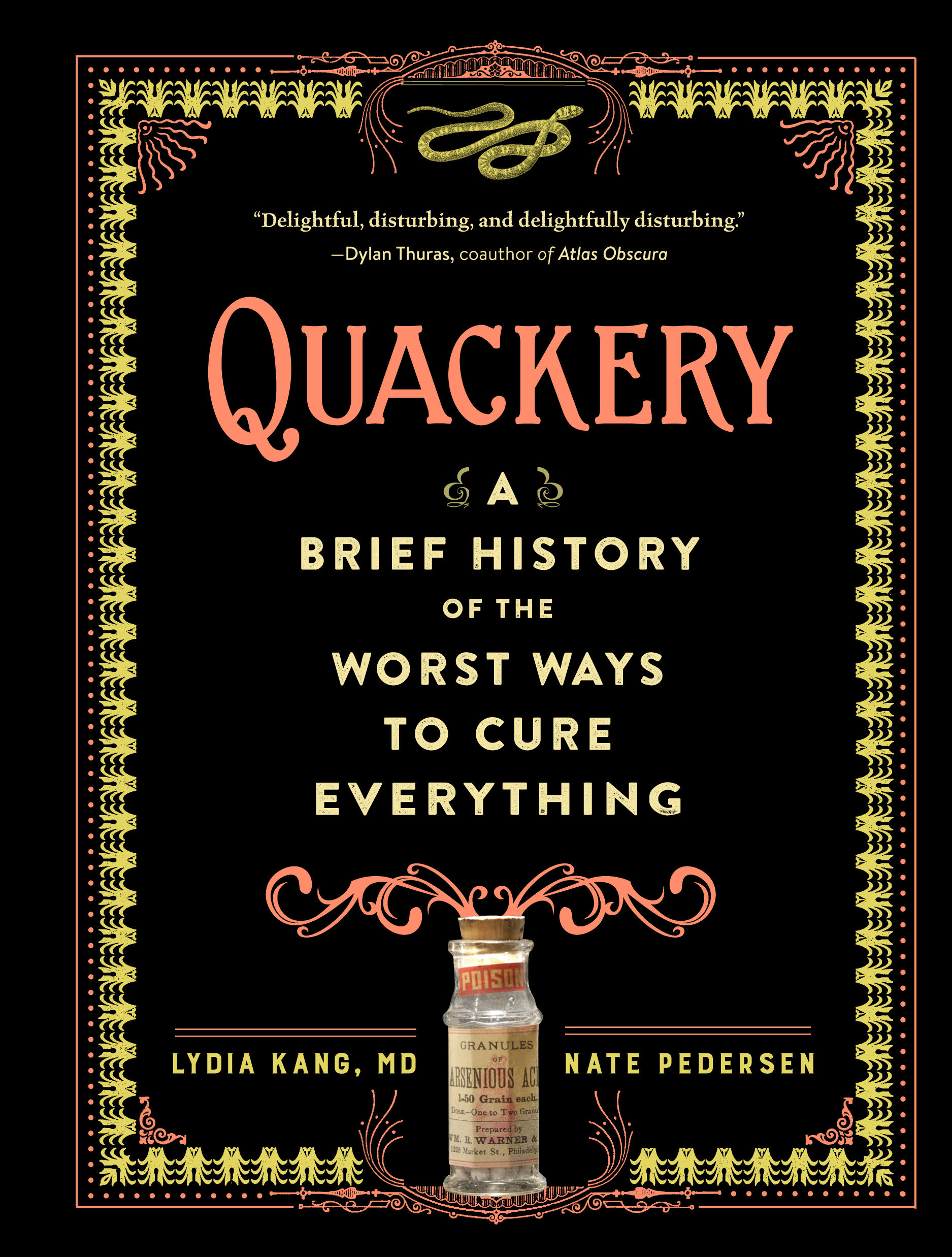

Quackery

A Brief History of the Worst Ways to Cure Everything

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$27.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $27.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 17, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

What won’t we try in our quest for perfect health, beauty, and the fountain of youth?

Well, just imagine a time when doctors prescribed morphine for crying infants. When liquefied gold was touted as immortality in a glass. And when strychnine—yes, that strychnine, the one used in rat poison—was dosed like Viagra.

