Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

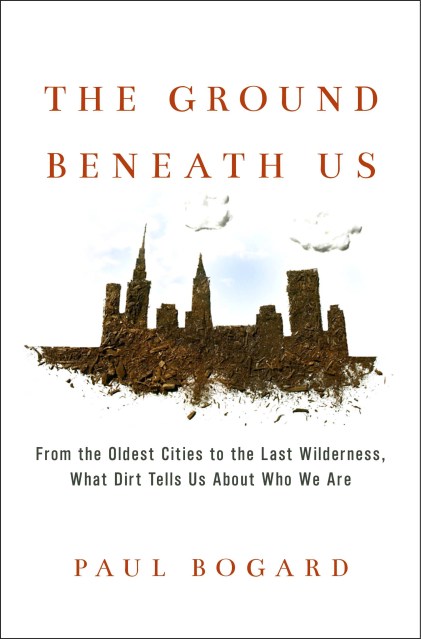

The Ground Beneath Us

From the Oldest Cities to the Last Wilderness, What Dirt Tells Us About Who We Are

Contributors

By Paul Bogard

Formats and Prices

Price

$27.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $27.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 21, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Paul Bogard set out to answer these questions in The Ground Beneath Us, and what he discovered is astounding. From New York (where more than 118,000,000 tons of human development rest on top of Manhattan Island) to Mexico City (which sinks inches each year into the Aztec ruins beneath it), Bogard shows us the weight of our cities’ footprints. And as we see hallowed ground coughing up bullets at a Civil War battlefield; long-hidden remains emerging from below the sites of concentration camps; the dangerous, alluring power of fracking; the fragility of the giant redwoods, our planet’s oldest living things; the surprises hidden under a Major League ballpark’s grass; and the sublime beauty of our few remaining wildest places, one truth becomes blazingly clear: The ground is the easiest resource to forget, and the last we should.

Bogard’s The Ground Beneath Us is deeply transporting reading that introduces farmers, geologists, ecologists, cartographers, and others in a quest to understand the importance of something too many of us take for granted: dirt. From growth and life to death and loss, and from the subsurface technologies that run our cities to the dwindling number of idyllic Edens that remain, this is the fascinating story of the ground beneath our feet.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Mar 21, 2017

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316342261

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use