Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

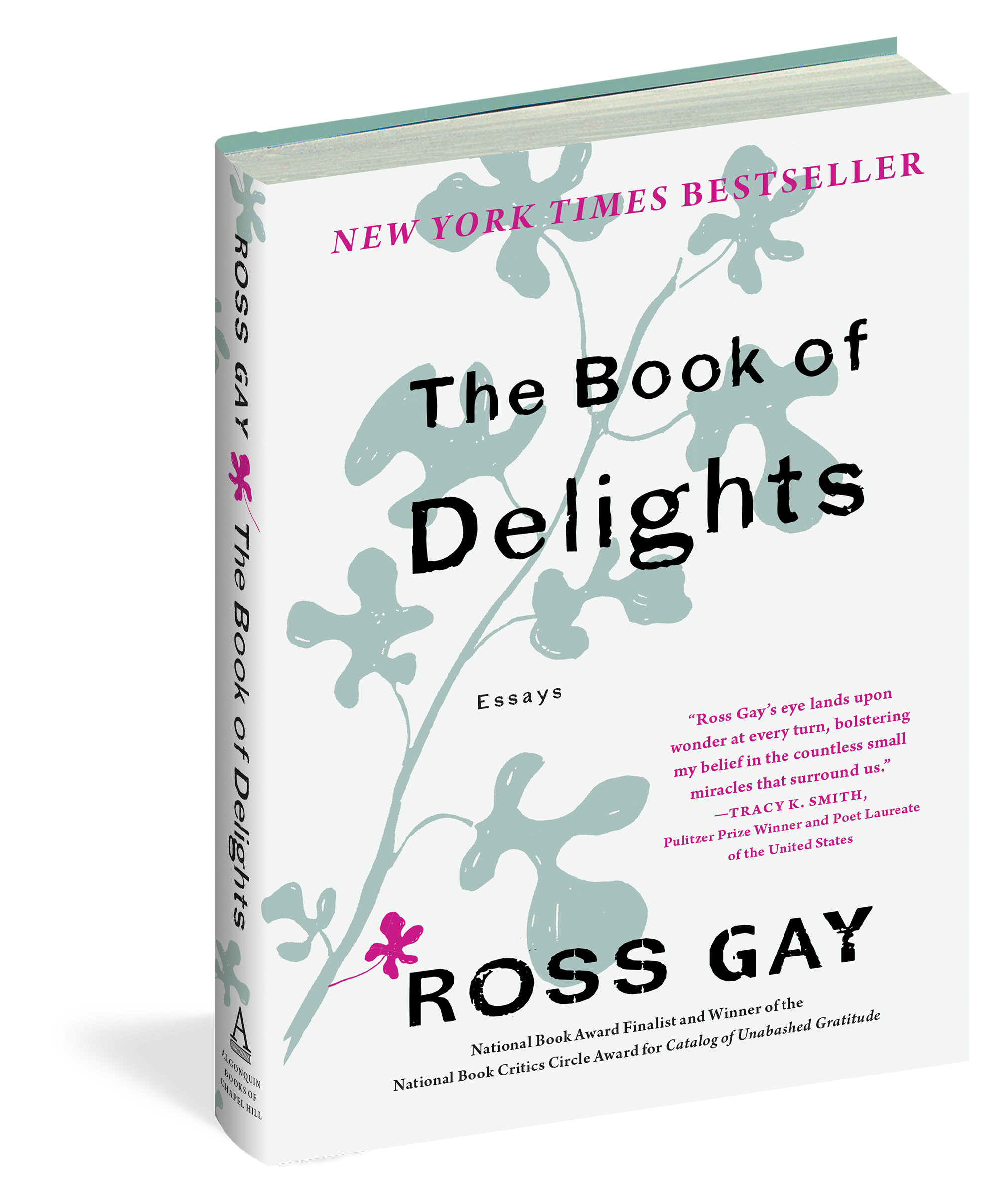

The Book of Delights

Essays

Contributors

By Ross Gay

Formats and Prices

Price

$24.95Price

$30.95 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $24.95 $30.95 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 12, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

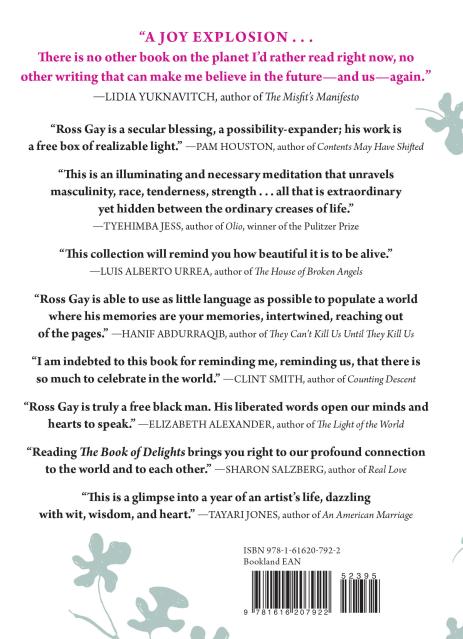

“Ross Gay’s eye lands upon wonder at every turn, bolstering my belief in the countless small miracles that surround us.” —Tracy K. Smith, Pulitzer Prize winner and U.S. Poet Laureate

