Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

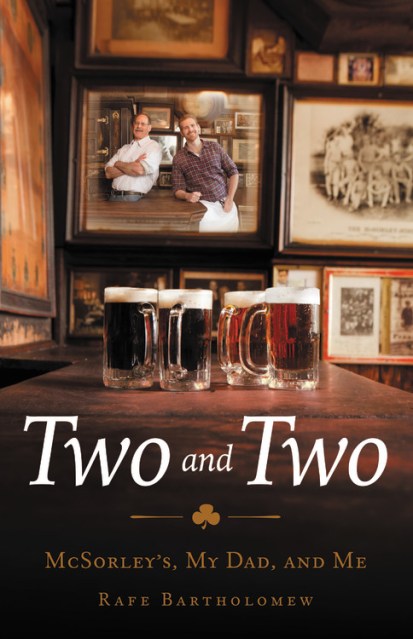

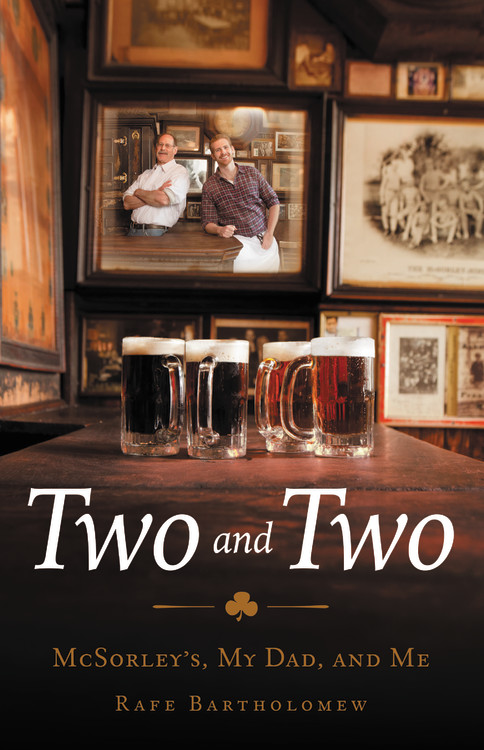

Two and Two

McSorley's, My Dad, and Me

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$27.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $27.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.49 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 9, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Since it opened in 1854, McSorley’s Old Ale House has been a New York institution. This is the landmark watering hole where Abraham Lincoln campaigned and Boss Tweed kicked back with the Tammany Hall machine. Where a pair of Houdini’s handcuffs found their final resting place. And where soldiers left behind wishbones before departing for the First World War, never to return and collect them. Many of the bar’s traditions remain intact, from the newspaper-covered walls to the plates of cheese and raw onions, the sawdust-strewn floors to the tall-tales told by its bartenders.

But in addition to the bar’s rich history, McSorley’s is home to a deeply personal story about two men: Rafe Bartholomew, the writer who grew up in the landmark pub, and his father, Geoffrey “Bart” Bartholomew, a career bartender who has been working the taps for forty-five years.

On weekends, Rafe Bartholomew would tag along for the early hours of his dad’s shift, polishing brass doorknobs, watching over the bar cats, and handling other odd jobs until he grew old enough to join Bart behind the bar. McSorley’s was a place of bizarre rituals, bawdy humor, and tasks as unique as the bar itself: protecting the decades-old dust that had gathered on treasured artifacts; shot-putting thirty-pound grease traps into high-walled Dumpsters; and trying to keep McSorley’s open through the worst of Hurricane Sandy.

But for Rafe, the bar means home. It’s the place where he and his father have worked side by side, serving light and dark ale, always in pairs, the way it’s always been done. Where they’ve celebrated victories, like the publication of his father’s first book of poetry, and coped with misfortune, like the death of Rafe’s mother. Where Rafe learned to be part of something bigger than himself and also how to be his own man. By turns touching, crude, and wildly funny, Rafe’s story reveals universal truths about family, loss, and the bursting history of one of New York’s most beloved institutions.

Genre:

-

Praise for Two and TwoJames McBride, author of The Color of Water and The Good Lord Bird

"This is more than a story about a famous speakeasy where, for the price of a beer, you can still sit at the same tables where great writers like Joseph Mitchell, Eugene O'Neill, and e.e. Cummings once sat and ruminated. This is a story about a father and son, both of whom toiled for years amidst the ghosts a hundred years past, when a group of hard working Irish Americans created one of New York's greatest institutions with nothing more than sweat, beer, liverwurst sandwiches, and an occasional punch in the nose to all spoilers and bullies.

