Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

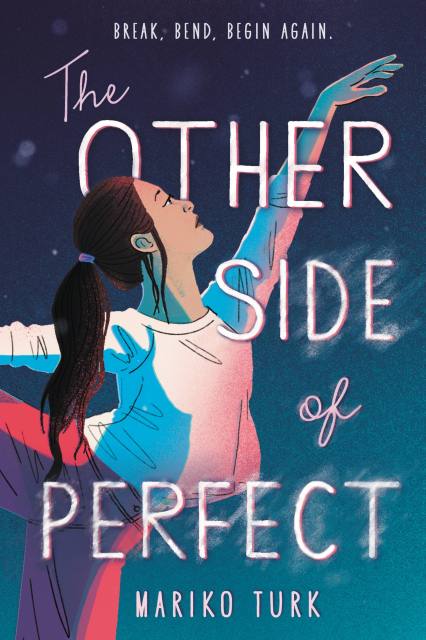

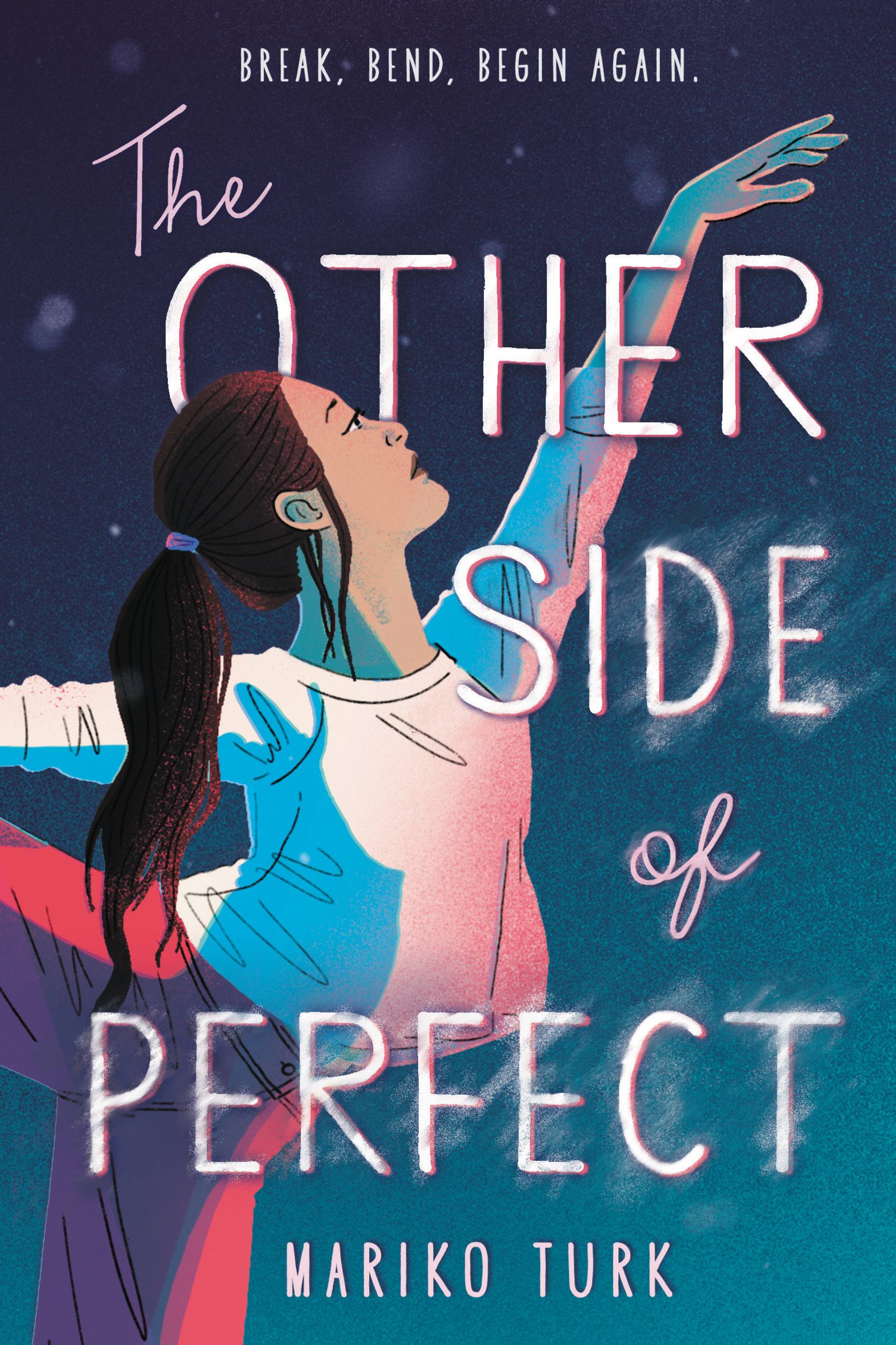

The Other Side of Perfect

Contributors

By Mariko Turk

Formats and Prices

Price

$10.99Price

$14.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $10.99 $14.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Hardcover $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 19, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

For fans of Sarah Dessen and Mary H.K. Choi, this lyrical and emotionally driven novel follows Alina, a young aspiring dancer who suffers a devastating injury and must face a world without ballet—as well as the darker side of her former dream.

Alina Keeler was destined to dance, but then a terrifying fall shatters her leg—and her dreams of a professional ballet career along with it.

After a summer healing (translation: eating vast amounts of Cool Ranch Doritos and binging ballet videos on YouTube), she is forced to trade her pre-professional dance classes for normal high school, where she reluctantly joins the school musical. However, rehearsals offer more than she expected—namely Jude, her annoyingly attractive castmate she just might be falling for.

But to move forward, Alina must make peace with her past and face the racism she experienced in the dance industry. She wonders what it means to yearn for ballet—something so beautiful, yet so broken. And as broken as she feels, can she ever open her heart to someone else?

Touching, romantic, and peppered with humor, this debut novel explores the tenuousness of perfectionism, the possibilities of change, and the importance of raising your voice.

-

Praise for The Other Side of Perfect:Booklist

- YALSA's 2022 Best Fiction For Young Adults

"Debut novelist Turk writes with a great deal of nuance.... A well-choreographed story of hope, resilience, and personal growth." -

"The writing is engaging, sentimental moments will please romance lovers, and the hopeful, yet realistic, ending is satisfying. A love story with a refreshing focus on confronting systemic racism."Kirkus

-

"A strong portrayal of musical theater, ballet, the arts, and culture all merged into a coming-of-age story that will resonate."SLJ

- On Sale

- Jul 19, 2022

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Poppy

- ISBN-13

- 9780316703413

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

Praise

-

Praise for The Other Side of Perfect:Booklist

– YALSA's 2022 Best Fiction For Young Adults

"Debut novelist Turk writes with a great deal of nuance…. A well-choreographed story of hope, resilience, and personal growth." -

"The writing is engaging, sentimental moments will please romance lovers, and the hopeful, yet realistic, ending is satisfying. A love story with a refreshing focus on confronting systemic racism."Kirkus

-

"A strong portrayal of musical theater, ballet, the arts, and culture all merged into a coming-of-age story that will resonate."SLJ