Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

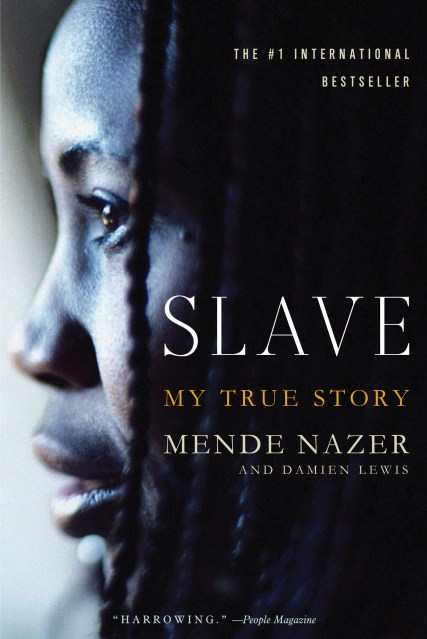

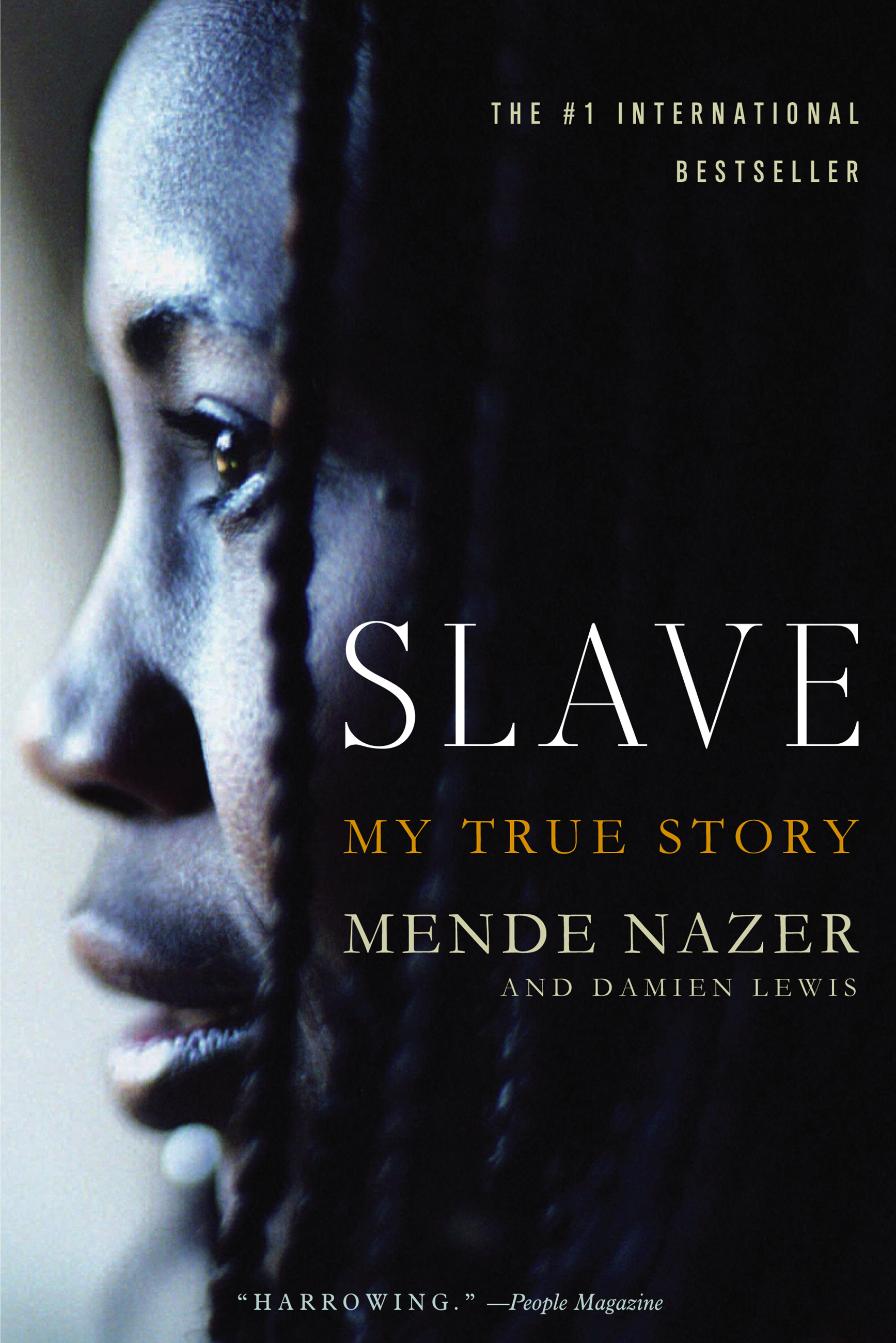

Slave

My True Story

Contributors

By Mende Nazer

By Damien Lewis

Formats and Prices

Price

$21.99Format

Format:

- Trade Paperback $21.99

- ebook $9.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 27, 2005. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Mende Nazer lost her childhood at age twelve, when she was sold into slavery. It all began one horrific night in 1993, when Arab raiders swept through her Nuba village, murdering the adults and rounding up thirty-one children, including Mende.

Mende was sold to a wealthy Arab family who lived in Sudan’s capital city, Khartoum. So began her dark years of enslavement. Her Arab owners called her “Yebit,” or “black slave.” She called them “master.” She was subjected to appalling physical, sexual, and mental abuse. She slept in a shed and ate the family leftovers like a dog. She had no rights, no freedom, and no life of her own.

Normally, Mende’s story never would have come to light. But seven years after she was seized and sold into slavery, she was sent to work for another master-a diplomat working in the United Kingdom. In London, she managed to make contact with other Sudanese, who took pity on her. In September 2000, she made a dramatic break for freedom.

Slave is a story almost beyond belief. It depicts the strength and dignity of the Nuba tribe. It recounts the savage way in which the Nuba and their ancient culture are being destroyed by a secret modern-day trade in slaves. Most of all, it is a remarkable testimony to one young woman’s unbreakable spirit and tremendous courage.

Mende was sold to a wealthy Arab family who lived in Sudan’s capital city, Khartoum. So began her dark years of enslavement. Her Arab owners called her “Yebit,” or “black slave.” She called them “master.” She was subjected to appalling physical, sexual, and mental abuse. She slept in a shed and ate the family leftovers like a dog. She had no rights, no freedom, and no life of her own.

Normally, Mende’s story never would have come to light. But seven years after she was seized and sold into slavery, she was sent to work for another master-a diplomat working in the United Kingdom. In London, she managed to make contact with other Sudanese, who took pity on her. In September 2000, she made a dramatic break for freedom.

Slave is a story almost beyond belief. It depicts the strength and dignity of the Nuba tribe. It recounts the savage way in which the Nuba and their ancient culture are being destroyed by a secret modern-day trade in slaves. Most of all, it is a remarkable testimony to one young woman’s unbreakable spirit and tremendous courage.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Apr 27, 2005

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781586483180

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use