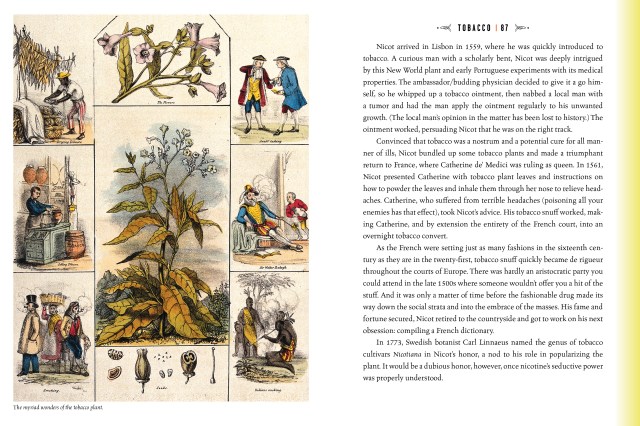

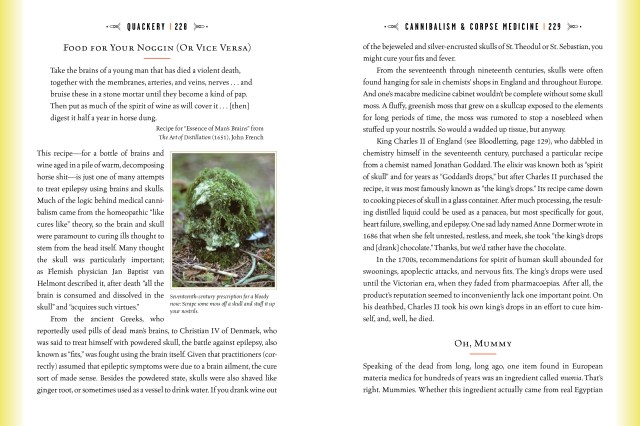

Looking back with fascination, horror, and not a little dash of dark, knowing humor, Quackery recounts the lively, at times unbelievable, history of medical misfires and malpractices. Ranging from the merely weird to the outright dangerous, here are dozens of outlandish, morbidly hilarious “treatments”—conceived by doctors and scientists, by spiritualists and snake oil salesmen (yes, they literally tried to sell snake oil)—that were predicated on a range of cluelessness, trial and error, and straight-up scams. With vintage illustrations, photographs, and advertisements throughout, Quackery seamlessly combines macabre humor with science and storytelling to reveal an important and disturbing side of the ever-evolving field of medicine.

Well, just imagine a time when doctors prescribed morphine for crying infants. When liquefied gold was touted as immortality in a glass. And when strychnine—yes, that strychnine, the one used in rat poison—was dosed like Viagra.

Looking back with fascination, horror, and not a little dash of dark, knowing humor, Quackery recounts the lively, at times unbelievable, history of medical misfires and malpractices. Ranging from the merely weird to the outright dangerous, here are dozens of outlandish, morbidly hilarious “treatments”—conceived by doctors and scientists, by spiritualists and snake oil salesmen (yes, they literally tried to sell snake oil)—that were predicated on a range of cluelessness, trial and error, and straight-up scams. With vintage illustrations, photographs, and advertisements throughout, Quackery seamlessly combines macabre humor with science and storytelling to reveal an important and disturbing side of the ever-evolving field of medicine.

Genre:

-

“[A]n insightful look at human hubris in the story of would-be cures of all our ailments.” —NPR’s Science Friday

“Much more than simply an overview of radioactive suppositories and mummy powder, Quackery is a thrilling dive into the human desire to live, to thrive, and the incredible power of belief. Delightful, disturbing, and delightfully disturbing, Quackery shares fascinating medical tales from throughout the ages, including the age we live in. It astonishes with the history of what patients once did in the name of ‘health’ and makes you wonder what we will one day look back on with equal shock.”

—Dylan Thuras, coauthor of Atlas Obscura

“Fascinating, fun, and occasionally infuriating. . . . a cautionary tale that should resonate even today—a reminder that when it comes to health care, being an informed consumer may indeed save your life.”

—Deborah Blum, author of The Poisoner’s Handbook: Murder and the Birth of Forensic Medicine in Jazz-Age New York

“Quackery brilliantly educates and entertains through the errors of doctors and scientists of the past. An entertaining read that will shock you and change how you view the health claims on products that we see daily.”

—David B. Agus, MD, author of the New York Times #1 bestseller The End of Illness and Professor of Medicine and Engineering, University of Southern California

“A bubbling elixir of the comically useless, the wildly hyped, and the just plain weird in would-be cures through history. Peel away those quaint old patent medicine labels and add some modern buzzwords, and marvel at how much has (and yet hasn’t really) changed.”

—Paul Collins, author of The Murder of the Century: The Gilded Age Crime That Scandalized a City and Sparked the Tabloid Wars

“Next time someone reminisces to you about the good old days, remind them how people used to wash their faces with arsenic, rub on radium liniment, and give each other tobacco smoke enemas. This compulsively readable compendium is a great reminder that medicine in the old days was often worse than the disease—and that there’s always reason to be wary of ‘miracle cures.’”

—Bess Lovejoy, author of Rest in Pieces: The Curious Fates of Famous Corpses

“Entertaining and informative.” —Publishers Weekly

"[A] fantastical (and morbidly funny) glimpse into the history of medicine.' —Buzzfeed.com

- On Sale

- Oct 17, 2017

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Workman Publishing Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780761189817

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use