Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

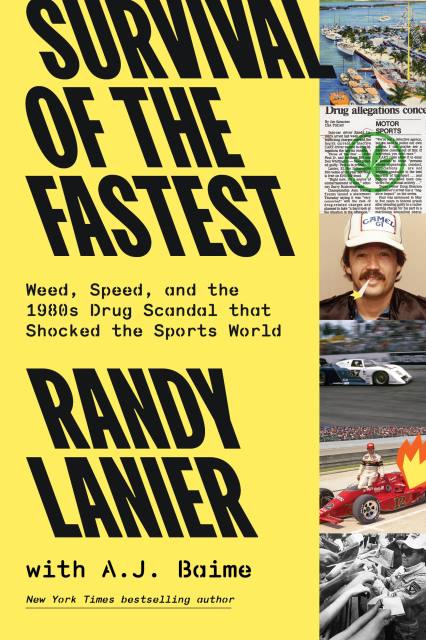

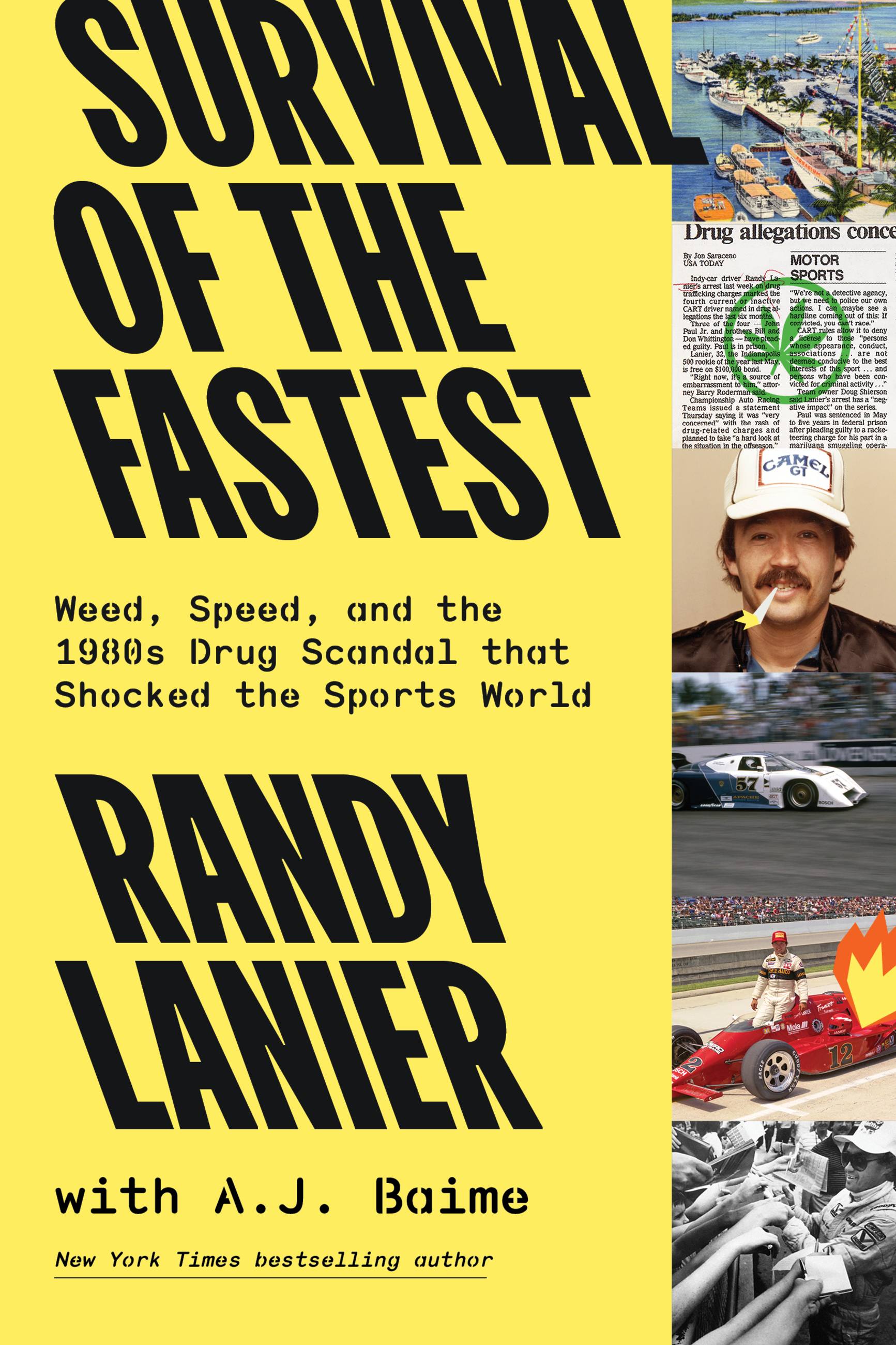

Survival of the Fastest

Weed, Speed, and the 1980s Drug Scandal that Shocked the Sports World

Contributors

By Randy Lanier

With A.J. Baime

Formats and Prices

Price

$29.00Price

$37.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 2, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

**Winner of the Best Book Award by the Motor Press Guild**

The high-octane, Seabiscuit-meets-Scarface story of how Randy Lanier became a 1980s international sports star, soaring through the ranks of car racing while holding a dark secret: he was also one of the biggest pot smugglers in American history

As a kid, Randy Lanier dreamed of achieving four-wheel glory at the Indianapolis 500, but knew he’d never be able to afford the most expensive sport on earth. That all changed when he bought a speedboat and began smuggling pot from the Bahamas. Fueled by what would become a historically massive smuggling operation, he started racing cars and became an overnight sensation. For Randy and his teammates, money was no object, and bigger hauls meant faster cars. At every event they attended, they were behind the wheel of the best machinery, flaunting their secret in front of huge crowds and live television cameras. But no matter how fast they drove, they couldn’t outrun the law. As Randy came ever closer to reaching his dream of high-speed glory, one of the biggest drug scandals ever to hit the professional sports world was about to unfold.

Set in the 1980s Florida of Miami Vice, this is the unbelievable, unforgettable, unparalleled story of an ordinary guy whose attempts to become famous doing the thing he wanted most—become a world class race car driver—devolved into a you-can’t-make-this-up tale of one of the biggest crime rings and drug scandals of the 1980s. Now, with the help of New York Times bestselling author A.J. Baime, Randy tells the whole truth for the first time ever, a gripping narrative unlike any other, a sports story for the ages, and shocking a true crime epic.

Genre:

-

“Flooring his racer on the back straight of the Indy 500 at the same time that his barge with 80 tons of pot bucks up waves along the California coast, Randy Lanier didn't let me go until the last page of his ripping, true saga.”Bruce Porter, New York Times bestselling author of Blow: How a Small-Town Boy Made $100 Million with the Medellín Cocaine Cartel and Lost It All

