By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

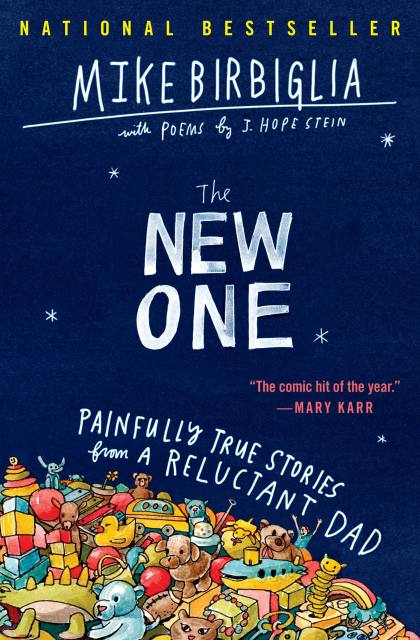

The New One

Painfully True Stories from a Reluctant Dad

Contributors

Supplement by J. Hope Stein

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 7, 2021

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538701522

Price

$16.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $14.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 7, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

With laugh-out-loud funny parenting observations, the New York Times bestselling author and award-winning comedian delivers a book that is perfect for anyone who has ever raised a child, been a child, or refuses to stop acting like one.

In 2016 comedian Mike Birbiglia and poet Jennifer Hope Stein took their fourteen-month-old daughter Oona to the Nantucket Film Festival. When the festival director picked them up at the airport she asked Mike if he would perform at the storytelling night. She said, “The theme of the stories is jealousy.”

Jen quipped, “You’re jealous of Oona. You should talk about that.”

And so Mike began sharing some of his darkest and funniest thoughts about the decision to have a child. Jen and Mike revealed to each other their sides of what had gone down during Jen’s pregnancy and that first year with their child. Over the next couple years, these stories evolved into a Broadway show, and the more Mike performed it the more he heard how it resonated—not just with parents but also people who resist all kinds of change.

So he pored over his journals, dug deeper, and created this book: The New One: Painfully True Stories From a Reluctant Dad. Along with hilarious and poignant stories he has never shared before, these pages are sprinkled with poetry Jen wrote as she navigated the same rocky shores of new parenthood.

So here it is. This book is an experiment—sort of like a family.

In 2016 comedian Mike Birbiglia and poet Jennifer Hope Stein took their fourteen-month-old daughter Oona to the Nantucket Film Festival. When the festival director picked them up at the airport she asked Mike if he would perform at the storytelling night. She said, “The theme of the stories is jealousy.”

Jen quipped, “You’re jealous of Oona. You should talk about that.”

And so Mike began sharing some of his darkest and funniest thoughts about the decision to have a child. Jen and Mike revealed to each other their sides of what had gone down during Jen’s pregnancy and that first year with their child. Over the next couple years, these stories evolved into a Broadway show, and the more Mike performed it the more he heard how it resonated—not just with parents but also people who resist all kinds of change.

So he pored over his journals, dug deeper, and created this book: The New One: Painfully True Stories From a Reluctant Dad. Along with hilarious and poignant stories he has never shared before, these pages are sprinkled with poetry Jen wrote as she navigated the same rocky shores of new parenthood.

So here it is. This book is an experiment—sort of like a family.

-

"Mike Birbiglia and Jen Stein are the best collaborators since Emily Dickinson teamed up with her long-winded comedian friend. I'm joking because I cannot express how much this book affected me and how many times it made me cry."John Mulaney, comedian

-

"Mike Birbiglia & J. Hope Stein have written the seminal parenting tome--side-splittingly funny from the first word to the last delicious bite. It's a page-turner, wise and wise-assed, the comic hit of the year. Whether you've been a parent or ever had one: you'll love this knockout!"Mary Karr, authorof The Liars' Club, Cherry, and Lit

