Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

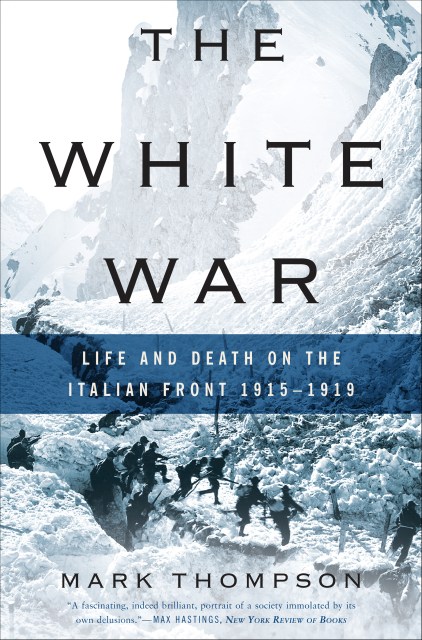

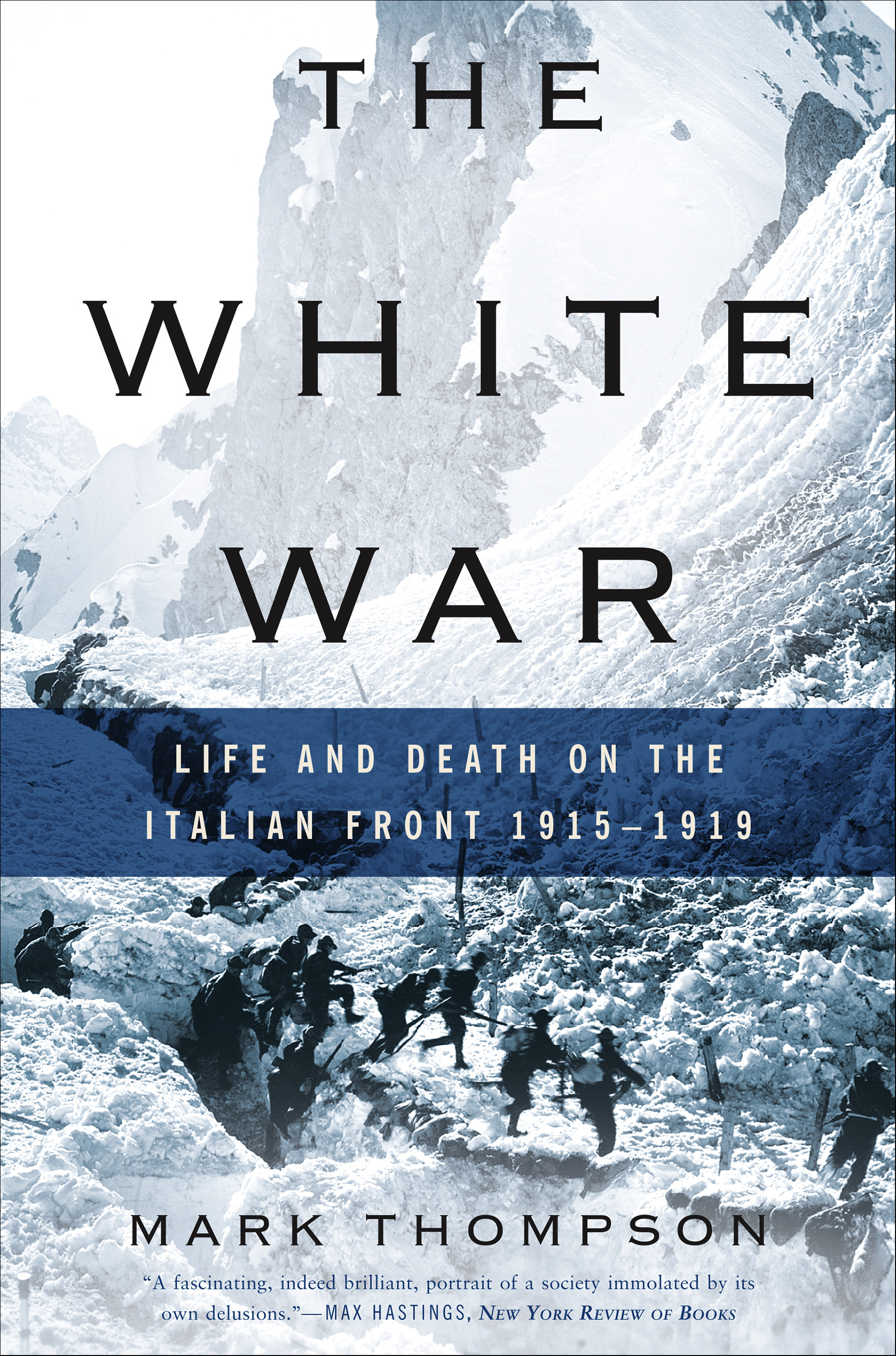

The White War

Life and Death on the Italian Front 1915-1919

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$21.99Price

$27.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $27.99 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 26, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

With elegance and pathos, historian Mark Thompson relates the saga of the Italian front, the nationalist frenzy and political intrigues that preceded the conflict, and the towering personalities of the statesmen, generals, and writers drawn into the heart of the chaos. A work of epic scale, The White War does full justice to the brutal and heart-wrenching war that inspired Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Oct 26, 2010

- Page Count

- 488 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465020379

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use