By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

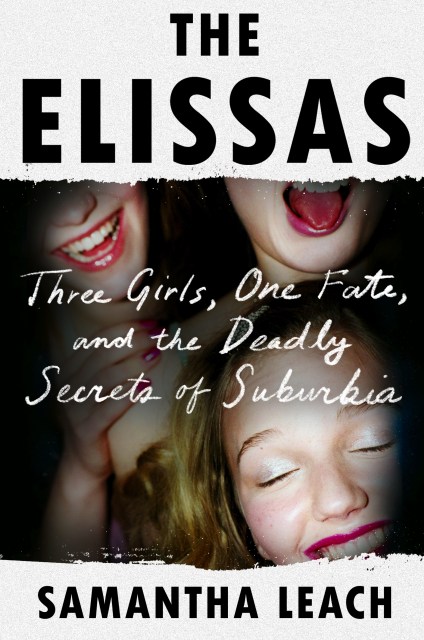

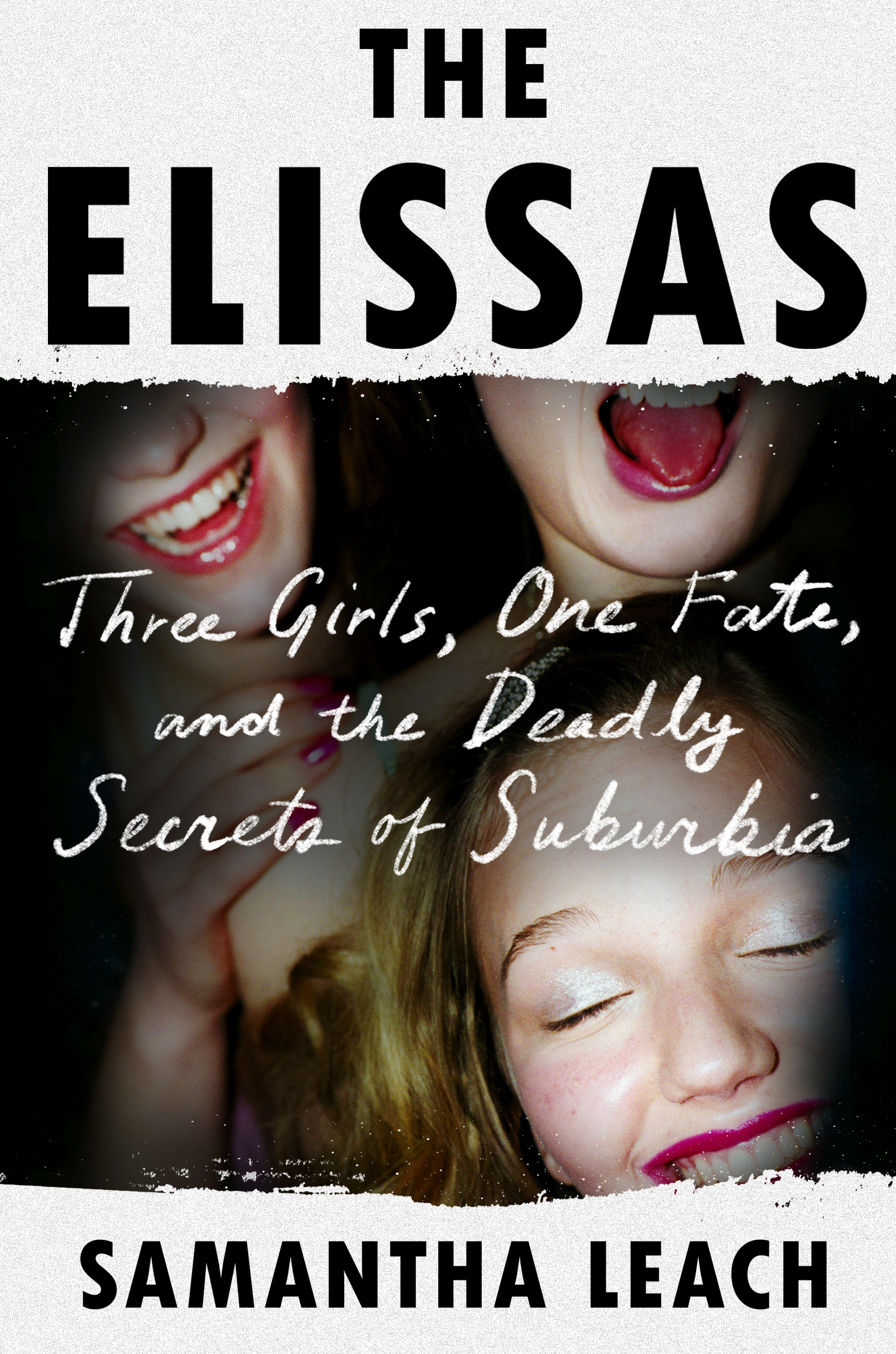

The Elissas

Three Girls, One Fate, and the Deadly Secrets of Suburbia

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 6, 2023

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Legacy Lit

- ISBN-13

- 9780306826917

Price

$29.00Price

$37.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 6, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Nylon’s “June 2023’s Must-Read Book Releases”

Pure Wow’s “11 Books We Can’t Wait to Read in June”

The Skimm’s “17 of Our Favorite Books Coming Out This Summer”

Glamour’s “15 Best Nonfiction Books of 2023, So Far”

Bustle’s “Most Anticipated Books Of Spring & Summer 2023”

Harper’s Bazaar’s “23 Best Summer Beach Reads of 2023”

Zibby Mag’s “Most Anticipated Spring and Summer Books”

A New York Post Best Books of the Week selection

Three suburban girls meet at a boarding school for troubled teens.

Eight years later, they were dead.

Bustle editor Samantha Leach and her childhood best friend, Elissa, met as infants in the suburbs of Providence, Rhode Island, where they attended nursery, elementary school, and temple together. As seventh graders, they would steal drinks from bar mitzvahs and have boys over in Samantha’s basement—innocent, early acts of rebellion. But after one of their shared acts, Samantha was given a disciplinary warning by their private school while Elissa was dismissed altogether, and later sent away. Samantha did not know then, but Elissa had just become one of the fifty-thousand-plus kids per year who enter the Troubled Teen Industry: a network of unregulated programs meant to reform wealthy, wayward youth.

Less than a year after graduation from Ponca Pines Academy, Elissa died at eighteen years old. In Samantha’s grief, she fixated on Elissa’s last years at the therapeutic boarding school, eager to understand why their paths diverged. As she spoke to mutual friends and scoured social media pages, Samantha learned of Alyssa and Alissa, Elissa’s closest friends at the school who shared both her name and penchant for partying, where drugs and alcohol became their norm. The matching Save Our Souls tattoo all three girls also had further fueled Samantha’s fixation, as she watched their lives play out online. Four years after Elissa’s death, Alyssa died, then Alissa at twenty-six.

