Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

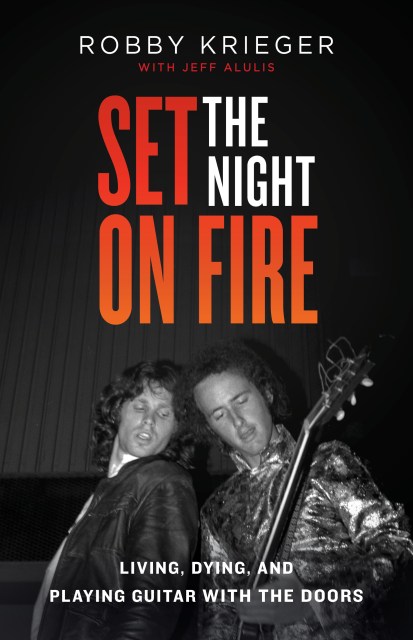

Set the Night on Fire

Living, Dying, and Playing Guitar With the Doors

Contributors

With Jeff Alulis

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 12, 2021

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316243544

Price

$14.99Price

$18.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Digital download $14.99 $18.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 12, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In his tell-all, legendary Doors guitarist, Robby Krieger, one of Rolling Stone's "100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time," opens up about his band's meteoric career, his own darkest moments, and the most famous black eye in rock 'n' roll.

Few bands are as shrouded in the murky haze of rock mythology as The Doors, and parsing fact from fiction has been a virtually impossible task. But now, after fifty years, The Doors' notoriously quiet guitarist is finally breaking his silence to set the record straight.

Through a series of vignettes, Robby Krieger takes readers back to where it all happened: the pawn shop where he bought his first guitar; the jail cell he was tossed into after a teenage drug bust; his parents' living room where his first songwriting sessions with Jim Morrison took place; the empty bars and backyard parties where The Doors played their first awkward gigs; the studios where their iconic songs were recorded; and the many concert venues that erupted into historic riots. Set the Night on Fire is packed with never-before-told stories from The Doors' most vital years, and offers a fresh perspective on the most infamous moments of the band's career.

Krieger also goes into heartbreaking detail about his life's most difficult struggles, ranging from drug addiction to cancer, but he balances out the sorrow with humorous anecdotes about run-ins with unstable fans, famous musicians, and one really angry monk. Set the Night on Fire is at once an insightful time capsule of the '60s counterculture, a moving reflection on what it means to find oneself as a musician, and a touching tale of a life lived non-traditionally. It's not only a must-read for Doors fans, but an essential volume of American pop culture history.

-

“Set the Night on Fire is always warm, often funny, and frequently revelatory…an intimate and honest look inside one of the most compelling outfits in music. It towers above the piles of other Doors documents as a powerful reminder that the truth can be more fascinating than the myth.”People

-

“Doors guitarist Krieger riffs melodiously through the discordant and harmonious measures of his life and times with the band in this galloping, episodic debut.”Publishers Weekly

-

“Krieger [is] just as compelling as a writer as he is with his vast carousel of Gibsons…But besides the treasure trove of new Doors anecdotes in his memoir, the guitarist and singer-songwriter candidly reveals many other personal stories about “living and dying.”Vulture

-

“Set the Night on Fire is the best memoir by a band member of one of the era’s most unique—and mythologized—groups.”Houston Press

-

"Krieger relays untold anecdotes and he's ribaldly funny...Everyone remotely connected to the Doors has written reminiscences of the Lizard Kingdom, but this is one of the very best."MOJO