Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

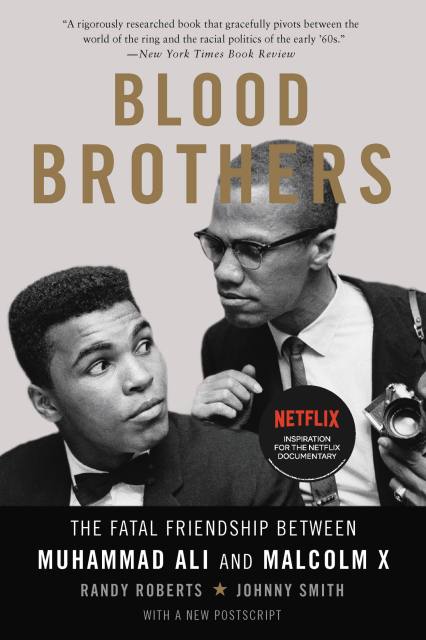

Blood Brothers

The Fatal Friendship Between Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X

Contributors

By Johnny Smith

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 1, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

An “engrossing and important book" (Wall Street Journal) that brings to life the fateful friendship between Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali

In 1962, boxing writers and fans considered Cassius Clay an obnoxious self-promoter, and few believed that he would become the heavyweight champion of the world. But Malcolm X, the most famous minister in the Nation of Islam, saw the potential in Clay, not just for boxing greatness, but as a means of spreading the Nation’s message. The two became fast friends, keeping their interactions secret from the press for fear of jeopardizing Clay’s career. Clay began living a double life—a patriotic “good negro” in public, and a radical reformer behind the scenes. Soon, however, their friendship would sour, with disastrous and far-reaching consequences.

Based on previously untapped sources, from Malcolm’s personal papers to FBI records, Blood Brothers is the first book to offer an in-depth portrait of this complex bond. An extraordinary narrative of love and deep affection, as well as deceit, betrayal, and violence, this story is a window into the public and private lives of two of our greatest national icons, and the tumultuous period in American history that they helped to shape.

- On Sale

- Nov 1, 2016

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465093236

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use