Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

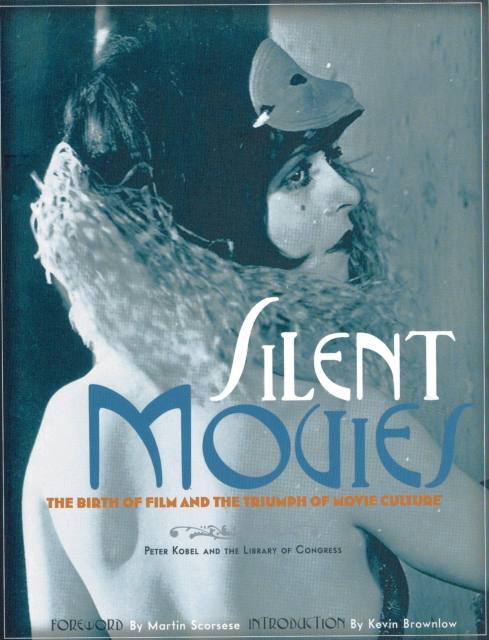

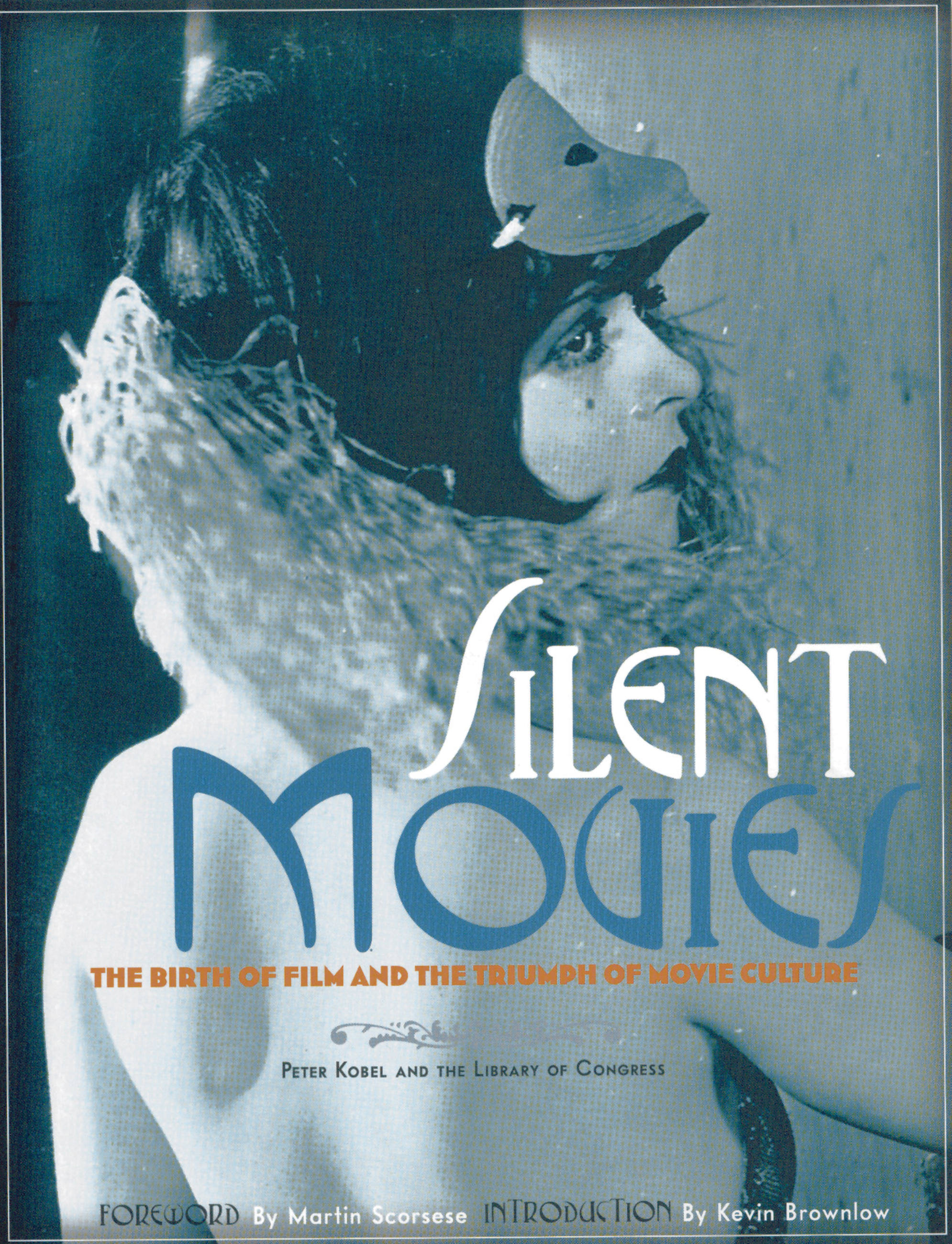

Silent Movies

The Birth of Film and the Triumph of Movie Culture

Contributors

By Peter Kobel

Preface by Martin Scorsese

Foreword by Kevin Brownlow

Formats and Prices

Price

$19.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $19.99 $24.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 28, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Drawing on the extraordinary collection of The Library of Congress, one of the greatest repositories for silent film and memorabilia, Peter Kobel has created the definitive visual history of silent film. From its birth in the 1890s, with the earliest narrative shorts, through the brilliant full-length features of the 1920s, Silent Movies captures the greatest directors and actors and their immortal films.

Silent Movies also looks at the technology of early film, the use of color photography, and the restoration work being spearheaded by some of Hollywood’s most important directors, such as Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola.

Richly illustrated from the Library of Congress’s extensive collection of posters, paper prints, film stills, and memorabilia — most of which have never been in print — Silent Movies is an important work of history that will also be a sought-after gift book for all lovers of film.

Silent Movies also looks at the technology of early film, the use of color photography, and the restoration work being spearheaded by some of Hollywood’s most important directors, such as Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola.

Richly illustrated from the Library of Congress’s extensive collection of posters, paper prints, film stills, and memorabilia — most of which have never been in print — Silent Movies is an important work of history that will also be a sought-after gift book for all lovers of film.

- On Sale

- Feb 28, 2009

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316069595

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use