Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

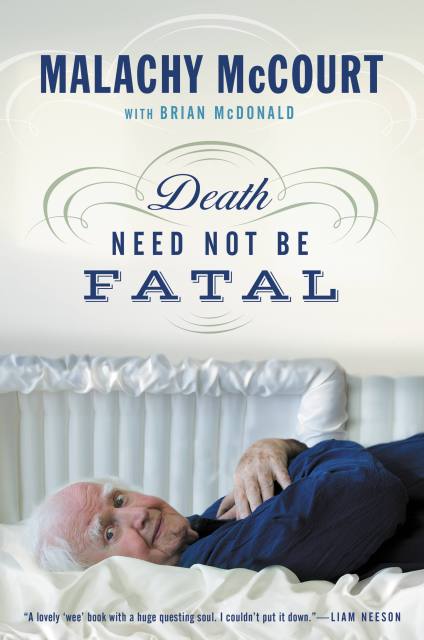

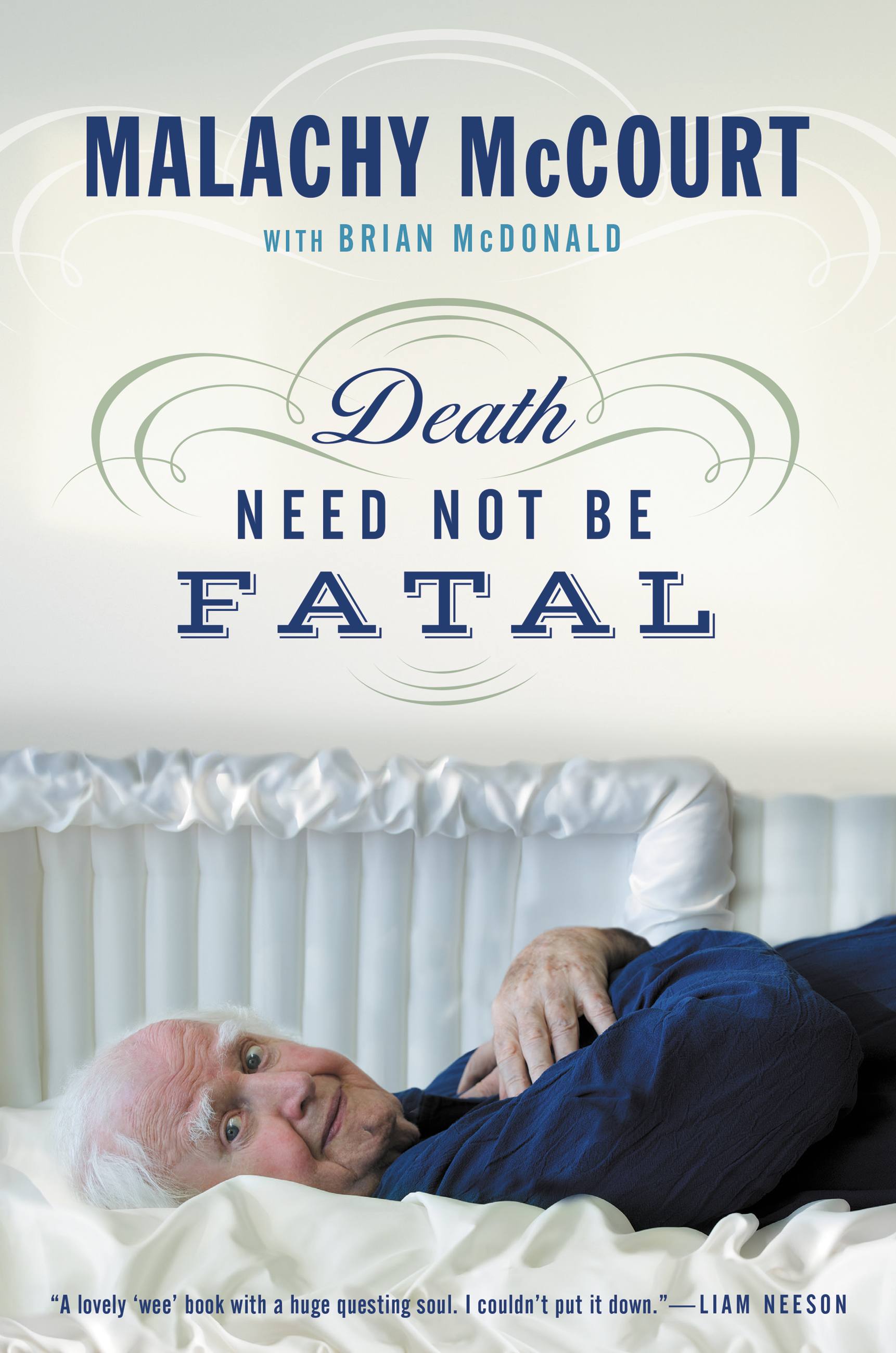

Death Need Not Be Fatal

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Hardcover $36.00 $46.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $15.99 $20.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 16, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