The winner of the NBCC Award for Poetry offers up a spirited collection of short lyrical essays, written daily over a tumultuous year, reminding us of the purpose and pleasure of praising, extolling, and celebrating ordinary wonders.

In The Book of Delights, one of today’s most original literary voices offers up a genre-defying volume of lyric essays written over one tumultuous year. The first nonfiction book from award-winning poet Ross Gay is a record of the small joys we often overlook in our busy lives. Among Gay’s funny, poetic, philosophical delights: a friend’s unabashed use of air quotes, cradling a tomato seedling aboard an airplane, the silent nod of acknowledgment between the only two black people in a room. But Gay never dismisses the complexities, even the terrors, of living in America as a black man or the ecological and psychic violence of our consumer culture or the loss of those he loves. More than anything else, though, Gay celebrates the beauty of the natural world–his garden, the flowers peeking out of the sidewalk, the hypnotic movements of a praying mantis.

The Book of Delights is about our shared bonds, and the rewards that come from a life closely observed. These remarkable pieces serve as a powerful and necessary reminder that we can, and should, stake out a space in our lives for delight.

Genre:

-

A NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER

As Heard on NPR's This American Life

“The delights he extols here (music, laughter, generosity, poetry, lots of nature) are bulwarks against casual cruelties. As such they feel purposeful and imperative as well as contagious in their joy.”

—The New York Times Book Review

“These charming, digressive ‘essayettes,’ in the manner of Montaigne, surprise and challenge . . . Gay, an award-winning poet, knows the value of formal constraint: his experiences of ‘delight,’ recorded daily for a year, vary widely but yield revealing patterns through insights about everything from nature and the body to race and masculinity. The fruits of this experiment—for which gardens and gardening provide a frequent, apt metaphor—attest to an imagination cultivated in hostile conditions. Gay’s optimism is as easy as it is improbable, his ‘heart cooing like a pigeon nestled on a windowsill where the spikes rusted off.’”

—The New Yorker

"What emerges is not a ledger of delights passively logged but a radiant lens actively searching for and magnifying them, not just with the mind but with the body as an instrument of wonder-stricken presence.”

—Brain Pickings, Favorite Books of 2019

“Ross Gay’s poems are little celebrations of joy, and this book of mini-essays—each centering around a particular 'delight,’ from sleeping in your clothes to planting tomato seedlings to the nod of greeting between the only two black people in a room—is a pure balm for your soul. Savor one at a time every morning, this summer, or wolf them all down en masse on a gorgeous sunny day.”

—Celeste Ng for GoodMorningAmerica.com

"Delightfully snackable . . . Pick it up, read for ten minutes (start anywhere, really), put it down, and you’ll find that the delights of Gay’s world illuminate the delights of yours, that his wonder is contagious and has caused you to deepen your own."

—GQ

“The shock of Gay’s writing . . . is his seamless shift from breezy, affable observation to sober (and admittedly still affable) profundity . . . I want to say that Gay’s writing is magical because that’s the way it feels when I read it. But . . . calling it magic undercuts Gay’s craft, the effort that goes into producing literature that feels as fluent and familiar as a chat with a close friend. His voice has integrity, in both senses of the word: a completeness or consistency, true to itself; and an honesty and compassion so frankly subjective that it produces an incorruptible vision. Gay’s loose-limbed sentences diagram his delight, partaking in numerous asides—some as paragraph-long parentheticals—and equally numerous asides within asides, as well as nested subordinate clauses that are the purview of intimate conversation, not written prose. They are clauses and asides in which, as Gay writes them, you feel his hand on your arm, you feel him lean in toward you, conspiratorially or simply to emphasize his meaning.”

—The New York Review of Books

“Everyone could use a bit more delight in their days . . . Gay, who is the winner of the NBCC Award for Poetry, is here to provide just that, with essays celebrating everything from air quotes to candy wrappers to pickup basketball games.”

—New York Post

“The Book of Delights is both practice and perfection in an unassuming package . . . These pieces reflect and examine the natural world, masculinity, racism, and other topics with vibrancy. Most essays are a few paragraphs, a page or two at maximum, but it’s not the width or length of the pieces that ultimately grabbed my attention. It was the heart and intelligence found within his daily introspections.”

