By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

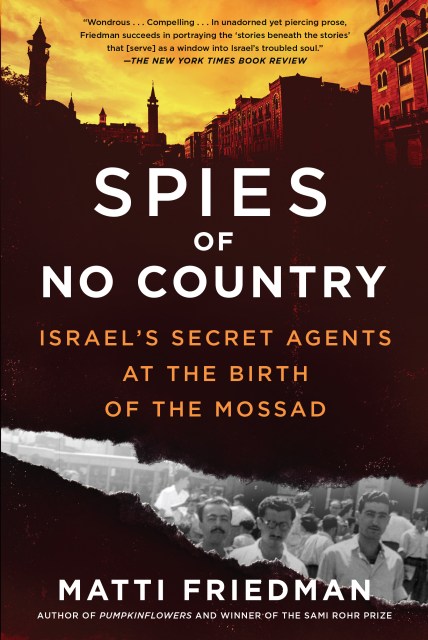

Spies of No Country

Israel's Secret Agents at the Birth of the Mossad

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$18.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 4, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

“Wondrous . . . Compelling . . . Piercing.” —The New York Times Book Review

Award-winning writer Matti Friedman’s tale of Israel’s first spies has all the tropes of an espionage novel, including duplicity, betrayal, disguise, clandestine meetings, the bluff, and the double bluff—but it’s all true.

The four spies were young, Jewish, and born in Arab countries. In 1948, at the outbreak of war in Palestine, they went undercover in Beirut, spending two years running sabotage operations and sending crucial intelligence back home. It was dangerous work. Of the dozen members of their ragtag unit, five would be caught and executed—but the remainder would emerge as the nucleus of the Mossad, Israel’s vaunted intelligence agency.

Journalist and award-winning author Matti Friedman’s masterfully told and meticulously researched tale of Israel’s first spies reads like an espionage novel—but it’s all true. Spies of No Country is about the slippery identities of these spies, but it’s also about the complicated identity of Israel, a country that presents itself as Western but in fact has more citizens with Middle Eastern roots, just like the spies of this fascinating narrative.

Award-winning writer Matti Friedman’s tale of Israel’s first spies has all the tropes of an espionage novel, including duplicity, betrayal, disguise, clandestine meetings, the bluff, and the double bluff—but it’s all true.

The four spies were young, Jewish, and born in Arab countries. In 1948, at the outbreak of war in Palestine, they went undercover in Beirut, spending two years running sabotage operations and sending crucial intelligence back home. It was dangerous work. Of the dozen members of their ragtag unit, five would be caught and executed—but the remainder would emerge as the nucleus of the Mossad, Israel’s vaunted intelligence agency.

Journalist and award-winning author Matti Friedman’s masterfully told and meticulously researched tale of Israel’s first spies reads like an espionage novel—but it’s all true. Spies of No Country is about the slippery identities of these spies, but it’s also about the complicated identity of Israel, a country that presents itself as Western but in fact has more citizens with Middle Eastern roots, just like the spies of this fascinating narrative.

-

2019 National Jewish Book Awards finalistYossi Klein Halevi, New York Times bestselling author of Letters to My Palestinian Neighbor

“Wondrous . . . compelling . . . In unadorned yet piercing prose, Friedman captures what it was like to be part of the Arab Section . . . Friedman succeeds in portraying the ‘stories beneath the stories’ that acted as a bedrock to the rise of the Mossad and serve still as a window into Israel’s troubled soul.”

B>New York Times Book Review

“Spies of No Country is an important book . . . Americans are not accustomed to hearing about Israel's complexity, or its diversity. We are rarely asked to consider Israel as a country that is, as Friedman says, 'more than one thing.' Any serious defender or critic of Israeli politics should consider this a serious problem. Meaningful opinions require nuanced understanding, and Spies of No Country offers that.”

B>NPR Books

“In Spies of No Country, Matti Friedman, a Canadian-Israeli journalist, resurrects early operations of the intelligence service of the Palmach, the nascent military that ultimately grew into the mighty Israel Defense Forces. The book is a slim but intriguing string of anecdotes in which members of the unit risk their lives under cover in Syria, Lebanon and Iraq as Jewish settlers and refugees fought to preserve their foothold in Palestine.”

