Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

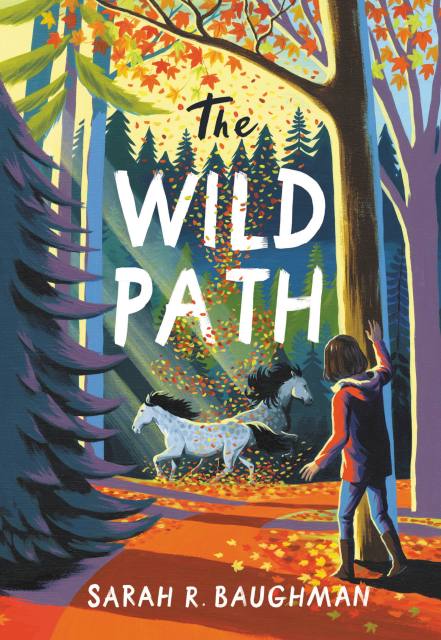

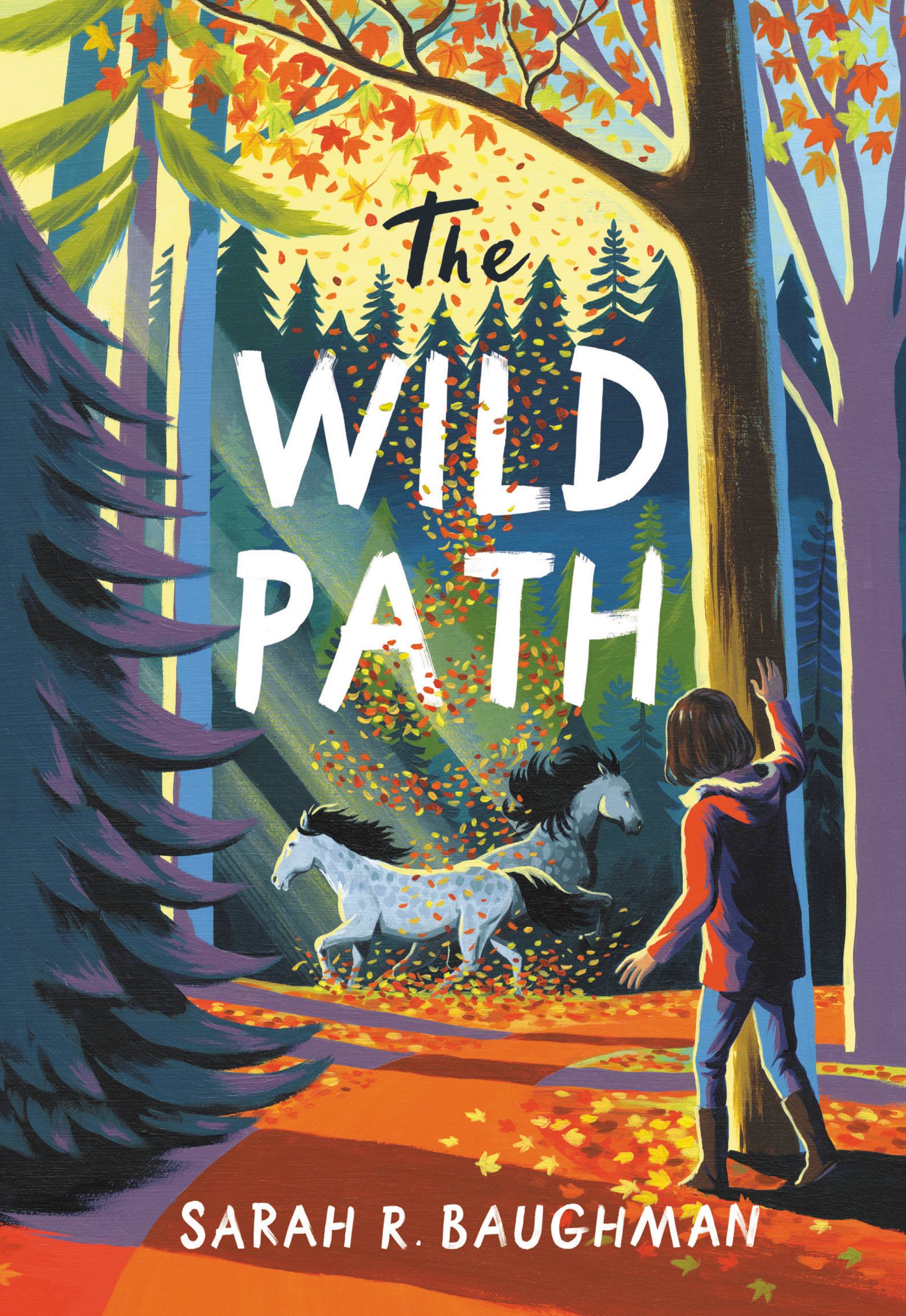

The Wild Path

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$7.99Price

$11.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $7.99 $11.99 CAD

- ebook $7.99 $9.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 26, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Twelve-year-old Claire Barton doesn't like the "flutter feeling" that fills her chest when she worries about the future, but she knows what she loves: the land that's been in her family for three generations; her best friend Maya; her family's horses, Sunny and Sam; and her older brother Andy. That's why, with Andy recently sent to rehab and her parents planning to sell the horses, Claire's world feels like it might flutter to pieces.

When Claire learns about equine therapy, she imagines a less lonely future that keeps her family together, brother and horses included. But, when she finds what seem to be mysterious wild horses in the woods behind her house, she realizes she has a bitmore company than she bargained for. With this new secret—and a little bit of luck—Claire will discover the beauty of change, the power of family, and the strength within herself.

Genre:

-

Praise for The Wild Path:Dusti Bowling, bestselling author of Insignificant Events in the Life of a Cactus and The Canyon's Edge

"A gorgeous, colorful fall setting, a mystery surrounding wild horses roaming the woods, and a sensitive representation of a family contending with addiction all add up to make this not only a magical story, but an important one." -

Praise for The Light in the Lake:Kirkus Reviews, starred review

* "Baughman convincingly portrays the varied reactions to the findings as well as everybody's desire for the lake to thrive.... Compassionately told, this compelling debut brings to life conservation issues and choices young readers will confront as adults." -

* "In Baughman's skillful handling, Addie's memories of her brother and her first-person voice are both heartbreaking and hopeful. The novel offers a gentle, introspective exploration of grief and the wonder and fragility of nature, creating a beautiful and dynamic world in which the scientific method and magic coexist."Publishers Weekly, starred review

