By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

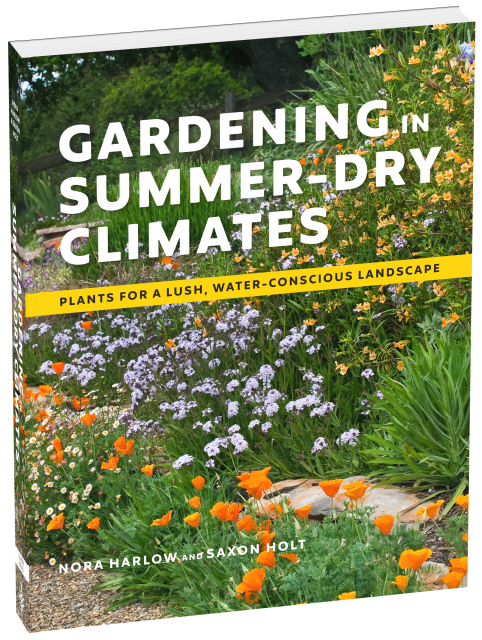

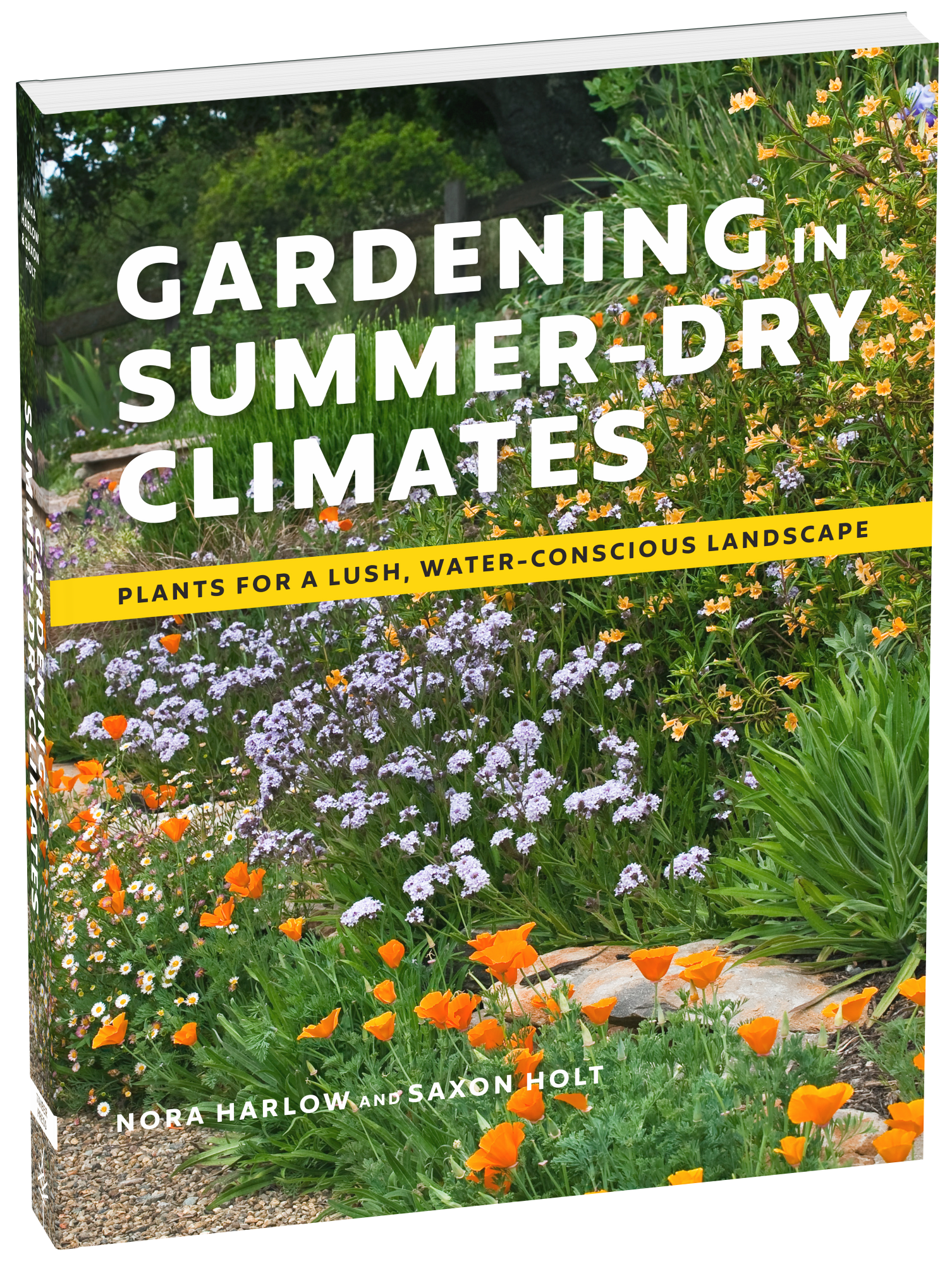

Gardening in Summer-Dry Climates

Plants for a Lush, Water-Conscious Landscape

Contributors

By Nora Harlow

By Saxon Holt

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jan 5, 2021

- Page Count

- 308 pages

- Publisher

- Timber Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781604699128

Price

$29.95Price

$37.95 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $29.95 $37.95 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 5, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

