Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

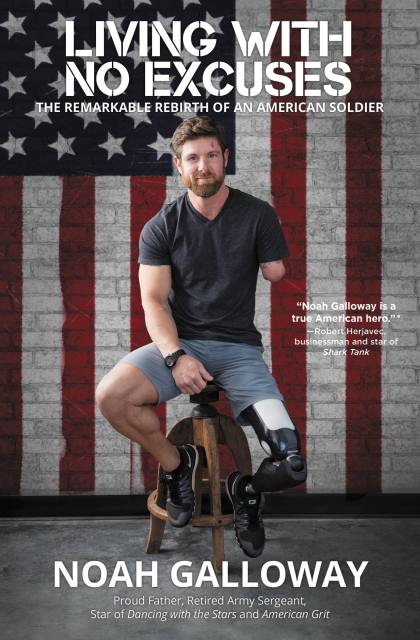

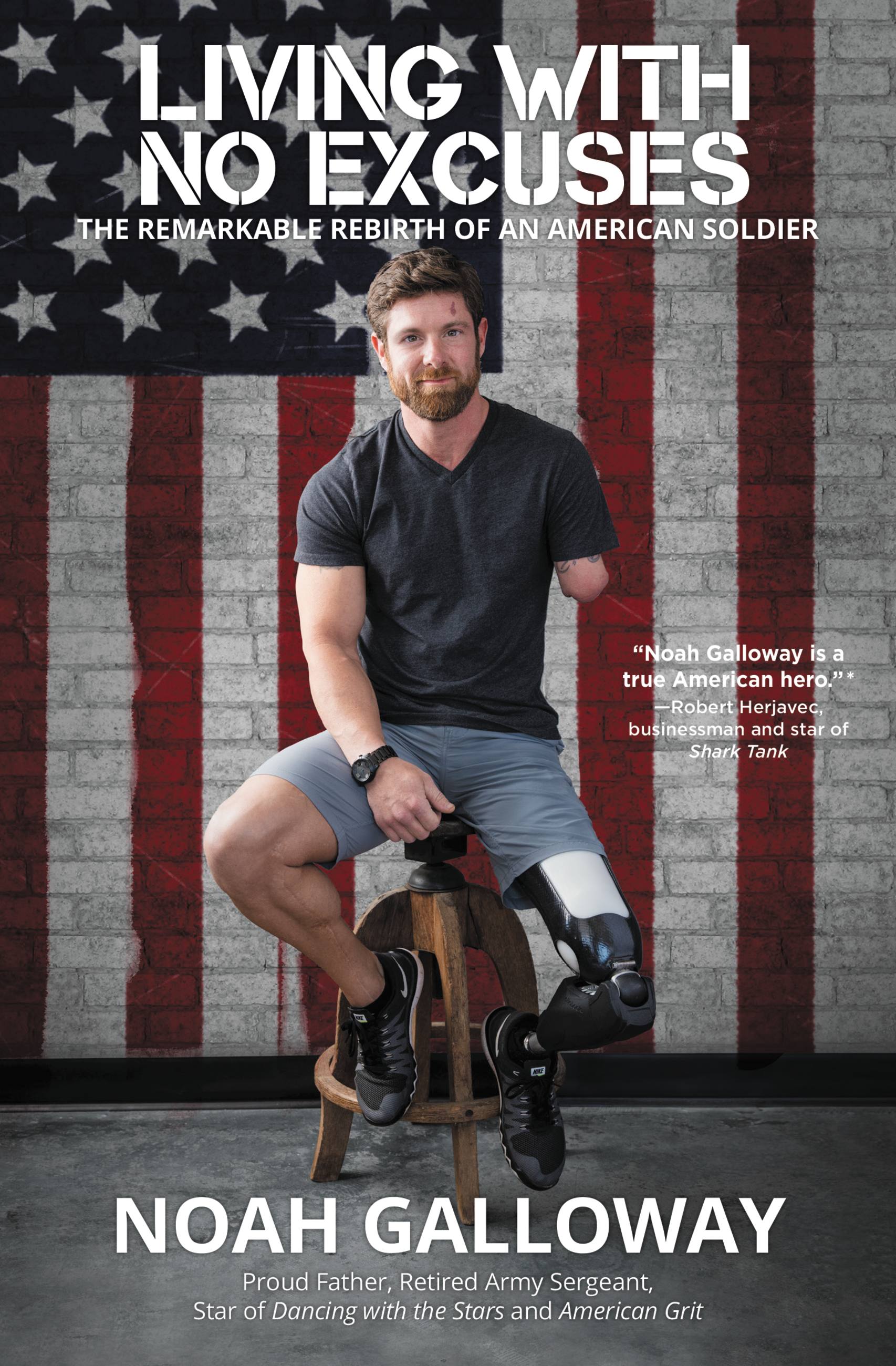

Living with No Excuses

The Remarkable Rebirth of an American Soldier

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 23, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Inspirational, humorous, and thought provoking, Noah Galloway’s LIVING WITH NO EXCUSES sheds light on his upbringing in rural Alabama, his military experience, and the battle he faced to overcome losing two limbs during Operation Iraqi Freedom. From reliving the early days of life to his acceptance of his “new normal” after losing his arm and leg in combat, Noah reveals his ambition to succeed against all odds.

Noah’s gripping story is a shining example that with laughter, and the right amount of perspective, you can tackle anything. Whether it be overcoming injury, conquering the Dancing with the Stars ballroom, or taking the next steps forward in life with his young family – Noah demonstrates how to live life to the fullest, with no excuses.

Noah’s gripping story is a shining example that with laughter, and the right amount of perspective, you can tackle anything. Whether it be overcoming injury, conquering the Dancing with the Stars ballroom, or taking the next steps forward in life with his young family – Noah demonstrates how to live life to the fullest, with no excuses.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Aug 23, 2016

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Center Street

- ISBN-13

- 9781455596928

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use