Promotion

Use code FALL24 for 20% off sitewide!

Julia Lathrop

Social Service and Progressive Government

Contributors

By Miriam Cohen

Formats and Prices

Price

$22.00Format

Format:

- Trade Paperback $22.00

- ebook $14.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 7, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Julia Lathrop was a social servant, government activist, and social scientist who expanded notions of women's proper roles in public life during the early 1900s. Appointed as chief of the U.S. Children's Bureau, created in 1912 to promote child welfare, she was the first woman to head a United States federal agency. Throughout her life, Lathrop challenged the social norms of the time and became instrumental in shaping Progressive reform. She began her career at Hull House in Chicago, the nation's most famous social settlement, where she worked to improve public and private welfare for poor people, helped establish America's first juvenile court, and pushed for immigrant rights. Lathrop was also co-founder of one of America's first schools of social work. Later in life she became a leader in the League of Women Voters and an advisor on child welfare to the League of Nations.

Following Lathrop's life from her childhood and college education through her social service and government work, this book gives an overview of her enduring contribution to progressive politics, women's employment, and women's education. It also offers a look at how one influential woman worked within the bounds of traditional conventions about gender, race, and class, and also pushed against them.

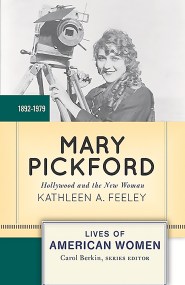

About the Lives of American Women series:

Selected and edited by renowned women's historian Carol Berkin, these brief biographies are designed for use in undergraduate courses. Rather than a comprehensive approach, each biography focuses instead on a particular aspect of a woman's life that is emblematic of her time, or which made her a pivotal figure in the era. The emphasis is on a “good read,” featuring accessible writing and compelling narratives, without sacrificing sound scholarship and academic integrity. Primary sources at the end of each biography reveal the subject's perspective in her own words. Study questions and an annotated bibliography support the student reader.

Series:

- On Sale

- Mar 7, 2017

- Page Count

- 192 pages

- Publisher

- Avalon Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780813348032

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use