Promotion

Use code FALL24 for 20% off sitewide!

How to Sleep

The New Science-Based Solutions for Sleeping Through the Night

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$24.95Price

$31.95 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $24.95 $31.95 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $18.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 8, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

“Easy to read and comprehensive. This book offers real practical guidance.”

—Matthew Walker, PhD, bestselling author of Why We Sleep

A MindBodyGreen Health & Well-Being Book for Your 2021 Reading List

Anyone having trouble sleeping has heard all the old “sleep hygiene” rules: Don’t drink caffeine after 2:00 p.m., use the bedroom only for sleeping, put down your screens an hour before going to bed. But as the millions suffering from poor sleep can attest, just following these overly simplistic, one-size-fits-all directives doesn’t work. How to Sleep is here to rewrite the rules and help you get to sleep—and stay asleep—each and every night.

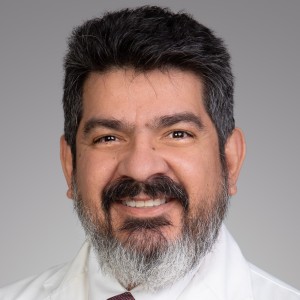

Dr. Rafael Pelayo, an expert sleep clinician and professor at the world-renowned Sleep Medicine Clinic at Stanford University, offers a medically comprehensive and holistic approach to the myriad issues that might be affecting your sleep. He begins by grounding us in the biology of sleep including the extremely reassuring fact that no one actually sleeps through the night—we naturally wake up every ninety minutes. Dr. Pelayo then tackles the major sleep issues one by one, such as snoring and its causes; the difference between transient and chronic insomnia, and how to treat each; strategies to combat jet lag; how lifestyle choices affect your sleep, including exercise (even ten minutes helps), meditation (try it right before bed), and food and drink (alcohol is a double-edged sword—it may help you fall asleep faster, but it often interferes with staying asleep).

There’s advice for the bedroom—on white noise machines, ambient temperature, what to look for in a pillow—and answers to our most pressing questions, from when to see a sleep medicine specialist to how aging affects our sleep. All in all, it’s a sure prescription to help you sleep better, wake up refreshed, and live a healthier life.

-

“How to Sleep rewrites the ‘rules’ of sleep for consumers who realize that sleep hygiene isn’t enough. The book goes far beyond sleep hygiene and tackles issues such as the causes of snoring, treating transient and chronic insomnia, combating jet lag, and how lifestyle choices impact sleep.”

—Sleep Review

“Easy to read and comprehensive. This book offers real practical guidance.”

—Matthew Walker, PhD, bestselling author of Why We Sleep

“This concise but comprehensive book covers all the aspects of normal and abnormal sleep with which we should be familiar. Everyone should read this book.”

—William C. Dement, M.D., Ph.D, bestselling author of The Promise of Sleep

“Want to learn how to optimize your sleep? You’re unlikely to find a clearer or more up-to-date guide than this book by Dr. Pelayo.”

—David Eagleman, neuroscientist, New York Times bestselling author, and creator and host of PBS’s The Brain

“Before reading this book, I thought of myself as a sleep aficionado, but Dr. Pelayo showed me just how many misconceptions I had. How to Sleep taught me that snoring is never normal, about the seriousness and pervasiveness of sleep apnea, and much more. These misunderstandings affect us all—this comforting and confidence-building book should be mandatory reading.”

—Ed Catmull, cofounder of Pixar and author of Creativity, Inc.

“Dr. Pelayo cleverly and thoroughly explains the biology of sleep and strategies we can all use to improve our quality of life and maintain optimal health through better sleep.”

—Richard K. Bogan, MD, chairman of the National Sleep Foundation

“Dr. Pelayo has condensed his vast knowledge and years of experience into a quick, interesting, and captivating must-read book. He offers guidance on sleeping well, the causes of sleep disturbance (including sleep disorders, diet, and medicine), and managing sleep issues in both adults and children.”

—Kannan Ramar, MD, sleep medicine specialist at the Mayo Clinic

- On Sale

- Dec 8, 2020

- Page Count

- 160 pages

- Publisher

- Artisan

- ISBN-13

- 9781579659578

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use