-

"Life is not the same after having children. It's delusional to pretend otherwise. But Mike Birbiglia and J. Hope Stein have not only survived, they're making their most hilarious and truthful art yet. This book might save your best friend's life."Lin-Manuel Miranda, PulitzerPrize Winning writer of Hamilton

-

"Mike Birbiglia and Jen Stein are the best collaborators since Emily Dickinson teamed up with her long-winded comedian friend. I'm joking because I cannot express how much this book affected me and how many times it made me cry."John Mulaney, comedian

-

"This is a brilliant, funny, big-hearted version of he-said, she-said. Birbiglia and Stein trade jokes and poems and splendid storytelling about their roundabout stumble into parenthood. It's hilarious, humane, often beautiful, and absolutely captivating."Susan Orlean, staff writer at The New Yorker and New York Times bestselling author of The Library Book

-

"The genius of this book is that Mike Birbiglia and J. Hope Stein have invented a totally new form. He tells incredibly funny stories. She gives a gorgeous, epic view of the same events, in poetry (she's a published poet who's been in The New Yorker). It's about what they went through together, not wanting to have kids, and then having kids, through these two very different lenses. Their diabolical writing trick: sometimes she delivers the laughs and he delivers the feelings."Ira Glass, host of Public Radio's This American Life

-

"Fusing good humor and raw honesty with selections from Stein's evocative poetry, Birbiglia narrates his journey into parenting...Hilarious, relatable, cringeworthy, and effortlessly entertaining."Kirkus (starred review)

-

"In a 'town where everyone is pretending to be happy and pretending to be in good marriage and pretending to be in a nice house' it takes a poet and a comedian to tell us the truth. What is this truth? That we are lost, but trying to find ourselves, that we are awkward but long for grace, we are cruel but delight at the slightest drop of tenderness. This book is hilarious because it shows us a mirror that doesn't lie. It sings because words give delight in each simplest moment. Imagine Groucho Marx and Jane Kenyon sit at the kitchen table and compose a book of days. When nothing else helps, it is a sense of humor and a beautiful song that will get us through."Ilya Kaminsky, author of Deaf Republic and Dancing in Odessa

-

"I wish I had read The New One before having a kid. Mike confronts parenthood with the kind of devastating honesty that can't help but be funny, and Jen's poems capture what prose can't. In a better world, this book would be sold with every pregnancy test in America."Bess Kalb, author of Nobody WillTell You This But Me

-

"If The New One on Broadway is a raucous, tumbling tour through the many roomed house that is Mike and Jen's journey into parenthood, then this book is a long, cozy weekend inside the home. Mike makes you coffee and settles in to tell his story at a wonderfully readable pace, bringing detail and nuance impossible to contain in the stage show. Jen's poetry is the big stunner, an outrageous treasure casually presented, emeralds strewn amongst crumbs across the kitchen table, a string of pearls hanging on a doorknob."Jacqueline Novak, author of How to Weep in Public

-

"Expanded from his one-man show of the same name (and including poetry by his wife), comedian Birbiglia's rueful, hilarious take on new parenthood is a treat."People

-

"Comedian, actor, director, and producer Mike Birbiglia explores his mixed feelings about becoming a parent. His confessional and observational prose passages are interspersed with lyrical interludes written by his wife, poet J. Hope Stein...A lighthearted and uncomfortable portrait of fatherhood."Publishers Weekly

-

"Sex, sympathy weight, and Birbiglia's sleep disorder are all fair game in this hilariously, sometimes shockingly, and always refreshingly honest look at having a kid and becoming new one's self."Booklist

-

"Seasoned and rookie dads alike will appreciate Birbiglia's comic riffs on family life. His memoir is a can't-miss gift that's sure to make 'em laugh."Bookpage

-

"Reading this raw and vulnerable book was almost like opening a page into Mike Birbiglia's diary; his emotion is truly refreshing. He is a wonderful comedian who will have you laughing and crying and thinking, all in the span of a single chapter."Bookreporter

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use