Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

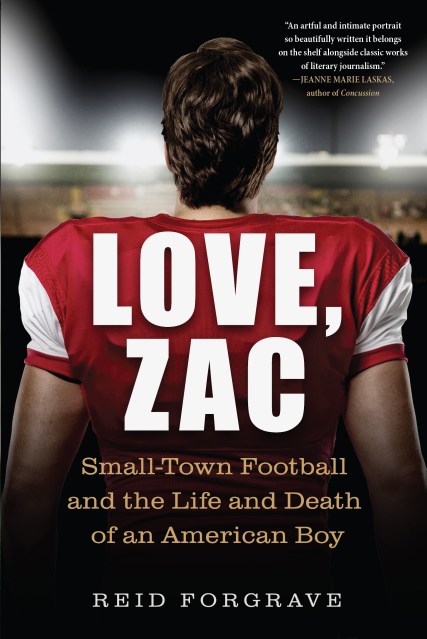

Love, Zac

Small-Town Football and the Life and Death of an American Boy

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.95Price

$22.95 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.95 $22.95 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 7, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

"Love, Zac is not just a vital contribution to the national conversation about traumatic brain injury in athletes, it’s so beautifully written it belongs on the shelf alongside classic works of literary journalism.” —Jeanne Marie Laskas, New York Times bestselling author of Concussion

In December 2015, Zac Easter, a twenty-four-year-old from small-town Iowa, decided to take his own life rather than continue his losing battle against traumatic brain injuries he had sustained as a high school football player and which led him to develop chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). For this deeply reported and powerfully moving true story, award-winning writer Reid Forgrave was given access to Zac’s own diaries and was able to speak with Zac’s family, friends, and coaches. He explores Zac’s tight-knit, football-obsessed Midwestern community; he interviews leading brain scientists, psychologists, and sports historians; he takes a deep dive into the triumphs and sins of the sports entertainment industry; and he shows us the fallout from the traditional notions of manhood that football instills. For parents wondering about whether to allow their kids to play football, for players, former players, and fans, for anyone concerned about concussions and sports, this eye-opening, heart-wrenching, and ultimately inspiring story may be one of the most important books they will read.

Genre:

-

“What an accomplishment. Brimming with compassion and insight, Reid Forgrave has written an artful and intimate portrait of a former high school football star that travels ambitiously into themes of masculinity, suffering, and the nature of a national obsession. Love, Zac is not just a vital contribution to the national conversation about traumatic brain injury in athletes, it’s so beautifully written it belongs on the shelf alongside classic works of literary journalism.”

—Jeanne Marie Laskas, New York Times bestselling author of Concussion

“Sportswriter Forgrave stuns in this moving debut . . . This unflinching exposé is one anyone who loves the sport should pick up.”

—Publishers Weekly

“The concussion epidemic has spread devastation to players in the less visible strata of the sport, especially to high school players like Zac Easter. Love, Zac shows the totality of that damage in full. Someone should staple this book to Roger Goodell’s forehead.”

—Drew Magary, author of The Hike and The Postmortal

“An essential work of sports reporting, Love, Zac explores the dark side of small-town football culture and the warning signs of CTE, interspersed with passages from Zac’s diary and interviews with his family and friends.”

—New York Post

“An intelligent, provocative tale that will give pause to many parents of football players at any level.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“A tragic, moving story that will linger with readers of sports and biographies in general.”

—Library Journal

“A heartbreaking biography [that] underscores the moral ambiguity of supporting life-threatening sports.”

—Shelf Awareness

“A monumental achievement of deep reporting and expert storytelling. One question echoes from every page of this book: What happened to Zac Easter? In seeking the answers, Reid Forgrave has written a detective story, a love story, and a parable about football, pain and the consequences of the bedrock version of American masculinity.”

—Michael Sokolove, author of The Last Temptation of Rick Pitino and Drama High

“An in-depth exploration not only of football and its risks, but of the empty-calorie culture into which we are driving young men. It will leave you unable to ever watch a football game—at any level—the same way again.”

—Brian Alexander, author of Glass House

- On Sale

- Sep 7, 2021

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Algonquin Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781643752020

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use