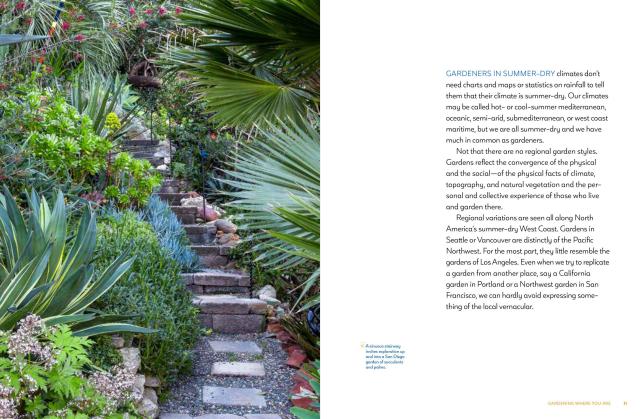

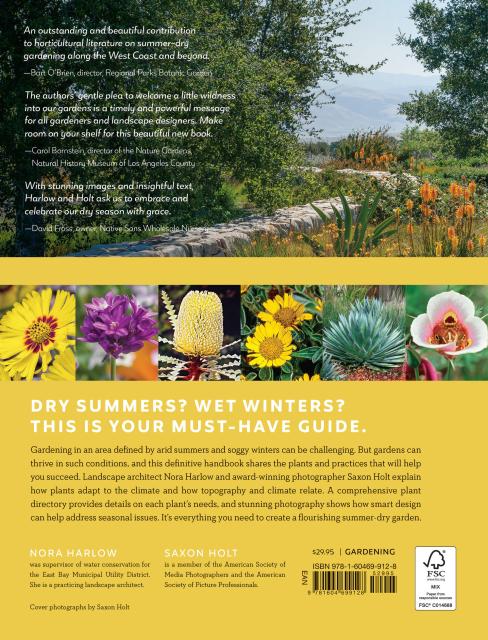

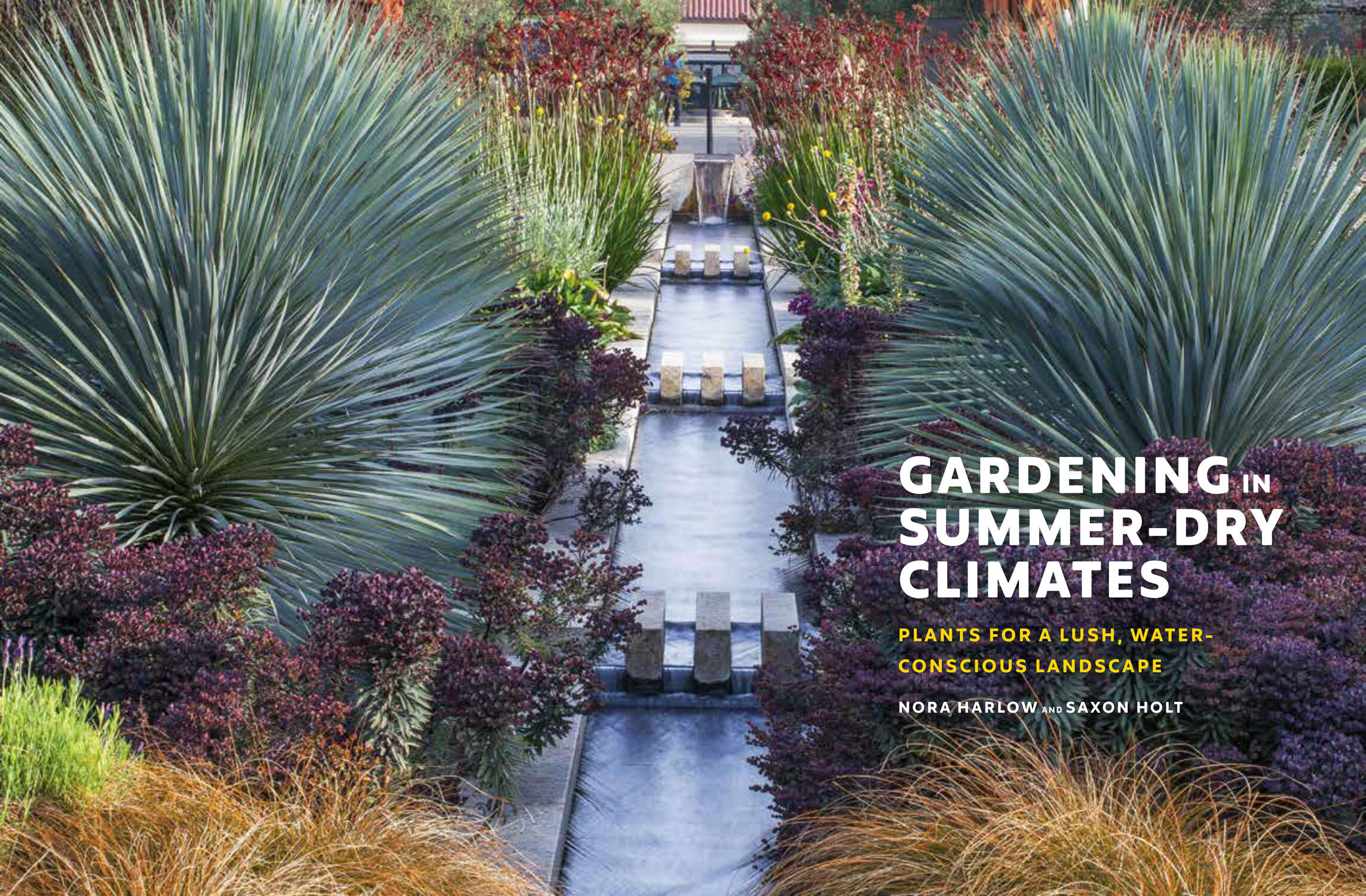

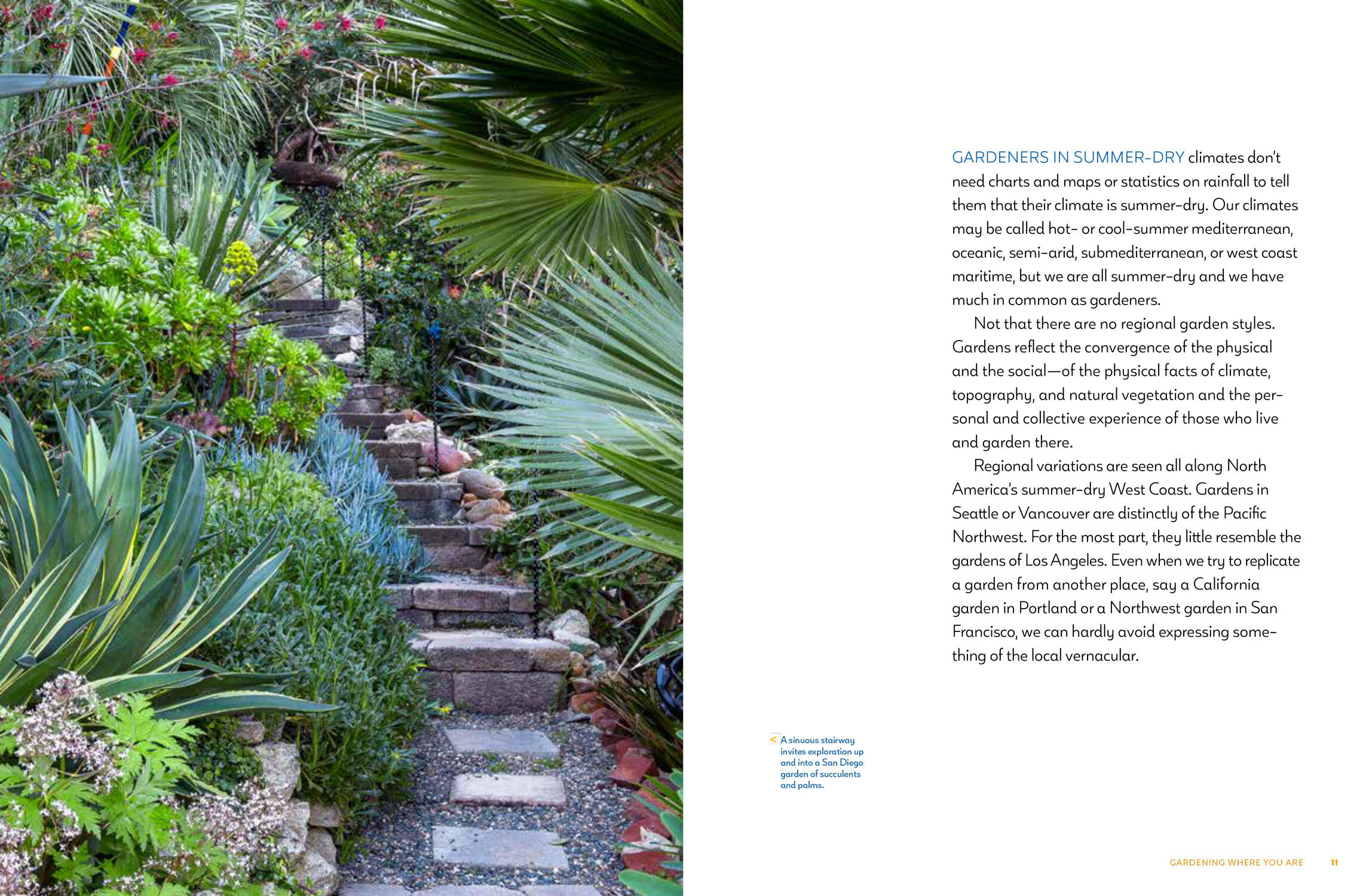

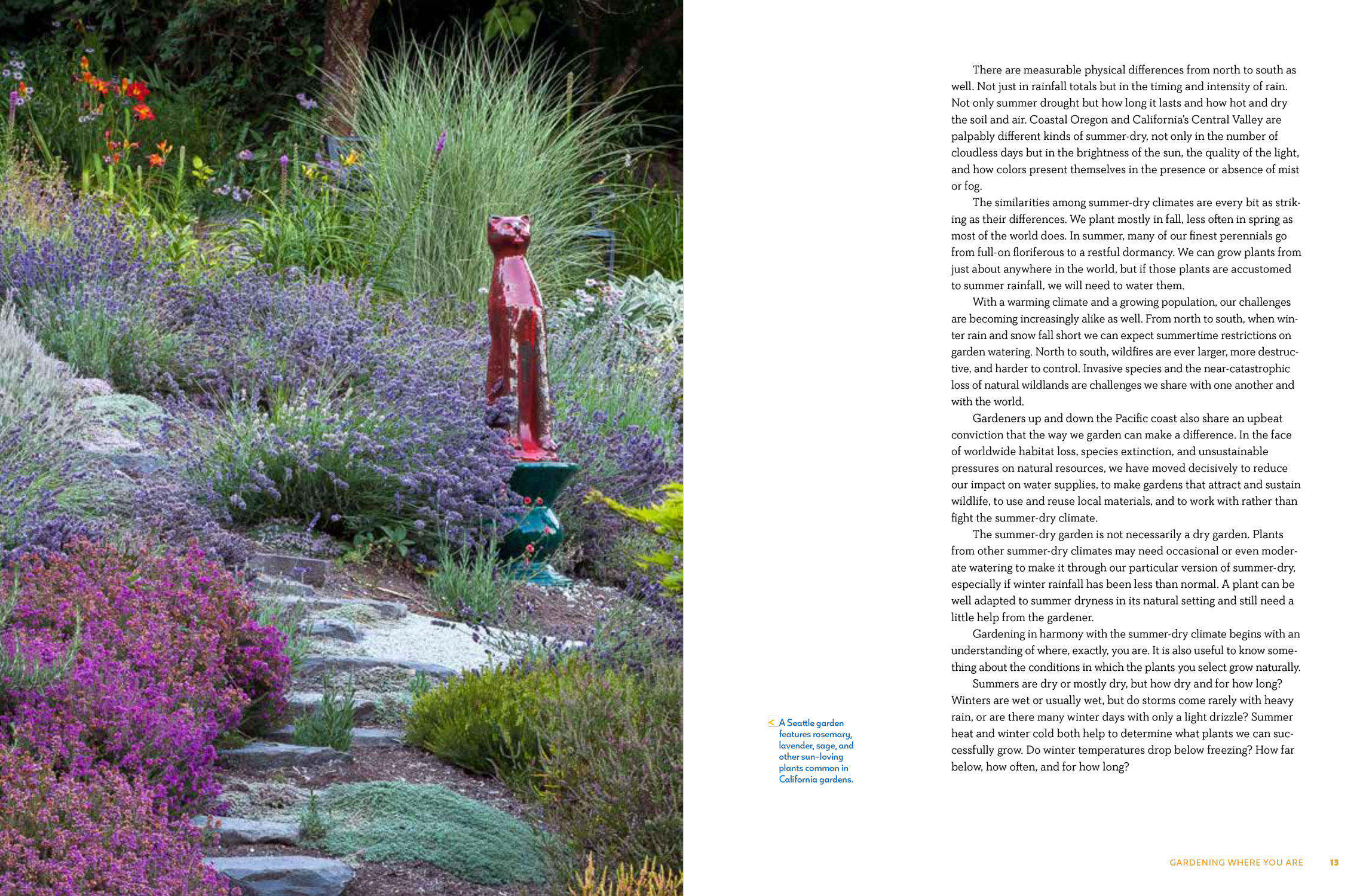

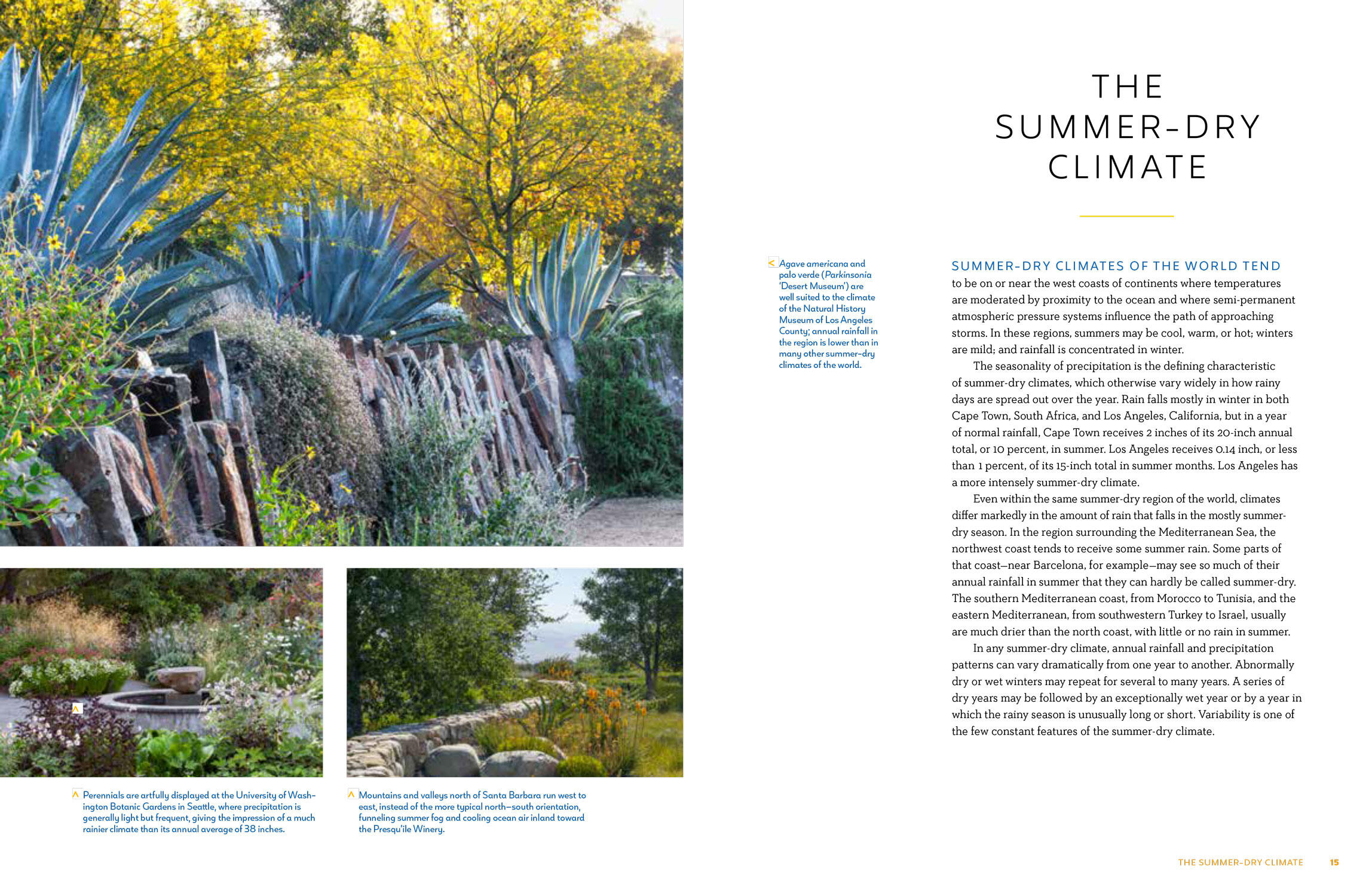

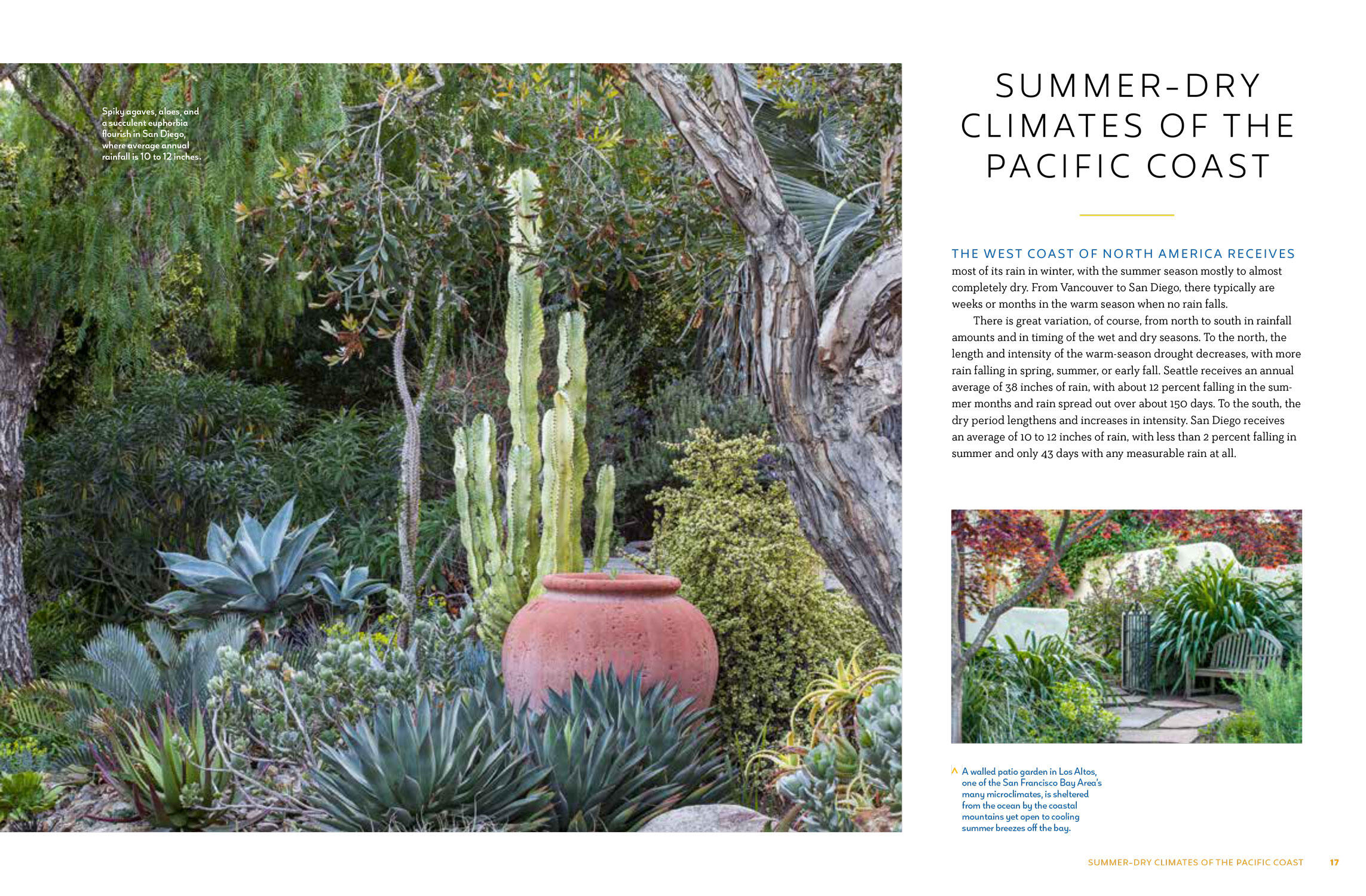

Selecting plants suited to your climate is the first step toward a thriving, largely self-sustaining garden that connects with and supports the natural world. With gentle and compelling text and stunning photographs of plants in garden