By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

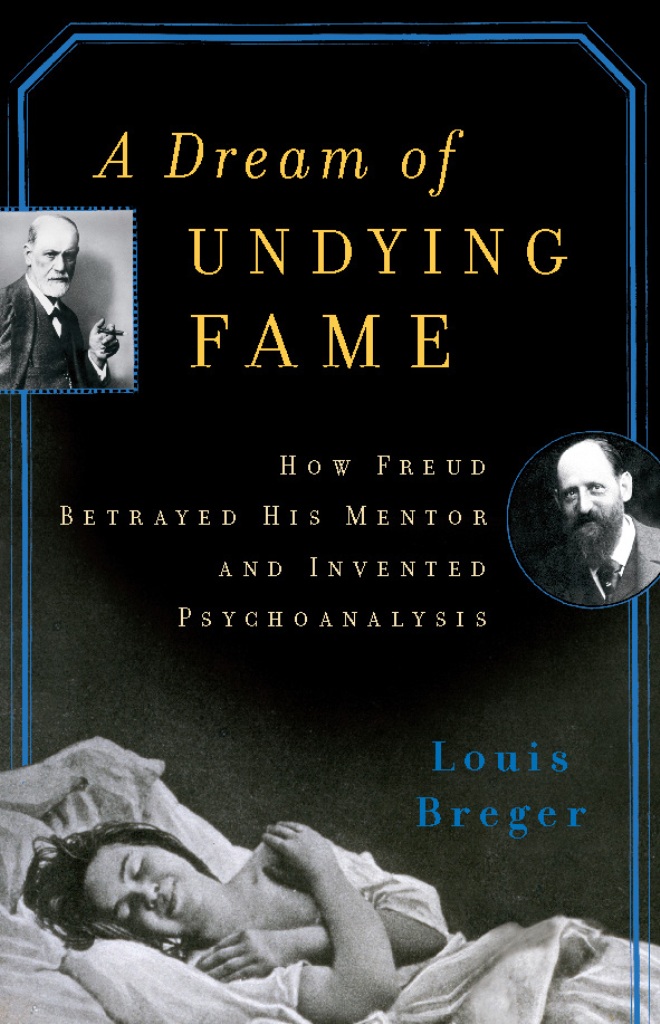

A Dream of Undying Fame

How Freud Betrayed His Mentor and Invented Psychoanalysis

Contributors

By Louis Breger

Formats and Prices

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $15.99 $20.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 25, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In A Dream of Undying Fame, renowned psychologist Louis Breger narrates the story behind the creation of Studies as well as the case of Anna O., which helped contribute to Freud’s definition of “neurosis.” Breger reveals that Freud’s own self-mythologizing and history not only affected everything he did in life, but also helped shape his emerging beliefs about psychoanalysis. Illustrating the importance of personality and social context behind an intellectual breakthrough, Breger provides an in-depth look at a field that reshaped our understanding of what it means to be human.

- On Sale

- Aug 25, 2009

- Page Count

- 216 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465019885

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use