By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

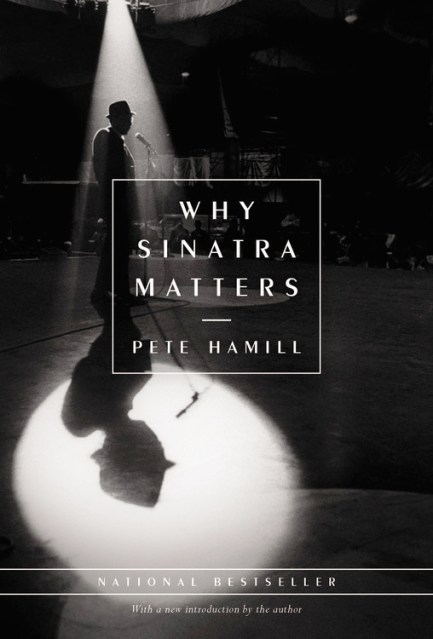

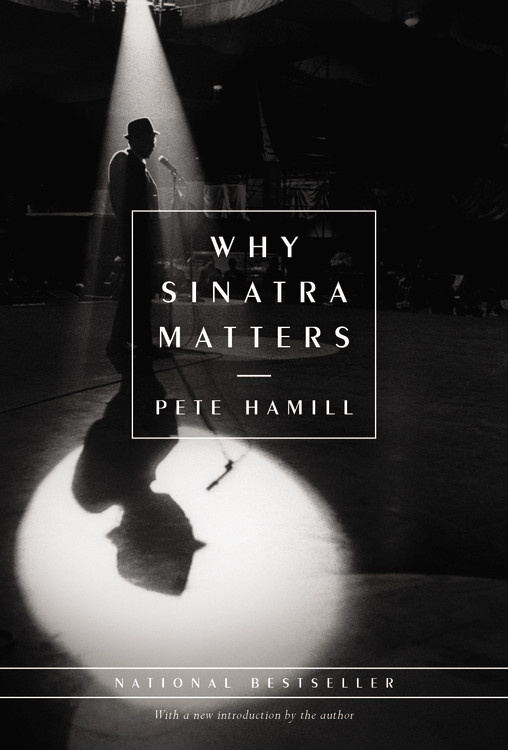

Why Sinatra Matters

Contributors

By Pete Hamill

Formats and Prices

Price

$27.00Price

$34.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $27.00 $34.00 CAD

- ebook $5.99 $7.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 20, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In honor of Sinatra’s 100th birthday, Pete Hamill’s classic tribute returns with a new introduction by the author.

In this unique homage to an American icon, journalist and award-winning author Pete Hamill evokes the essence of Sinatra–examining his art and his legend from the inside, as only a friend of many years could do. Shaped by Prohibition, the Depression, and war, Francis Albert Sinatra became the troubadour of urban loneliness. With his songs, he enabled millions of others to tell their own stories, providing an entire generation with a sense of tradition and pride belonging distinctly to them.

With a new look and a new introduction by Hamill, this is a rich and touching portrait that lingers like a beautiful song.

In this unique homage to an American icon, journalist and award-winning author Pete Hamill evokes the essence of Sinatra–examining his art and his legend from the inside, as only a friend of many years could do. Shaped by Prohibition, the Depression, and war, Francis Albert Sinatra became the troubadour of urban loneliness. With his songs, he enabled millions of others to tell their own stories, providing an entire generation with a sense of tradition and pride belonging distinctly to them.

With a new look and a new introduction by Hamill, this is a rich and touching portrait that lingers like a beautiful song.

-

"The most intimate and thoughtful eulogy for 'the Voice'....It leaves you wanting to listen again to Sinatra's best songs."Entertainment Weekly

-

"As succinct and laconically classy as its title."Adam Woog, Seattle Times

-

"Hamill's illuminations are considerable without ever stooping to facile psychologizing....He does a better job of placing Sinatra's saga in a social and political context than any of his biographers have....Why Sinatra Matters is most valuable in its explication of how Sinatra came to formulate a musical style that was a sound track to urban American life."Dan DeLuca, Philadelphia Inquirer

-

"A graceful reminiscence of Sinatra after hours serves as the frame for shrewd reflections on the singer's art, his personality, his audience, and--most interesting--his ethnicity, a subject about which Hamill, against all odds, contrives to say fresh and persuasive things."Terry Teachout, New York Times Book Review

-

"A brief but eloquent homage....Hamill succeeds--convincingly, with natty aplomb--in explaining why Sinatra, even now, matters."Tom Chaffin, LA Weekly

- On Sale

- Oct 20, 2015

- Page Count

- 208 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316347174

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use