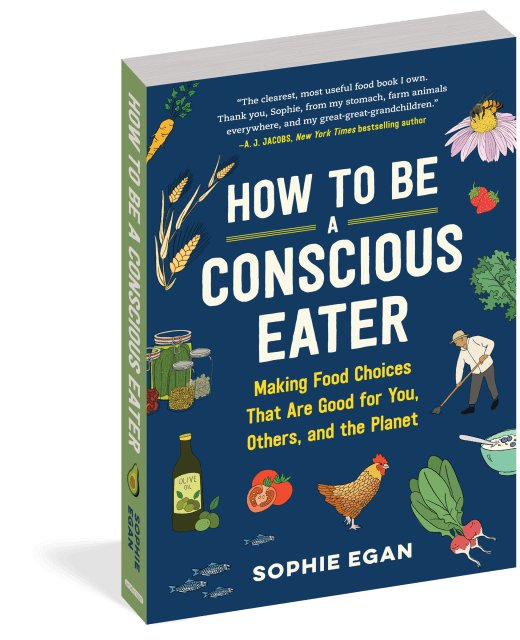

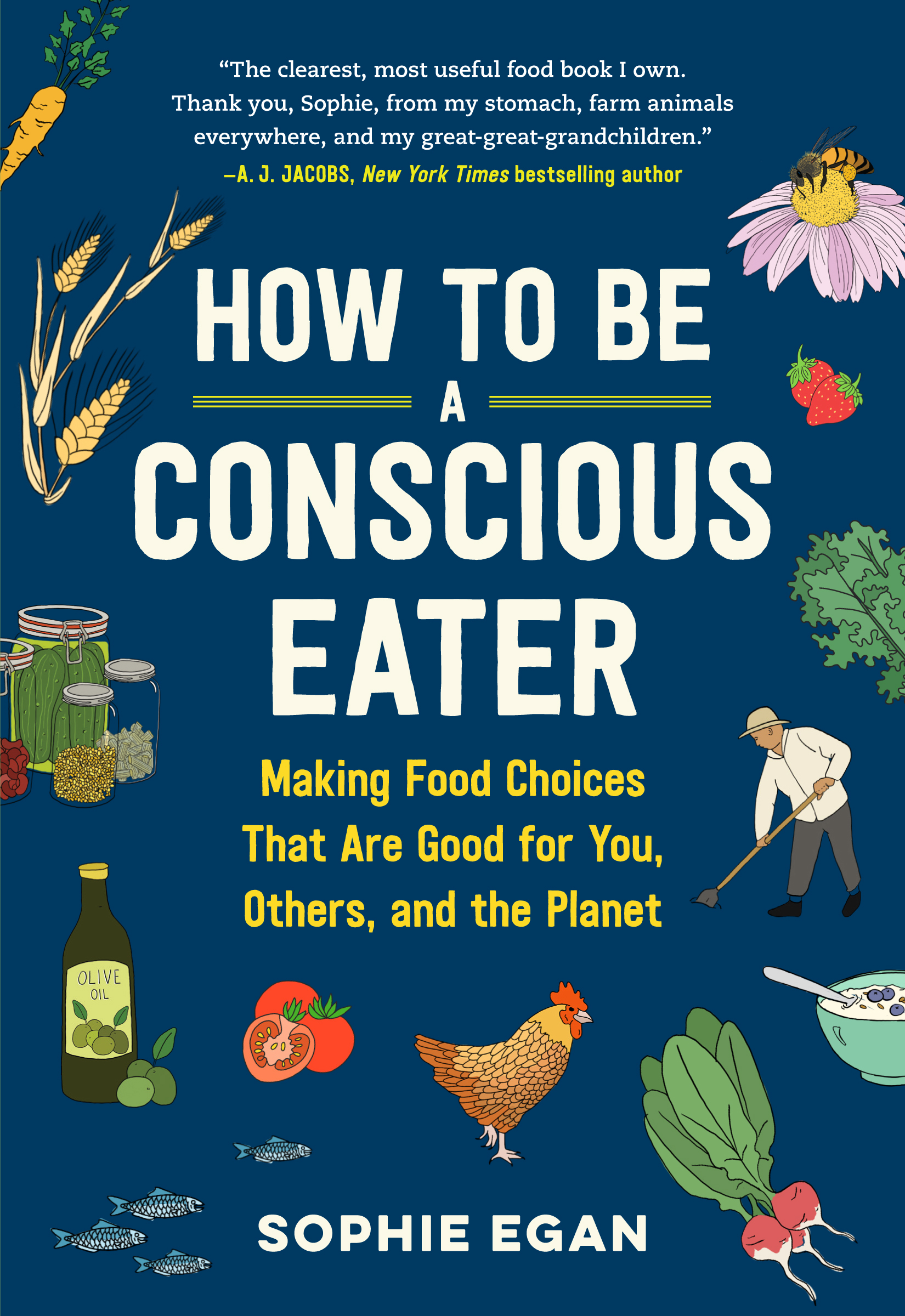

How to Be a Conscious Eater

Making Food Choices That Are Good for You, Others, and the Planet

Contributors

By Sophie Egan

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.95Price

$22.95 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.95 $22.95 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 17, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A radically practical guide to making food choices that are good for you, others, and the planet.