—The Rumpus

"A reminder of what the personal essay is best at: finding the profound in the mundane . . . his delight is infectious. It’s hard to read Gay and not to be won over.”

—Seattle Times

“This collection proves is that delight is infectious and demands to be shared, and, most importantly, ‘our delight grows as we share it.’

—Washington Independent Review of Books

“It's the perfect read to inspire observing your corner of the world with a little more care and delight.”

—NPR.org

“Sweet, powerful, funny, honest, moving. Gay has a new book on the way, too; I can’t wait for it.”

—Orange County Register

- On Sale

- Feb 12, 2019

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Algonquin Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781616207922

ABOUT ROSS GAY

Ross Gay is the author of three books of poetry, including Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude, winner of the 2015 National Book Critics Circle Award and the 2016 Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award. Catalog was also a finalist for the 2015 National Book Award in Poetry, the Ohioana Book Award, the Balcones Poetry Prize, the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award, and was nominated for an NAACP Image Award. He is a founding editor, with Karissa Chen and Patrick Rosal, of the online sports magazine Some Call It Ballin’ and founding board member of the Bloomington Community Orchard, a nonprofit, free-fruit-for-all food justice and joy project. Gay has received fellowships from the Cave Canem Foundation, the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, and the Guggenheim Foundation. He teaches at Indiana University.

See Ross read in person. Check out his event schedule.

PREVIEW OF THE BOOK OF DELIGHTS

“The Marfa Lights”

My buddy Pat and I went to shoot around at the courts here in Marfa today. We were warming up, shooting twelve-footers or doing slow spin moves and crossovers, when a young guy from the other side of the court (where the rim had a net) swaggered toward us, holding a ball on his hip, the light gleaming in his earrings, and challenged us to a two on two, pointing his thumb to himself and back to his buddy draining threes from the corner. We agreed, and went on to kick the shit out of them, 21-0. That is a horrible figure of speech, and I leave it in only to expose the violence we easily speak. We got more baskets than they did. That they were only twelve years old is irrelevant, given as this was their home court, and they even had a crowd watching, another little girl who, when one of the kids shouted to the gods, “They’re kicking our butts!” said, “I hope so. They’re grown men.”

“Tomato on Board”

What you don’t know until you carry a tomato seedling through the airport and onto a plane, is that carrying a tomato seedling through the airport and onto a plane will make people smile at you almost like you’re carrying a baby. A quiet baby. I did not know this until today, carrying my little tomato, about three or four inches high in its four-inch plastic starter pot, which my friend Michael gave to me, smirking about how I was going to get it home. Something about this, at first, felt naughty—not comparing a tomato to a baby, but carrying the tomato onto the plane—and so I slid the thing into my bag while going through security, which made them pull the bag for inspection. When the security guy saw it was a tomato he smiled and said, “I don’t know how to check that. Have a good day.” But I quickly realized that one of its stems (which I almost wrote as “arms”) was broken from the jostling, and it only had four of them, so I decided I better just carry it out in the open. And the shower of love began. . .

Before boarding the final leg of my flight, one of the workers said, “Nice tomato,” which I don’t think was a come on. And the flight attendant asked about the tomato at least five times, not an exaggeration, every time calling it “my tomato,” —Where’s my tomato? How’s my tomato? You didn’t lose my tomato, did you? She even directed me to an open seat in the exit row—Why don’t you guys go sit there and stretch out? I gathered my things and set the lil guy in the window seat so he could look out. When I got my water I poured some into the lil guy’s soil. When we got bumpy I put my hand on the lil guy’s container, careful not to snap another arm off. And when we landed, and the pilot put the brakes on hard, my arm reflexively went across the seat, holding the lil guy in place, the way my dad’s arm would when he had to brake hard in that car without seatbelts to speak of, in one of my very favorite gestures in the encyclopedia of human gestures.

DELIGHT FOR THE BOOK OF DELIGHTS

“Reading The Book of Delights, I’ve tried to limit myself to one “delight” a day. But Ross Gay’s inspirational poetic meditations on the wonder and magic of daily life are too addictive and necessary – I find myself devouring the book and rereading my favorites.”

—ROBERT SINDELAR, Managing Partner of Third Place Books and President of the American Booksellers Association

“Ross Gay’s eye lands upon wonder at every turn, bolstering my belief in the countless small miracles that surround us.”

—TRACY K. SMITH, Pulitzer Prize winner and U.S. Poet Laureate

“Ross Gay’s The Book of Delights reminds us of the wisdom of old songs: What a difference a day makes. This is a glimpse into a year of an artist’s life, dazzling with wit, wisdom and heart.”

—TAYARI JONES, bestselling author of An American Marriage