"Many a day I have sat in McSorley's amidst the sawdust and beer and said to myself, 'You'd have to be a child of this place to make these ghosts speak.' And that is exactly what Rafe Bartholomew is. His is the voice of ages, the shouts of thousands of fireman, cops, soldiers, drunks, bums, wayfarers, liars, and good souls whose hard luck brought them to McSorley's, and whose good spirit still reign over the place. He hoists this wonderful piece of Americana into the air with all the humor, joy, humility and love that it deserves." -

"Rafe Bartholomew has written a smart, moving book for the inner New Yorker (and inner barfly) in all of us. His father-not to mention Old John McSorley himself-should be damned proud."Tom Bissell, author of Apostle and Extra Lives

-

"In Two and Two, Rafe Bartholomew has not just lovingly crafted an homage to a singular American place of drink, but also given us a steady look into the intense realm of father and son. This memoir pulses with uncommon talent."William Giraldi, author of The Hero's Body and Hold the Dark

-

"Rafe's like a brother to me. So to read this book is to discover a childhood I never knew he had (never knew any kid could have!) and a dad I can't wait to meet. Rafe presents both with enviable, high-definition affection. This is a biography of a father and the bar that became part of his soul. It's a memoir of a son the bar co-parented. It's history of New York City and a sly, considered essay on masculinity. It's a book quietly about a mythic America that simultaneously never really existed yet, obviously, totally did. Rafe's writing, his memories, his sensitivity and sweetness made me laugh. They moved me. In my years living in New York, I never thought of a bar like McSorley's as a bar for me. The hefty beauty and lasting surprise of this book is how it reminds me over and over that I was probably - maybe certainly - wrong."Wesley Morris, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Criticism

-

"Quite simply the best thing I've read about fathers and sons (Turgenev, eat your heart out)."Lawrence Block, New York Times bestselling author

-

A "big-hearted memoir of a lifelong romance with New York City's oldest (continuously operating) saloon... a watering hole for artists, politicians, and oddballs, a storehouse of oral tradition passed through generations of staff... [Bartholomew's] portrayal of the rough humor and blue-collar warmth feels completely earned."Publishers Weekly

-

"There is no bar in New York City--perhaps even all of America--with as much history as McSorley's Old Ale House.... but for former Grantland editor Bartholomew, McSorley's was just home... The author expertly weaves together entertaining stories from his nights behind the bar... with more poignant moments between father and son.... Bartholomew does both his father and McSorley's proud with this touching, redolent memoir."Kirkus

-

"McSorley's Old Ale House had been a Manhattan legend for more than 100 years when the author's father was hired on to work the taps. ....The nostalgia-drenched memoir makes us want to revisit the joint."Booklist

-

"Few bars in America are as storied as New York's McSorley's Old Ale House, which dates back to 1854. No matter if you've had the pleasure of enjoying a pint of its signature dark beer or not, you'll enjoy Rafe Bartholomew's memoir of his experience working at the establishment alongside his father."Noah Rothbaum, The Daily Beast

-

For "anyone interested in the city, beer, or the infinitely mutable ideal of 'Old New York.'"Thrillist

-

"A love letter to McSorley's most idiosyncratic conventions"Grub Street

-

"Charming... will make you immediately thirst for a few mugs of its beer and inspire a sojourn to the legendary Big Apple monument."The Daily Beast

-

"The bar's incomparable atmosphere is difficult to capture, but in his new book, Two and Two, Rafe Bartholomew does just that, providing a vivid history of the bar and a firsthand account of working there....A 'touching, redolent memoir' that should appeal to barflies and NYC historians alike."Eric Liebetrau, Kirkus Reviews

-

"McSorley's is a storied bar, but its stories have rarely been this well told....In Bartholomew's book he reminds us of [McSorley's] greatness, and in a real sense, our own."Cahir O'Doherty, Irish Central

-

"An unabashedly sentimental--yet realistic--look at the father-son relationship"BookPage

-

"Rafe's relationship with McSorley's is deeply personal and effectively illustrative of the true nature of fatherhood and the importance of familial traditions... [McSorley's] shaped his identity and appreciate for the tradition of storytelling."Christina Troitino, Forbes

- On Sale

- May 9, 2017

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316231596

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use