Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

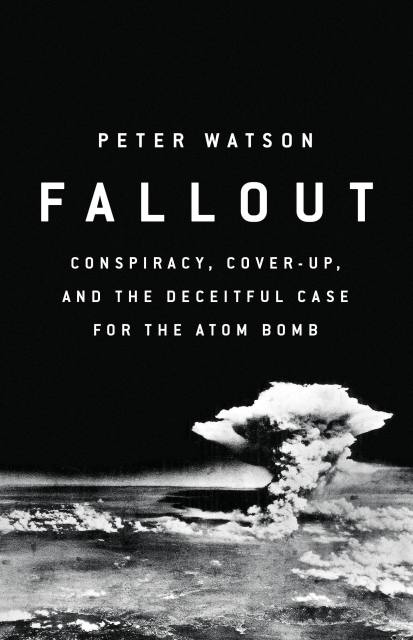

Fallout

Conspiracy, Cover-Up, and the Deceitful Case for the Atom Bomb

Contributors

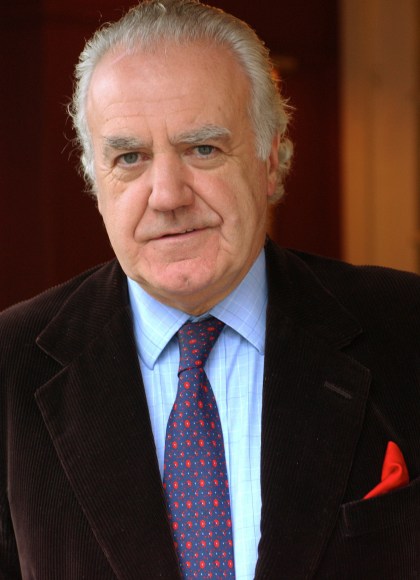

By Peter Watson

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $39.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 18, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Fallout dismantles the conventional story of why the atom bomb was built. Peter Watson has found new documents showing that long before the Allied bomb was operational, it was clear that Germany had no atomic weapons of its own and was not likely to. The British knew this, but didn’t share their knowledge with the Americans, who in turn deceived the British about the extent to which the Soviets had penetrated their plans to build and deploy the bomb.

The dark secret was that the bomb was dropped not to decisively end the war in the Pacific but to warn off Stalin’s Russia, still in principle a military ally of the US and Britain. It did not bring a hot war to an abrupt end; instead it set up the terms for a Cold one to begin.

Moreover, none of the scientists recruited to build the bomb had any idea that the purpose of the bomb had been secretly changed and that Russian deterrence was its new objective.

Fallout vividly reveals the story of the unnecessary building of the atomic bomb, the most destructive weapon in the world, and the long-term consequences that are still playing out to this day.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 18, 2018

- Page Count

- 448 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610399623

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use