In The Elissas, Samantha endeavors to understand why they ultimately met a shared, tragic fate that she was spared, in turn, offering a chilling account of the secret lives of young suburban women.

-

“Like the Furies and the Fates of Greek mythology, the subjects of Samantha Leach’s The Elissas are troubled and troubling young women enacting a drama that feels both ancient and inevitable. If the addiction narrative has ascended to the level of myth in America (and it’s all too easy to argue that it has), then Elissa, Alyssa and Alissa are a familiar archetype: poor little rich girls, young and rebellious, their problems surely solvable by Daddy’s money. In this smart and gripping debut, Leach refreshes a familiar heartbreak by weaving the stories of these three lost young women into a larger, more complicated and ultimately tragic narrative of a nation not so much losing the war on drugs as on a death march every bit as doomed as the last battles in Sparta.”New York Times

-

“…a searing exposé.”Publisher’s Weekly (Starred Review)

-

"An intimate, moving narrative peppered with harsh statistics, love, angst, and the author’s own admirable vulnerability."Library Journal (Starred)

-

“[Leach] develops sensitive portraits of each girl and suggests how social pressures, combined with health and environmental factors, conspired to damage the minds and then destroy the bodies of three vulnerable young women. A poignant and heartfelt mix of sociology and memoir.”Kirkus

-

“Leach takes the reader through this harrowing, heartbreaking story . . . With great care, she reveals the paths that led these girls’ deaths at 18, 23, and 26, when their lives should have just been beginning. The loss is enormous, and Leach painstakingly, lovingly, braids their stories into one indelible work.”Glamour

