By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

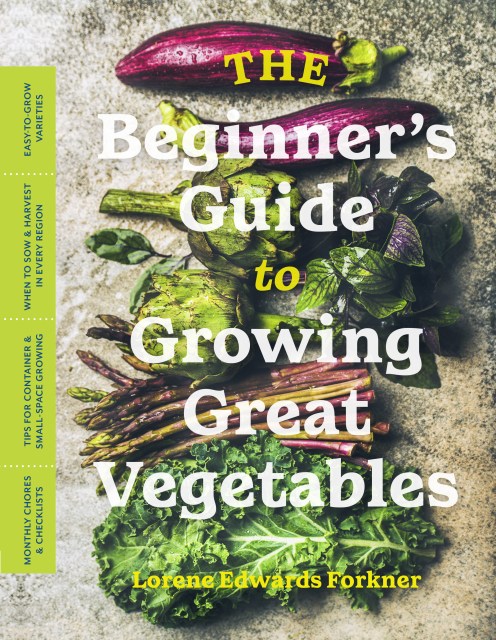

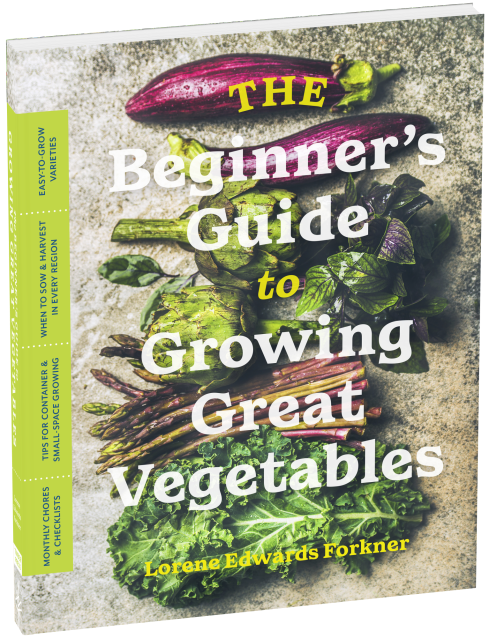

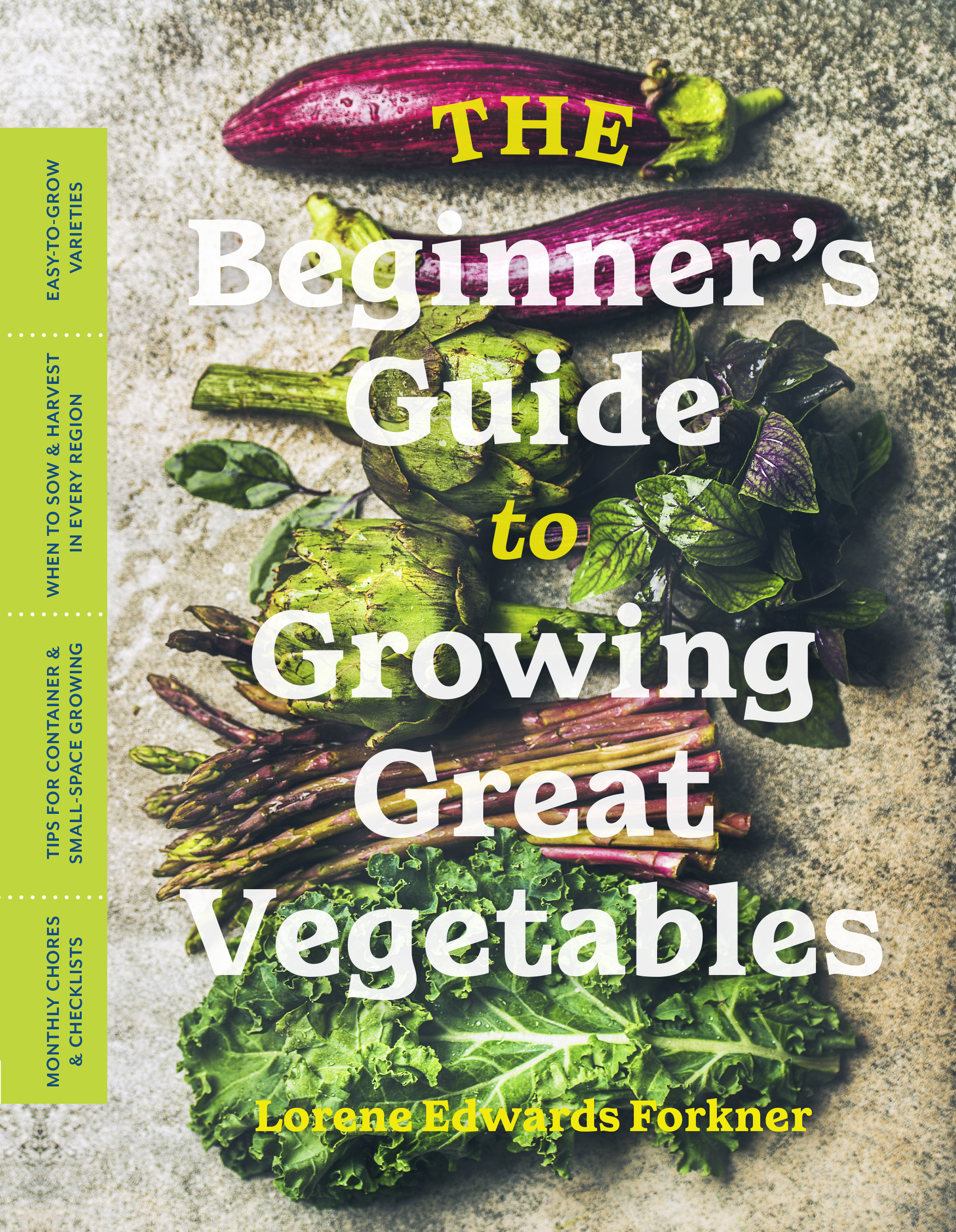

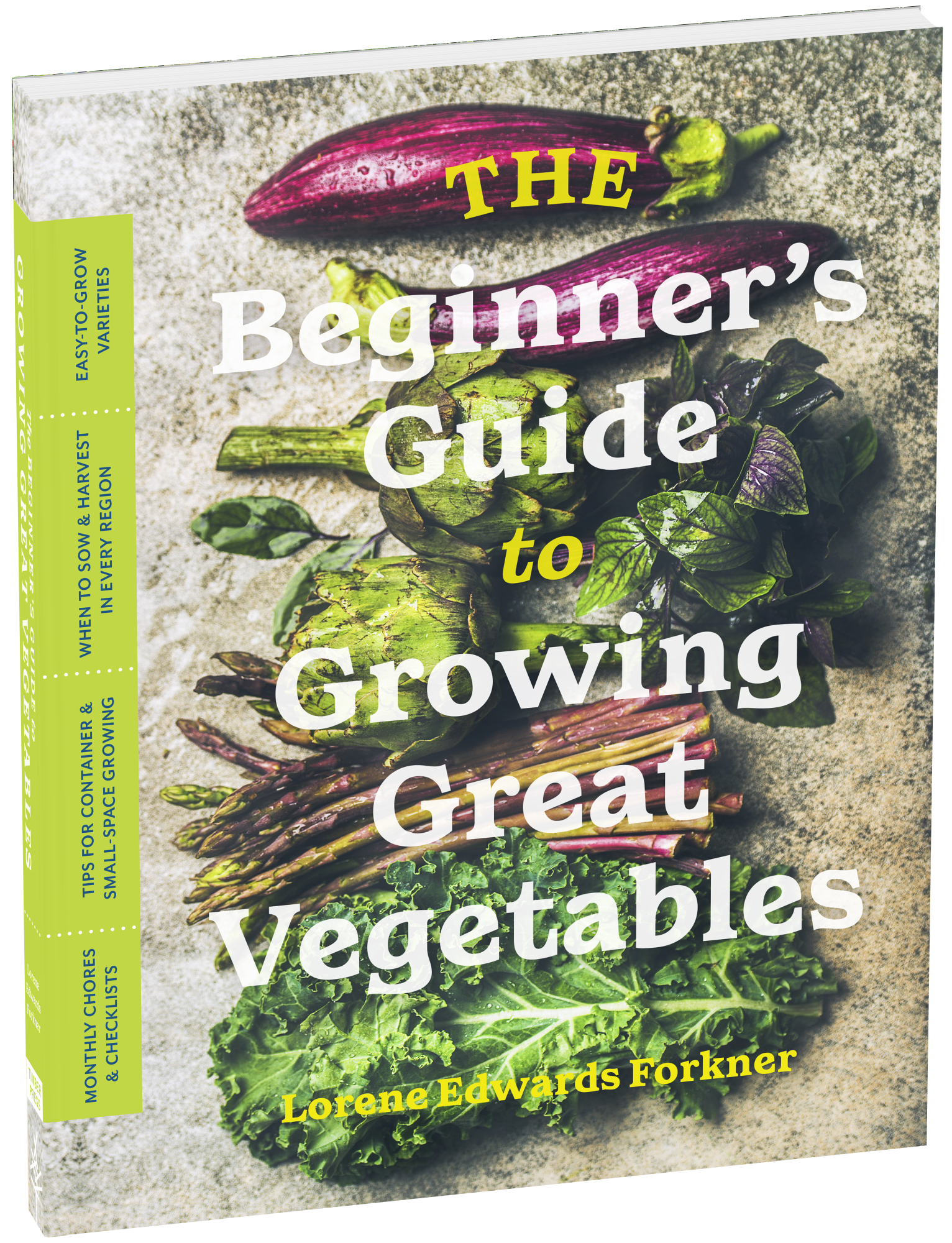

The Beginner’s Guide to Growing Great Vegetables

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 16, 2021

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Timber Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781643260853

Price

$19.95Price

$24.95 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.95 $24.95 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 16, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

