Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

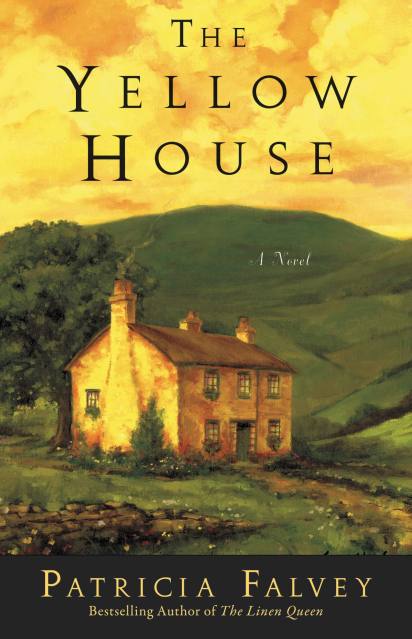

The Yellow House

A Novel

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Prices

- Sale Price $2.99

- Regular Price $9.99

- Discount (70% off)

Prices

- Sale Price $2.99 CAD

- Regular Price $12.99 CAD

- Discount (77% off)

Format

Format:

- ebook $2.99 $2.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 15, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A Northern Irish woman’s life is tangled in political and personal turmoil as she struggles to hold her family together and follow her heart.

She is soon torn between two men, each drawing her to one extreme. One is a charismatic and passionate political activist determined to win Irish independence from Great Britain at any cost, who appeals to her warrior’s soul. The other is the wealthy and handsome black sheep of the pacifist family who owns the mill where she works, and whose persistent attention becomes impossible for her to ignore.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Feb 15, 2010

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Center Street

- ISBN-13

- 9781599952673

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use