-

“The Elissas is elegiac and investigative in equal measure. Leach channels her grief from her early friend’s loss into compassionate, poignant reporting—and one of the best nonfiction books of the summer.”Harper's Bazaar

-

"In this urgent expose of the long-term trauma caused by the troubled teen industry, Samantha Leach investigates the life of a close friend lost to addiction, and the two girls who shared a friendship with her at boarding school and also perished far too young. These lives cut short unmask the brutal social control behind the concept of reform schools, where well-off parents pay thousands to have their children beaten, starved, abused, and otherwise coerced into toeing the line."CrimeReads

-

"When Bustle editor at large Samantha Leach’s childhood best friend, Elissa, passed away at the age of eighteen, she was understandably devastated and confused. In seeking answers about her friend’s untimely death, Leach uncovered a complex story; the years before she died, Elissa had been living at one of the many unregulated boarding programs that make up America’s scandal-ridden troubled teen industry. As Leach further investigated what happened to her friend, she learned of Alyssa and Alissa, Elissa’s closest friends at the school who, in addition to sharing a penchant for partying and matching Save Our Souls tattoos, also died young, in their early twenties. The Elissas explores the secret lives of wealthy young suburban women, the impacts of reform school, and the fate that led to their paths diverging in such a tragic way."W Magazine

-

"Leach’s exploration of the troubled teen industry and suburban girlhood is heart-wrenching, culminating in a book in the same addictive vein as Lisa Taddeo’s Three Women."Nylon

-

“[A] high-wire act of writing about privilege and the pain of losing your oldest friend.”Vogue

-

“Leach was deeply inspired by Three Women by Lisa Taddeo, but unlike Taddeo’s book, The Elissas reaches beyond the lives of Elissa, Alyssa, and Alissa and examines the larger forces that shaped their course of their lives, that sparked and fed their rebellion: pop culture, including Leach and Elissa’s treasured The Simple Life, the Troubled Teen Industry, and the opioid epidemic.”Rumpus

-

“Chilling . . . Drawing on interviews with parents, friends and acquaintances, Leach details how the girls ended up at Ponca Pines and how the system failed them so severely. It’s a powerful indictment of how little we understand about treating addiction and other mental health issues.”PureWow

-

“In The Elissas, Samantha Leach writes with great compassion about the pressures on girls to live up to today’s punishing beauty standards. With insight and precision, Leach exposes the ways in which the so-called Troubled Teen Industry preys upon girls’ vulnerability and capitalizes on their parents’ naivete—and bank accounts. The Elissas is both a deeply personal story of loss and an indictment of the societal forces that contributed to robbing a young woman of those closest to her. Leach’s investigation into how the Elissas perished adds much to our understanding of how dangerous misogyny can be to the health and well-being of girls and young women.”Nancy Jo Sales, New York Times bestselling author of American Girls and Nothing Personal

-

“Rebellious and real, troubled yet hopeful, The Elissas presents an abiding portrait of friendship forged in the coercive clutches of upper and middle class America. From the basements of suburban homes to the innermost workings of the Troubled Teen industry, Samantha Leach holds a magnifying glass to adolescent girlhood and the capitalist forces that equate youth with desirability, beauty with success, safety with secrecy.”Allie Rowbottom, author of Aesthetica and Jell-O Girls

-

“A decade after losing her best friend, Samantha Leach is haunted by her loss. Why was she spared the fate that befell Elissa? In incisive, fearless prose Leach investigates the realities of the Troubled Teen Industry and reevaluates her own role in the chaos and rebellion of adolescence. There are hard truths about girlhood, friendship, and boundaries in The Elissas, each of them heart-rending and ultimately, inspiring.”Stephanie Danler, New York Times bestselling author of Sweetbitter and Stray

-

“Samantha Leach's The Elissas is a compelling fusion of memoir, reportage and cultural analysis that serves as both a damning indictment of the exploitative troubled teen industry and a compassionate look at the young people who have fallen prey to it.”Sam Lansky, author of The Gilded Razor

-

"It's a shocking story...I think there is so much honesty and vulnerability in the book. Even now, I think Gen Z readers will relate to the pressures and the culture and the honesty that Leach has around her relationship to shame."Emily Ratajkowski

The Elissas - Book Club Kit

A bookclub resource for THE ELISSAS by Samantha Leach - including questions, supplemental readings, and other extras!

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use