Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

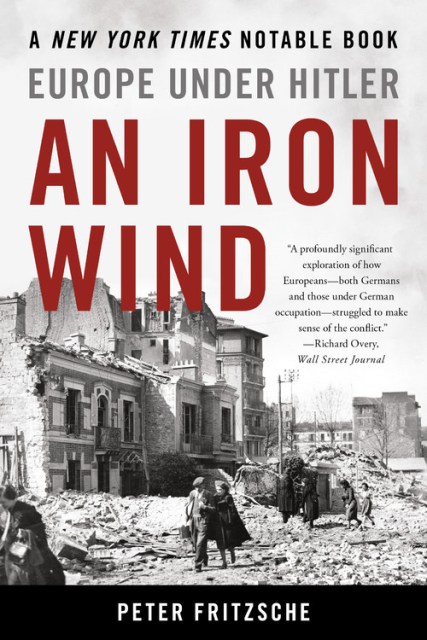

An Iron Wind

Europe Under Hitler

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 3, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A vivid account of German-occupied Europe during World War II that reveals civilians’ struggle to understand the terrifying chaos of war

In An Iron Wind, prize-winning historian Peter Fritzsche draws diaries, letters, and other first-person accounts to show how civilians in occupied Europe tried to make sense of World War II. As the Third Reich targeted Europe’s Jews for deportation and death, confusion and mistrust reigned. What were Hitler’s aims? Did Germany’s rapid early victories mark the start of an enduring new era? Was collaboration or resistance the wisest response to occupation? How far should solidarity and empathy extend? And where was God? People desperately tried to understand the horrors around them, but the stories they told themselves often justified a selfish indifference to their neighbors’ fates.

Piecing together the broken words of the war’s witnesses and victims, Fritzsche offers a haunting picture of the most violent conflict in modern history.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Apr 3, 2018

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541698826

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use