settings, Gardening in Summer-Dry Climates by Nora Harlow and Saxon Holt is a guide to native and climate-adapted plants for summer-dry, winter-wet climates of North America’s Pacific coast. Knowing what these climates share and how and why they differ, you can choose to make gardens that maintain and expand local and regional biodiversity, take little from the earth that is not returned, and welcome and accommodate the presence of wildlife. With global warming, it is now even more critical that we garden in tune with climate.

Genre:

-

“The authors’ gentle plea to welcome a little wildness into our gardens is a timely and powerful message for all gardeners and landscape designers. Make room on your shelf for this beautiful new book.”B>Carol Bornstein, director of the Nature Gardens, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles CountyThe Oregonian

“An outstanding and beautiful contribution to horticultural literature on summer-dry gardening along the West Coast and beyond.”B>Bart O’Brien, director, Regional Parks Botanic Garden

“With stunning images and insightful text, Harlow and Holt ask us to embrace and celebrate our dry season with grace.”B>David Fross, owner, Native Sons Wholesale Nursery

“The authors’ clearly written text and Holt’s detailed and stunning photographs combine to create an informative guide for gardeners who hope to cultivate a lush landscape that minimizes their footprint on Garden Earth.” —The Oregonian

“A highly valuable guide to plants and planting design that would be useful in many regions of the country.” —Landscape Architecture

“An authoritative guide to planting and maintaining mostly native gardens that use minimal water, expand biodiversity, and delight the eye. A welcome addition to the canon of mindful gardening.” —Sunset

“From shrubs and flowers to succulents, grasses, and herbs, this book packs in all the recommended hardy plants a gardener could want. This makes it a snap to not just choose the best plant, but incorporate it into the right landscape choices.” —Donovan’s Bookshelf

“A solid plant guide, beautifully highlighted by Holt’s stunning photographs… a must-have book for your collection.” —The Designer

“A beautiful book that’s much more than a directory of drought-tolerant plants. It’s one that can help build a beautiful, largely self-sustaining space that suits its spot on the planet in both looks and needs.” B>Horticulture

“This source of excellent information is for everyone who wants a drought-tolerant garden.” B>The Napa Valley Register

“Fascinating chapters on the circumstances that create these unpredictable climates.”

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use