Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

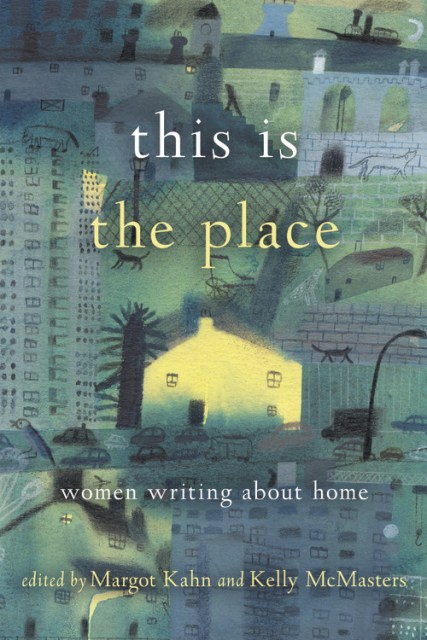

This Is the Place

Women Writing About Home

Contributors

Edited by Margot Kahn

Edited by Kelly McMasters

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$23.50 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $23.50 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 14, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

What makes a home? What do equality, safety, and politics have to do with it? And why is it so important to us to feel like we belong? In this collection, 30 women writers explore the theme in personal essays about neighbors, marriage, kids, sentimental objects, homelessness, domestic violence, solitude, immigration, gentrification, geography, and more. Contributors — including Amanda Petrusich, Naomi Jackson, Jane Wong, and Jennifer Finney Boylan — lend a diverse range of voices to this subject that remains at the core of our national conversations. Engaging, insightful, and full of hope, This is the Place will make you laugh, cry, and think hard about home, wherever you may find it.

“This collection, encompassing a spectrum of races, ethnicities, religions, sexualities, political beliefs and classes, could not be timelier . . . open this book, hear its chorus of voices and remember that we are a nation of individuals, bound to each other by our humanity.” — The New York Times Book Review

” . . . an honest portrait of the U.S., pieced together like an imperfect American quilt. We need more books like this.” — BUST

Genre:

- On Sale

- Nov 14, 2017

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580056687

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use