Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

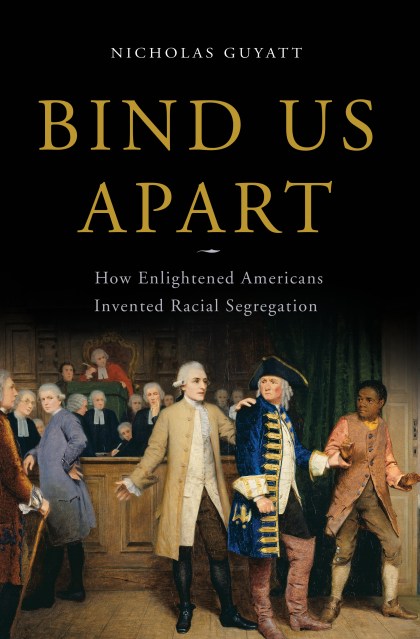

Bind Us Apart

How Enlightened Americans Invented Racial Segregation

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$20.99Price

$26.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $20.99 $26.99 CAD

- Hardcover $32.00 $40.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 26, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Herein lie the origins of “separate but equal.” Decades before Reconstruction, America’s liberal elite was unable to imagine how people of color could become citizens of the United States. Throughout the nineteenth century, Native Americans were pushed farther and farther westward, while four million slaves freed after the Civil War found themselves among a white population that had spent decades imagining that they would live somewhere else.

Essential reading for anyone disturbed by America’s ongoing failure to achieve true racial integration, Bind Us Apart shows conclusively that “separate but equal” represented far more than a southern backlash against emancipation-it was a founding principle of our nation.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Apr 26, 2016

- Page Count

- 416 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465065615

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use