Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

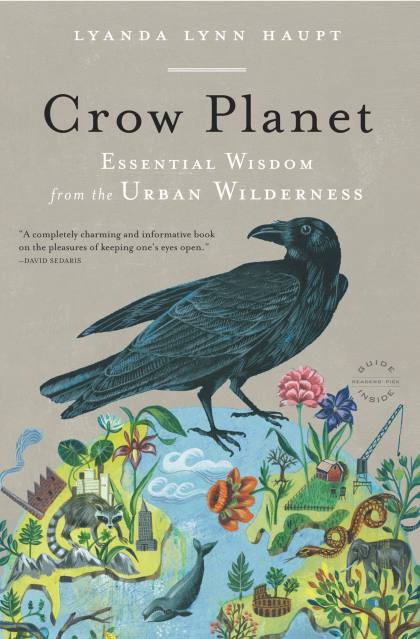

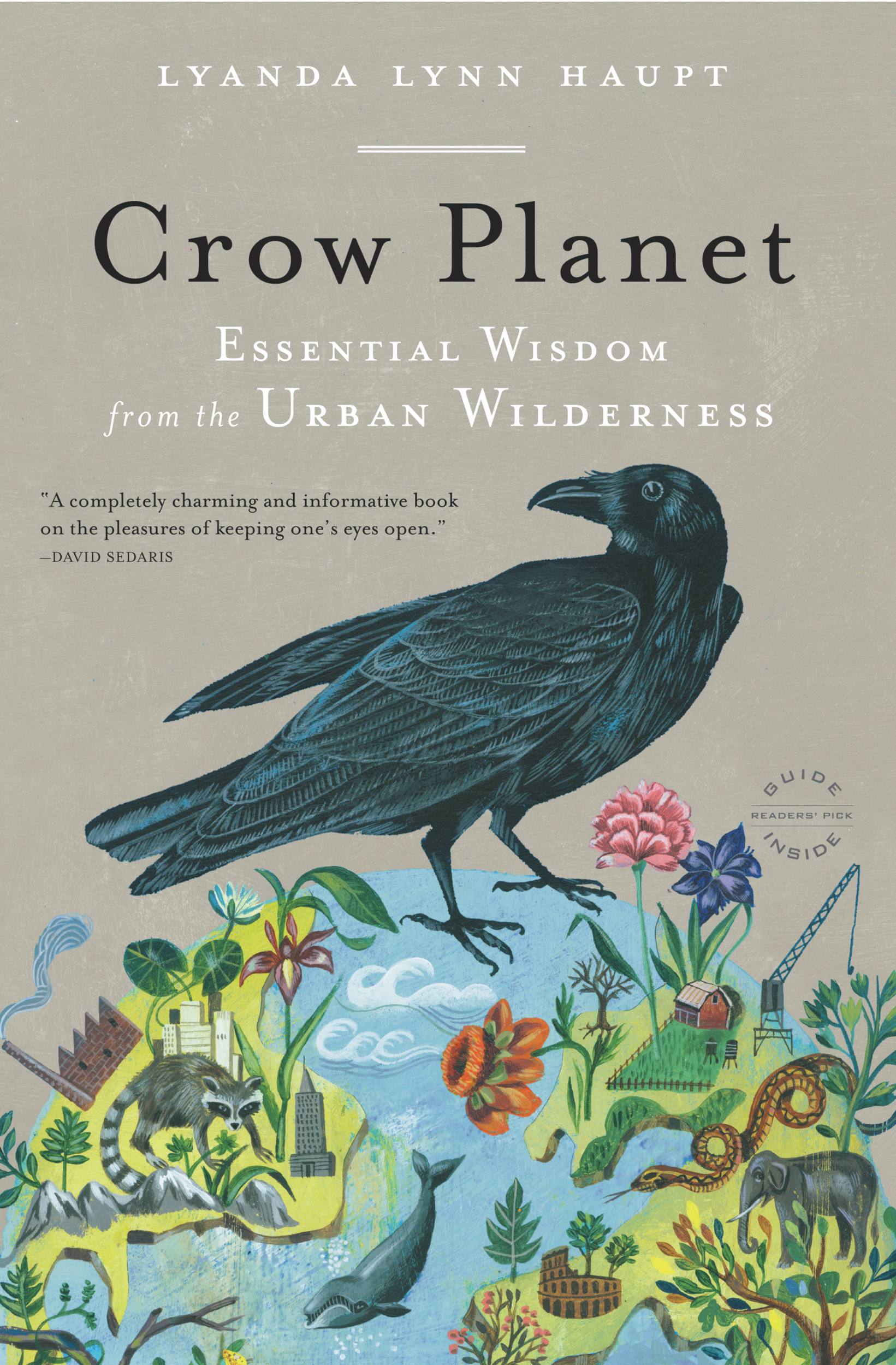

Crow Planet

Essential Wisdom from the Urban Wilderness

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$6.99Price

$8.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $6.99 $8.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 27, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

There are more crows now than ever. Their abundance is both an indicator of ecological imbalance and a generous opportunity to connect with the animal world. Crow Planet reminds us that we do not need to head to faraway places to encounter “nature.” Rather, even in the suburbs and cities where we live we are surrounded by wild life such as crows, and through observing them we can enhance our appreciation of the world’s natural order.

Crow Planet richly weaves Haupt’s own “crow stories” as well as scientific and scholarly research and the history and mythology of crows, culminating in a book that is sure to make readers see the world around them in a very different way.

Crow Planet richly weaves Haupt’s own “crow stories” as well as scientific and scholarly research and the history and mythology of crows, culminating in a book that is sure to make readers see the world around them in a very different way.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jul 27, 2009

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Little Brown Spark

- ISBN-13

- 9780316053396

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use