-

"The Light in the Lake is a moving novel that skillfully balances magic and science, and loss and hope. Sarah Baughman has created a brave, smart protagonist readers are sure to connect with and root for in her compelling debut."Supriya Kelkar, award-winning author of Ahimsa and American as Paneer Pie

-

"Haunting, memorable and full of mystery, The Light in the Lake is a brilliant combination of beautiful, lyrical prose and a compelling, exciting story. Baughman has created complex characters with real, deep emotions and a picturesque setting that will make readers feel as if they are at Maple Lake with Addie."BookPage

-

"Told in prose as luminous as the mysterious creature Addie searches for, The Light in the Lake shines with heart, hope, and just a touch of magic."Cindy Baldwin, author of Where the Watermelons Grow

-

"A complex take on science, magic, grief, and family for fans of thoughtful realistic fiction in the vein of Kathi Appelt's, Erin Entrada Kelly's, and Ali Benjamin's novels."School Library Journal

-

"The Light in the Lake radiates with heart and hope. As Addie's tender memories of her brother intertwine with the magic she uncovers in her town's beloved lake, we're led on a moving exploration of science, grief, and self-discovery. A poignant, lyrical story that tugs at the heartstrings."Mae Respicio, award-winning author of The House That Lou Built

-

"Baughman paints with authenticity the grief of Addie.... Addie's unabashed love for science makes her a pleasingly STEM-focused heroine, and her quest to solve Amos' questions about the lake is interesting and admirable."BCCB

-

"Drawing on the wonder of science and the power of magic, Baughman has crafted a story that plunges readers into the deep places of the heart. In The Light in the Lake she reminds us that not even the depths of loss can prevent the rise of light and discovery. A poignant story, filled to the brim with hope."Beth Hautala, author of Waiting for Unicorns and The Ostrich and Other Lost Things

- On Sale

- Oct 26, 2021

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9780316422437

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use