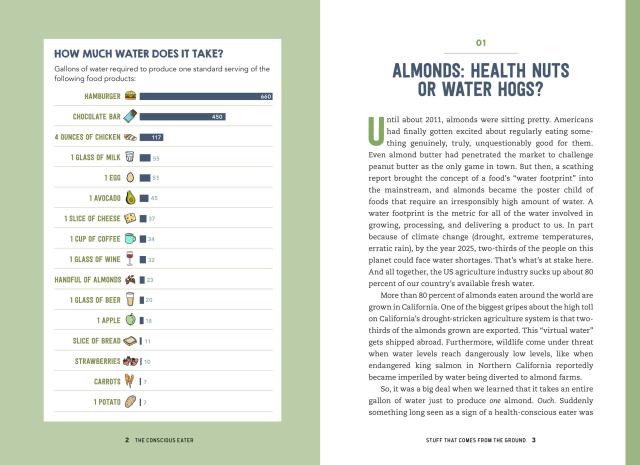

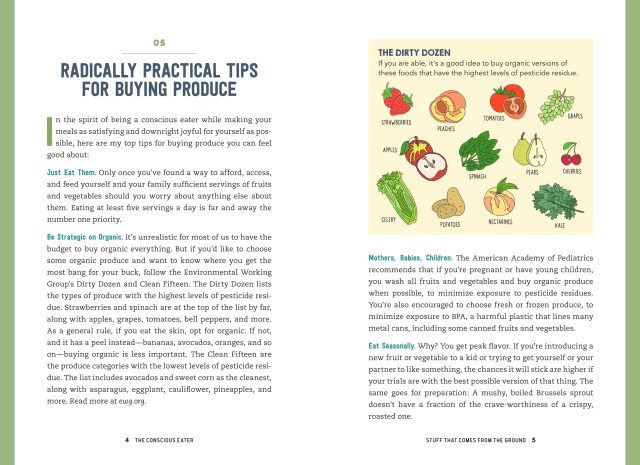

Is organic really worth it? Are eggs ok to eat? If so, which ones are best for you, and for the chicken—Cage-Free, Free-Range, Pasture-Raised? What about farmed salmon, soy milk, sugar, gluten, fermented foods, coconut oil, almonds? Thumbs-up, thumbs-down, or somewhere in between?

Using three criteria—Is it good for me? Is it good for others? Is it good for the planet?—Sophie Egan helps us navigate the bewildering world of food so that we can all become conscious eaters. To eat consciously is not about diets, fads, or hard-and-fast rules. It’s about having straightforward, accurate information to make smart, thoughtful choices amid the chaos of conflicting news and marketing hype. An expert on food’s impact on human and environmental health, Egan organizes the book into four categories—stuff that comes from the ground, stuff that comes from animals, stuff that comes from factories, and stuff that’s made in restaurant kitchens. This practical guide offers bottom-line answers to your most top-of-mind questions about what to eat.

“The clearest, most useful food book I own.”—A. J. Jacobs, New York Times bestselling author

Genre:

-

“…smart and sensible approach to eating consciously…” —Michael Pollan, New York Times bestselling author "If you’ve ever stalled out in the refrigerated aisle debating the environmental merits of oat vs. almond milk, add this book to your bedside table. Sophie Egan provides clear, non-judgmental information... It’s a practical guide that empowers readers to understand the plethora of labels and claims out there and make informed food choices every time you go to the store." —Bon Appetit.com

“The clearest, most useful food book I own. Thank you, Sophie, from my stomach, farm animals everywhere, and my great-great-grandchildren.”

—A.J. Jacobs, New York Times bestselling author

“Thought-provoking… Egan displays a talent for making the environmental complexities of food choices comprehensible… [A] thorough primer to combining health consciousness and environmental responsibility.” – Publishers Weekly starred review

“Egan (Devoured: How We Eat Defines Who We Are) presents a voice of reason in the cacophony of advice about food and diet that surrounds us…Recommended for everyone who eats, particularly those who hope to improve their own health and the planet’s by doing so.”—Library Journal starred review

“Readers will find much to take away, including reminders that our consumer behavior can drive change and that what's good for us and good for the planet often align.”—Booklist

- On Sale

- Mar 17, 2020

- Page Count

- 280 pages

- Publisher

- Workman Publishing Company

- ISBN-13

- 9781523507382

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use