-

"Like any self-respecting outlaw, Lanier has a hell of a time breaking the law, even as knuckleheaded hubris promises ruination, but you can't help but cheer for him as the glory and despair of the checkered flag of his rookie Indy 500 finish line and clanging prison doors loom on the horizon."Guy Lawson, New York Times bestselling author of War Dogs: How Three Stoners from Miami Beach Became the Most Unlikely Gunrunners in History

-

“Tell me you're not going to read this whopper of a true-life tale. Buckle your seat belts. This is one terrific ride.”Leigh Montville, New York Times bestselling author of The Big Bam

-

"As the test pilot for the world's most dangerous amusement park, I was thrust right back into those harrowing days as I read the story of Randy Lanier and his wild ride of a life from drug smuggler to race car driver. It’s non-stop action and a thrill a minute. Strap in and blast off!"Andy Mulvihill, Author of Action Park: Fast Times, Wild Rides, and the Untold Story of America’s Most Dangerous Amusement Park

-

“A great read, equal parts true crime, business story, and Shakespearean tragedy as Lanier’s compulsion to learn how good he could be on the track led him to clandestine offshore meetings, Swiss banks and the jungles of Colombia….It reads like a carefully researched novel, packed with confrontations, incredibly detailed capers and hair’s-breadth escapes….From its peaks to devastating lows, Lanier’s story is an enthralling tale of love, dreams, a family torn apart, devastation and redemption.”Detroit Free Press

-

“Survival of the Fastest is the motorsport and marijuana-smuggling story you've been waiting for. You already knew Randy Lanier's life was unbelievable. You probably just didn't know how unbelievable – until now….this book is a stellar one….The mark of a great book is its ability to reel you in and never let you go, and Survival of the Fastest does exactly that….without a doubt, one of the most incredible motorsport books I’ve ever read.”Jalopnik

- On Sale

- Aug 2, 2022

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780306826450

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use