Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

The Glamour of Grammar

A Guide to the Magic and Mystery of Practical English

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 16, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

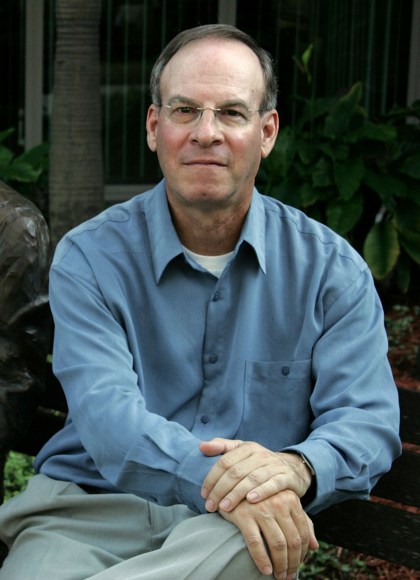

Early in the history of English, the words “grammar” and “glamour” meant the same thing: the power to charm. Roy Peter Clark, author of Writing Tools, aims to put the glamour back in grammar with this fun, engaging alternative to stuffy instructionals. In this practical guide, readers will learn everything from the different parts of speech to why effective writers prefer concrete nouns and active verbs.

The Glamour of Grammar gives readers all the tools they need to”live inside the language” — to take advantage of grammar to perfect their use of English, to instill meaning, and to charm through their writing. With this indispensable book, readers will come to see just how glamorous grammar can be.

The Glamour of Grammar gives readers all the tools they need to”live inside the language” — to take advantage of grammar to perfect their use of English, to instill meaning, and to charm through their writing. With this indispensable book, readers will come to see just how glamorous grammar can be.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Aug 16, 2010

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Little Brown Spark

- ISBN-13

- 9780316089067

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use