Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

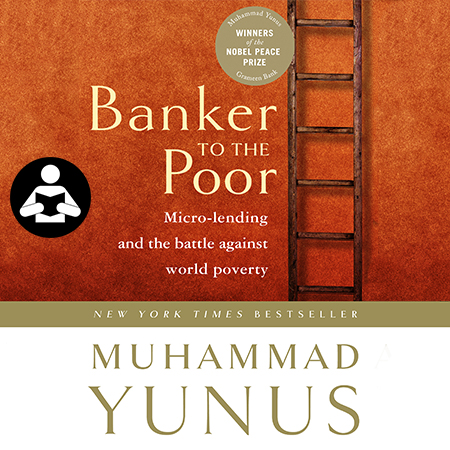

Banker To The Poor

Micro-Lending and the Battle Against World Poverty

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $15.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 16, 2003. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Muhammad Yunus was a professor of economics in Bangladesh, who realized that the most impoverished members of his community were systematically neglected by the banking system — no one would loan them any money. Yunus conceived of a new form of banking — microcredit — that would offer very small loans to the poorest people without collateral, and teach them how to manage and use their loans to create successful small businesses. He founded Grameen Bank based on the belief that credit is a basic human right, not the privilege of a fortunate few, and it now provides $24 billion of micro-loans to more than nine million families. Ninety-seven percent of its clients are women, and repayment rates are over 90 percent. Outside of Bangladesh, micro-lending programs inspired by Grameen have blossomed, and serve hundreds of millions of people around the world.

The definitive history of micro-credit direct from the man that conceived of it, Banker to the Poor is the moving story of someone who dreamed of changing the world — and did.

-

"By giving poor people the power to help themselves, Dr. Yunus has offered them something far more valuable than a plate of food - security in its most fundamental form."President Jimmy Carter

-

"[Yunus's] ideas have already had a great impact on the Third World, and ... hearing his appeal for a 'poverty-free world' from the source itself can be as stirring as that all-American myth of bootstrap success."Washington Post

-

"I only wish every nation shared Dr. Yunus's and the Grameen Bank's appreciation of the vital role that women play in the economic, social, and political life of our societies."Hillary Clinton

-

"Muhammad Yunus is a practical visionary who has improved the lives of millions of people in his native Bangladesh and elsewhere in the world. Banker to the Poor [is] well-reasoned yet passionate."Los Angeles Times

-

"A fascinating and compelling account by someone who decided to make a difference, and did."CHOICE

- On Sale

- Oct 16, 2003

- Page Count

- 312 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781586481988

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use