Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

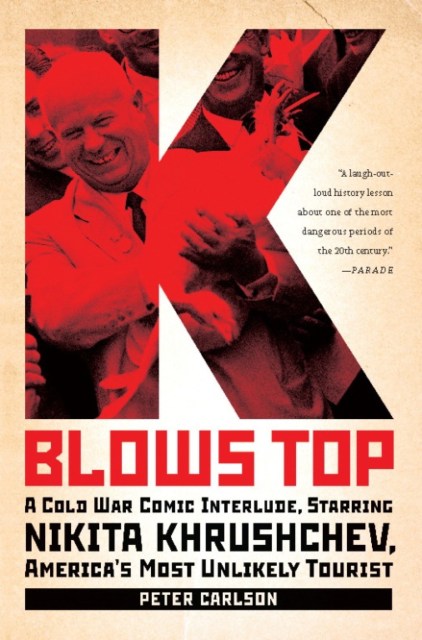

K Blows Top

A Cold War Comic Interlude Starring Nikita Khrushchev, America's Most Unlikely Tourist

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 2, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

K Blows Top is a work of history that reads like a Vonnegut novel. This cantankerous communist’s road trip took place against the backdrop of the fifties in America, with the shadow of the hydrogen bomb hanging over his visit like the Sword of Damocles. As Khrushchev kept reminding people, he was a hot-tempered man who possessed the power to incinerate America.

Genre:

-

Douglas Brinkley, Professor of History and Baker Institute Fellow at Rice University

"What a joy it was to read Peter Carlson's K Blows Top. With vivid detail, crisp language, subtle wit, and admirable new research, Carlson recounts Khrushchev's notorious bungling around America in 1959. A truly fine piece of writing and Cold War scholarship."Christopher Buckley, author of Thank You for Smoking and Supreme Courtship

“Peter Carlson's K Blows Top is an utterly hilarious and un-putdown-able story about one of the strangest episodes of the Cold War -- Khrushchev's 1959 visit to the U.S. Someone absolutely has to make this into a movie. I insist!”The Daily Beast, from Christopher Buckley, author of Thank you for Smoking and

- On Sale

- Jun 2, 2009

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9780786741564

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use