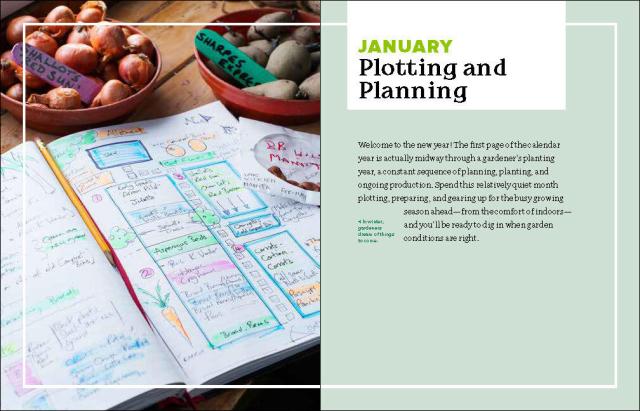

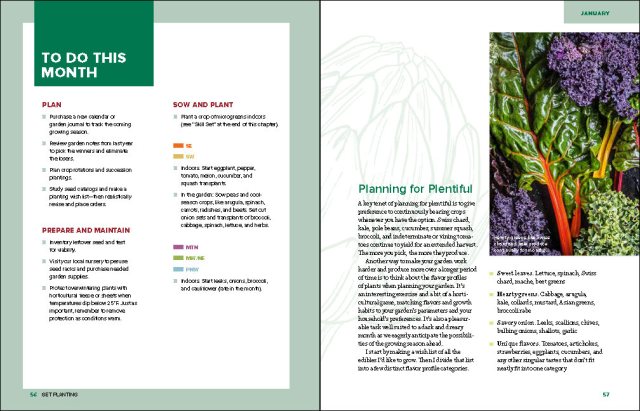