B>The Wall Street Journal

“Engaging . . . Illuminating . . . Friedman seems to be telling this story for larger purposes. He wants to shine a light on a band of Arab-born operatives often overlooked in the stories of Israel’s founding as a Holocaust refuge led by Europeans in the Zionist movement. When I was done, I couldn’t stop thinking about the men inside the Beirut kiosk, selling candy and pencils to schoolchildren while secretly listening to a transistor radio tucked in the back, trying to pick up news from home.”

B>The Washington Post

“One of the most compelling, compulsively readable histories I've read in a long while. Matti Friedman is a lyrical writer and a master of suspenseful storytelling. His gripping spy story doesn’t just narrate Israel’s heroic founding—it illuminates its tortured present.”

B>Franklin Foer, author of World Without Mind

“Spies of No Country is thrilling, moving, and, like everything that Matti Friedman writes, deeply humane.”

B>Nicole Krauss, author of Forest Dark

"A thrilling Israeli spy story . . . Matti Friedman tells this story with great style. Not only is Spies of No Country good on such sophisticated, tangled questions of identity; it also just tells a fun story. As a literary document, Spies of No Country is exquisite . . . beautiful and exciting.”

I>The Forward

“Matti Friedman’s Spies of No Country is a compelling tale of Israeli espionage. But more than that, it is a meditation on Israel’s national origin story . . . compelling . . . like the best le Carré . . . Friedman’s superb storytelling skills are such that he employs the devices of fiction, most notably the use of dramatic irony, which gives the narrative a particular poignancy.”

I>The American Interest

“Matti Friedman’s enthralling new book, Spies of No Country, tells the story of a Palmach unit called the Arab Section. The Palmach was the underground Jewish army that fought in British Palestine.”

B>Commentary Magazine

“On the surface, it’s an engaging spy saga. Beneath that, though, lies an examination of identity and the humanity behind both sides of the ongoing Arab-Israeli conflict. Ultimately, Gamliel, Isaac, Havakuk, and Yakuba were unknown until now because they were not caught and thus escaped greater renown. Matti Friedman does us, his readers, a great service not just in bringing their exploits to light, but in sharing with us insights into how they impacted history and the region.”

I>Washington Independent Review of Books

“Excellent . . . compelling . . . [the spies’] stories are an unjustly forgotten—and fascinating—aspect of Israel’s founding. [Friedman’s] deeply researched book is not only enjoyable but groundbreaking.”

I>Jewish Review of Books

“A noteworthy and authentic spy story. Spies of No Country tells the story of the birth of the State of Israel in 1948 through the accounts of a small group of Jewish heroes, the Arab Section, who spied for the new state in surrounding Arab countries . . . filled with riveting vignettes. This is rather a splendid retelling of one small part of the effort to create a Jewish homeland. Friedman’s account of the Arab Section is an eye-opening narrative of the early days of the State of Israel. It is not an optimistic story, but a genuine and sorrowful one.”

B>The New York Journal of Books

“Spies of No Country, the third book by the Israeli journalist, shares the gripping and previously untold stories of four Mizrahi Jews who took part in a spy unit called the Arab Section. Friedman’s approach to this often untold history of Israel is a refreshing one – and has been taboo for many writers. The rich history of Eastern Jews, including the critical role they played in establishing the State of Israel, should not be minimized or erased by the superficial biases of Western scholars. Thankfully, Friedman’s groundbreaking book provides a vital example of how to avoid just that.”

I>Jerusalem Post

“We learn more about what a real-life espionage agent actually does in Spies of No Country than in any mere thriller . . . so exotic that it sounds like something out of the imagination of Ian Fleming. Friedman’s book is animated by his conviction that respect must be paid to these overlooked heroes. Thus does Friedman rectify a moral and historical wrong when he calls our attention to the four young men whom we come to know so well and admire so much in the pages of Spies of No Country.”

I>Jewish Journal (Los Angeles)

“Matti Friedman’s Spies of No Country tells the story of four men who became members of the Arab Section and went undercover in Beirut for two years. Readers who know Friedman from his previous books, Pumpkinflowers and The Aleppo Codex, will already appreciate Friedman’s talent in creating dramatic nonfiction. A spy story inherently involves situations that complicate the life of the main character. Friedman enhances his story by defining how his character perceives the situations he encounters, but also how he, the writer, perceives the character perceiving the situation.”