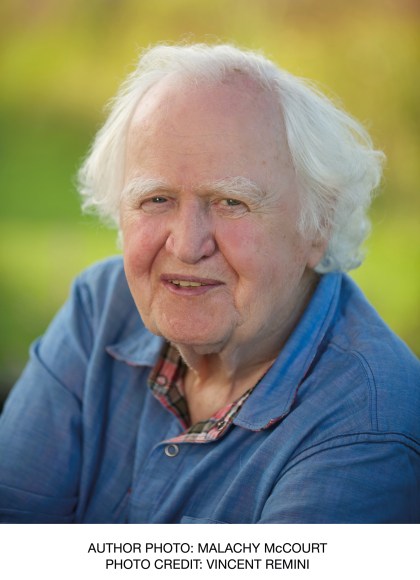

During the course of his life, Malachy McCourt practically invented the single’s bar; was a pioneer in talk radio, a soap opera star, a best-selling author; a gold smuggler, a political activist, and a candidate for governor of the state of New York.

It seems that the only two things he hasn’t done are stick his head into a lion’s mouth and die. Since he is allergic to cats, he decided to write about the great hereafter and answer the question on most minds: What’s so great about it anyhow?

In Death Need Not Be Fatal, McCourt also trains a sober eye on the tragedies that have shaped his life: the deaths of his sister and twin brothers; the real story behind Angela’s famous ashes; and a poignant account of the death of the man who left his mother, brothers, and him to nearly die in squalor. McCourt writes with deep emotion of the staggering losses of all three of his brothers, Frank, Mike, and Alphie. In his inimitable way, McCourt takes the grim reaper by the lapels and shakes the truth out of him.

As he rides the final blocks on his Rascal scooter, he looks too at the prospect of his own demise with emotional clarity and insight. In this beautifully rendered memoir, McCourt shows us how to live life to its fullest, how to grow old without acting old, and how to die without regret.

Genre:

-

"The idea of death may indeed take away a lot of things, but it cannot take away a great man's sense of humour. Malachy McCourt, as always, goes to the coalface and manages to dig out a tunnel of light."Colum McCann, author of Let the Great World Spin

-

"A lovely 'wee' book with a huge questing soul. Written with a twinkle in one eye and a tear in the other. Mr. McCourt writes with an openness and rawness about a Dickensian childhood and a life richly lived thereafter, discovering along the way the liberation of true forgiveness and the healing quality of love. I couldn't put it down."Liam Neeson

-

"Malachy McCourt's new book DEATH NEED NOT BE FATAL is one you must get and read and weep and laugh and sing over! A fabulous, funny, joyous journey. McCourt's own life and stories are hilarious and heartbreaking. Celebrate the laughter and the Irish humor that makes us all remember what it takes to do our time here, determined to live forever. DEATH NEED NOT BE FATAL will help you remember who you are and who you love. I loved it!"Judy Collins

-

"Malachy McCourt is a born storyteller. The colorful reflections on his life and his musings about death are lyrical and bittersweet, and of course given the author, filled with humor."Ed Burns

-

"McCourt returns to the twin balms the Irish have relied on forever: laughter and song. A wake in book form, his new memoir, written with Brian McDonald, is chock full of lyrics and verses from McCourt's favorite songs and poems as well as tales that may or may not be true, but are quite funny even when - maybe, especially when - they deal with death."The Washington Post

-

"Much of his humor is near to tears."p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; text-align: center; font: 16.0px Helvetica}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}Michael D. Langan, The Buffalo News

-

"Malachy McCourt's DEATH NEED NOT BE FATAL packs potent reflections on life."New York Daily News

-

"A lyrical memoir."AARP

-

"This is one of those books where you ration pages because you want it to last. [...] In a world at risk of drowning in memoirs, often by those who have not lived enough to pen so much as a substantial chapter, I beg you to read this by a man who lived ever so well and wrote about it lyrically."Jacqueline Cutler, NJ Advance Media

-

"At 85, Malachy McCourt swears to one and all he's in the Departure Lounge of his life now, but there are few of his age filled with as much fire. Although he insists in his own words he will soon "expire, depart, ascend and vanish," the truth is he has more to say now - hilariously and heart-rendingly - than ever."IrishCentral.com

-

"An unrepentant storyteller, he is back with a book on what is clearly on his mind these days, DEATH NEED NOT BE FATAL."Publishers Weekly

-

"DEATH NEED NOT BE FATAL captures 80+ years of living, from growing up in poverty in Limerick, Ireland to escaping back to New York where he was born. McCourt has seen - and done - it all, except die of course. He owned a popular bar in the city, became a television actor and wrote some best-selling books. He even ran against Elliot Spitzer in 2006 for governor of New York. [...] with eight decades and counting under his belt, he's seen his share of tragedies, too. But despite it all he's able to reflect on what it means to live life."Turney Duff, CNBC

- On Sale

- May 16, 2017

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Center Street

- ISBN-13

- 9781478917052

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use