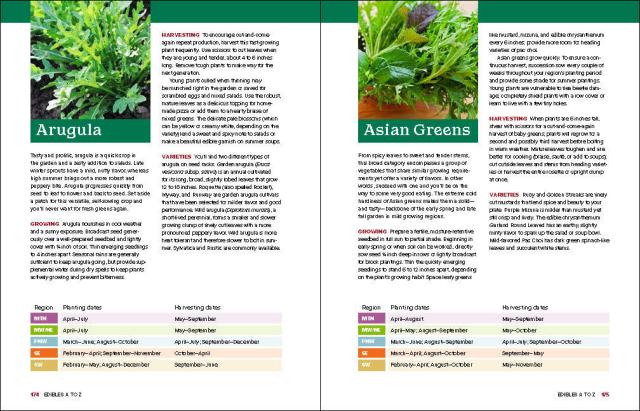

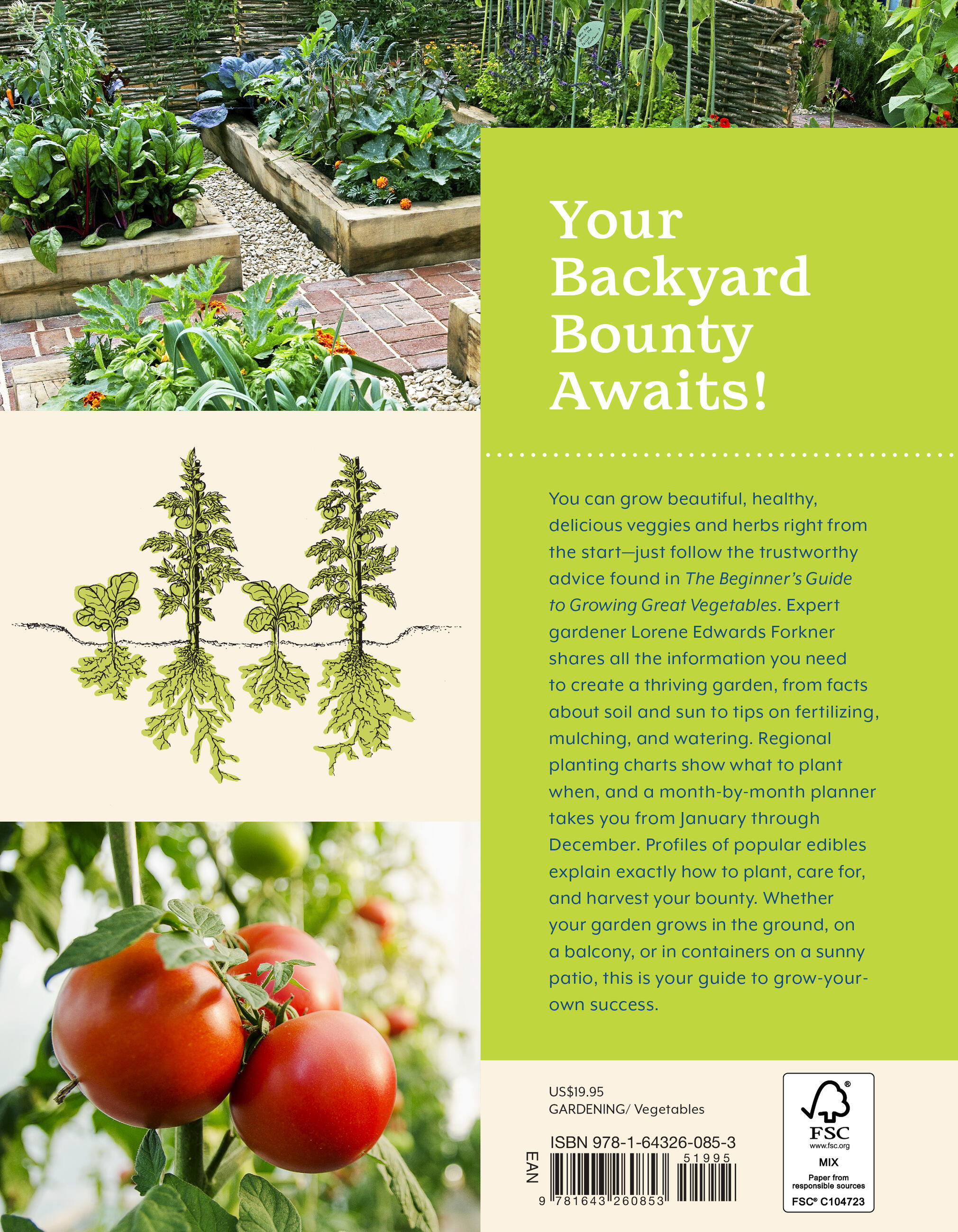