I>Jewish Herald-Voice (Houston)

“Refreshing . . . Friedman’s book exposes the complex reality of these loyal Israelis who were challenged, exoticized and vilified again and again by Ashkenazi Jews. The rich history of Eastern Jews, including the critical role they played in establishing the State of Israel, should not be minimized or erased by the superficial biases of Western scholars. Thankfully, Friedman’s groundbreaking book provides a vital example of how to avoid just that.”

I>Jewish Star

“Sometimes we read books that fill in details about a particular moment in the history we care deeply about, and we learn so much. Matti Friedman has written such a book about the Jewish spies who spoke Arabic as their native language because they had grown up in places like Syria, Yemen and Jerusalem during the British mandate before Israel became an embattled state in May 1948. Friedman’s reporting on this moment in the formative time in Israeli history is helpful today as we watch events unfold that give hope for better relations between Israeli Jews and their Arab neighbors.”

B>St. Louis Jewish Light

“Veiling their Jewishness, the spies of the ‘Arab Section’ were present at the creation of Israel. Matti Friedman tells their little-known story. Friedman is a skilled storyteller with an eye for detail, and grounded in facts.”

B>The New York Jewish Week

“Remarkable . . . a fascinating account . . . a wealth of information and various tidbits that make it so worthwhile to read. With so much anti-Israel bias currently going on, this book serves as a truthful and unbiased account of the founding of the State of Israel. I would definitely recommend Spies of No Country to anybody who wants to learn more about Israel and Zionism in general.”

B>Manhattan Book Review

“In his new book, Spies of No Country, Friedman, who is now based in Jerusalem, combines his in-depth knowledge of Israel with a riveting narrative to recount the story of the Arab Section, an Israeli spy operation active from January 1948 to August 1949. Based on both interviews and archives, Friedman drops readers into the complex, shifting and dangerous landscape of the 1948 conflict. Spies of No Country is a fascinating journey into the past that reads like a spy novel—except in this case, it’s all true.”

B>BookPage

“Friedman tells the fascinating story of the Arab Section . . . At that time, Israel was many things, and the author deftly navigates the complicated identities and the stories beneath the stories. An exciting historical journey and highly informative look at the Middle East with Israel as the starting point.”

B>Kirkus Reviews

“In evocative prose detailing mid-20th-century life in the dangerous streets of Haifa and Beirut, journalist Friedman recounts the intertwined stories of four underground spies for the Arab Section of the Haganah, a Jewish paramilitary organization in Palestine that became part of the Israel Defence Forces after Israel’s founding.”

B>Publishers Weekly

“[An] absolutely arresting account of espionage at the genesis of the Israeli state.”

B>Booklist (starred review)

“At that time, Israel was many things, and the author deftly navigates the complicated identities and the stories beneath the stories . . . An exciting historical journey and highly informative look at the Middle East with Israel as the starting point.”

I>Kirkus Reviews

"A fine, moving piece of writing, told with simplicity and artistry."

B>Benny Morris, author of 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War

“This book sure looks like a rollicking spy story. It’s got all the necessary parts: a high-stakes war for a new state’s existence, double identities, suspense, betrayal. But it’s more than that. This is a book about being an outsider many times over. The four spies in Spies of No Country grew up as Jews in Arab lands; came of age in British Palestine as dark-skinned Middle Easteners looked down on by their European counterparts; lived undercover as Arabs in hostile territory; and were never publicly acknowledged in Israel as the heroes they were. Justice demanded that their stories be told. We’re lucky that a writer as gifted as Matti Friedman came along to tell them.”

B>Judith Shulevitz, New York Times op-ed contributor and author of The Sabbath World

“Matti Friedman shows us how an heroic little band of Jewish spies from Arab countries helps explain the political and cultural transformation of Israel from its European Jewish origins into the largely Middle Eastern country it is today. With Spies of No Country, Matti Friedman proves that he is one of the essential interpreters of Israel writing today.”

- On Sale

- Feb 4, 2020

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Algonquin Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781643750439

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use