Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

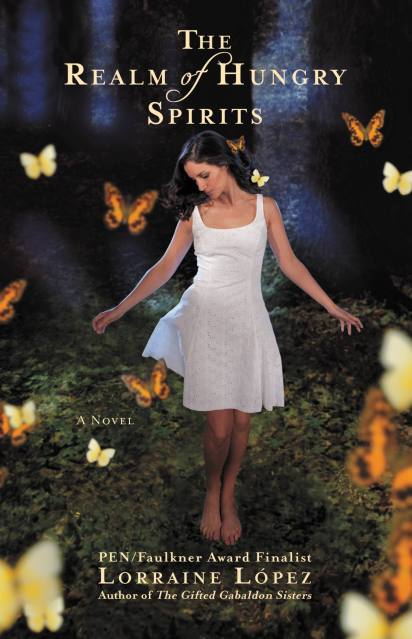

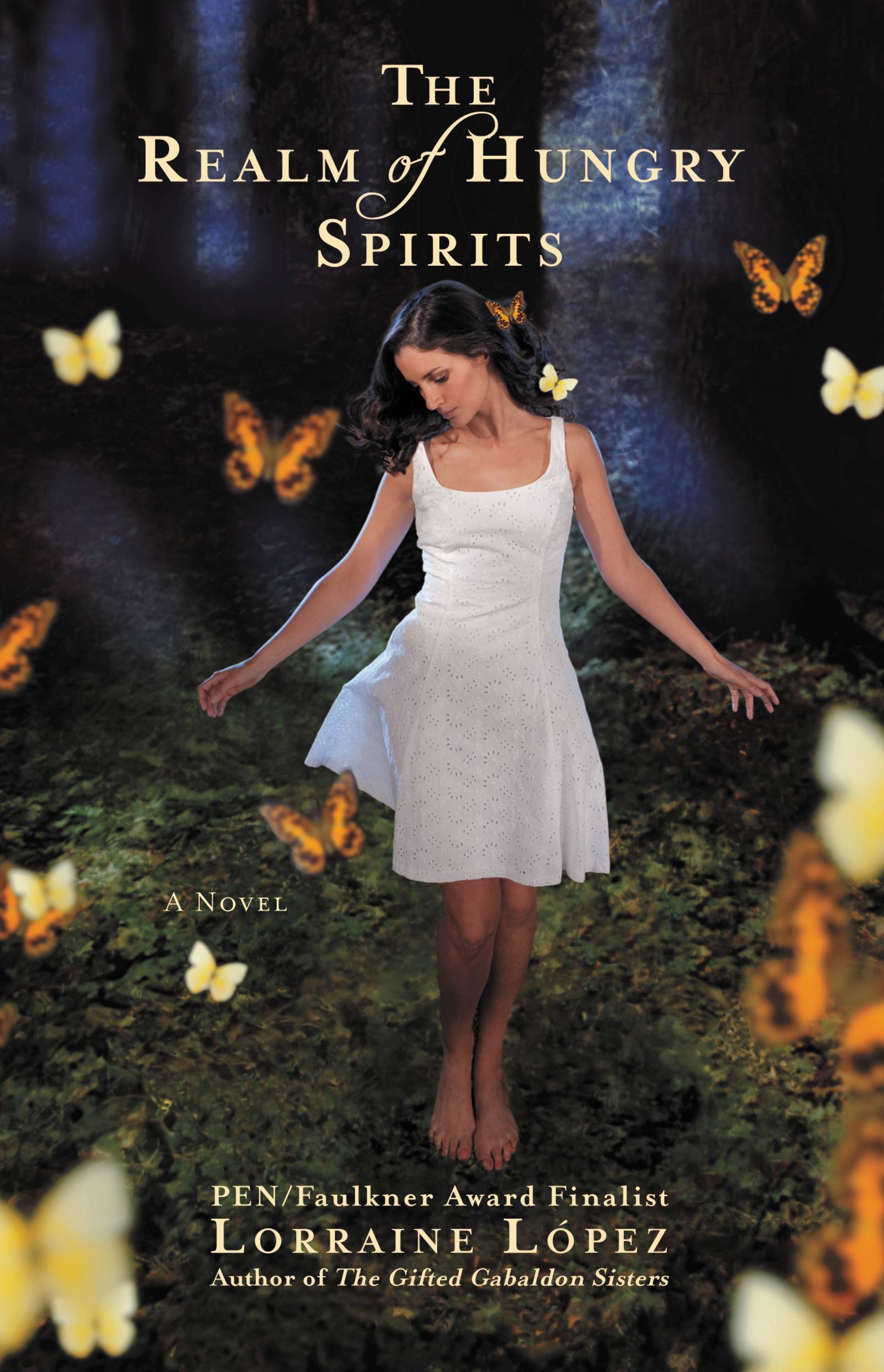

The Realm of Hungry Spirits

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback (Large Print) $24.99 $31.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 2, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The award-winning author of The Gifted Gabaldón Sisters returns with a new novel about a woman who craves solitude, only to find family more fulfilling.

In Buddhism, there is a place where hungry souls gather between lives awaiting rebirth so they can finally satisfy the desires that haunt them.

In the San Fernando Valley, that place is Marina Lucero's house.

The Realm of Hungry Spirits

For Marina Lucero, whose father transformed his life through meditation and whose mother gave hers to a Carmelite convent, spirituality should come easily. It doesn't. After a devastating relationship leaves her feeling lost and alone, she opens her home to a collection of wayward souls– the abused woman next door and her alcoholic sister, her aimless nephew and his broken-hearted best friend. Her house now full but her heart still empty, Marina then turns to the wisdom of Gandhi, the Dalai Lama, even a Santeria priest who wants to cleanse her home.

As Marina struggles to balance the disappointments and delights of daily life, she'll learn that, when it comes to inner peace and those we love, a little chaos can lead to a lot of happiness.

In Buddhism, there is a place where hungry souls gather between lives awaiting rebirth so they can finally satisfy the desires that haunt them.

In the San Fernando Valley, that place is Marina Lucero's house.

The Realm of Hungry Spirits

For Marina Lucero, whose father transformed his life through meditation and whose mother gave hers to a Carmelite convent, spirituality should come easily. It doesn't. After a devastating relationship leaves her feeling lost and alone, she opens her home to a collection of wayward souls– the abused woman next door and her alcoholic sister, her aimless nephew and his broken-hearted best friend. Her house now full but her heart still empty, Marina then turns to the wisdom of Gandhi, the Dalai Lama, even a Santeria priest who wants to cleanse her home.

As Marina struggles to balance the disappointments and delights of daily life, she'll learn that, when it comes to inner peace and those we love, a little chaos can lead to a lot of happiness.

Genre:

- On Sale

- May 2, 2011

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781609418687

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use