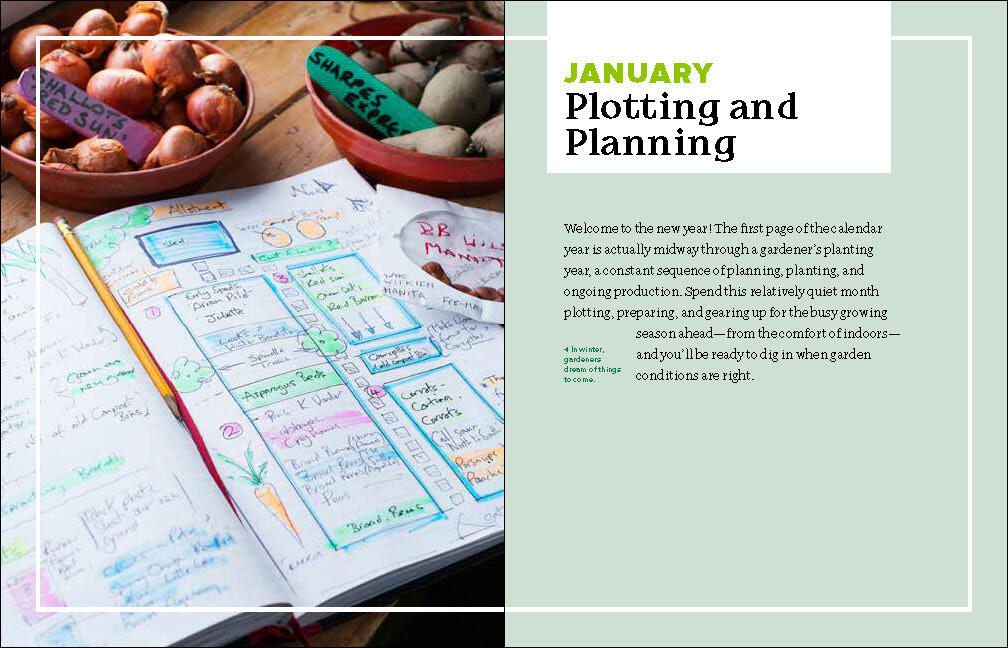

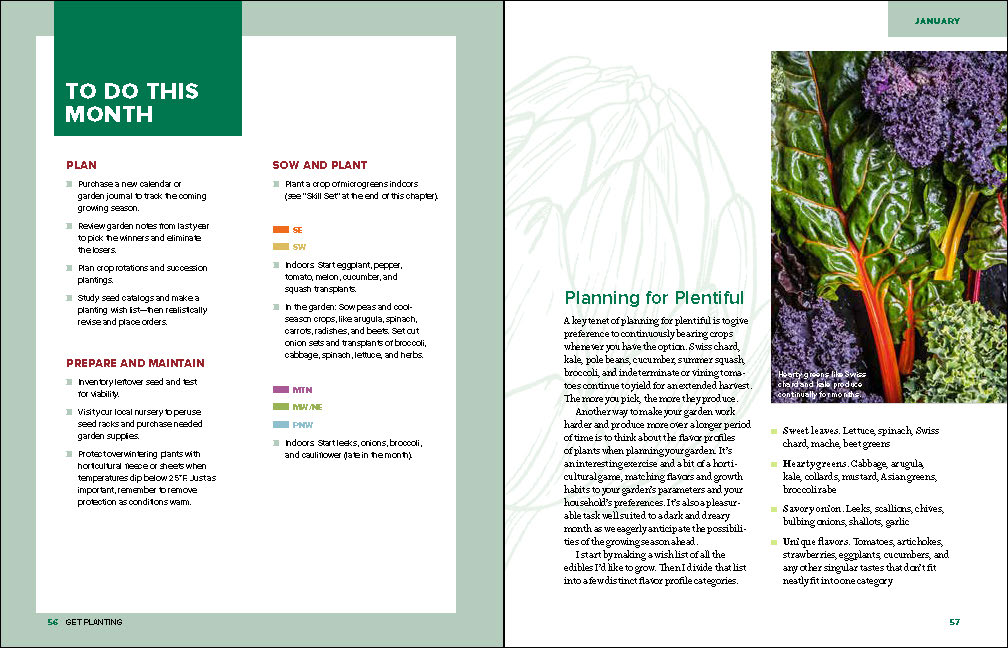

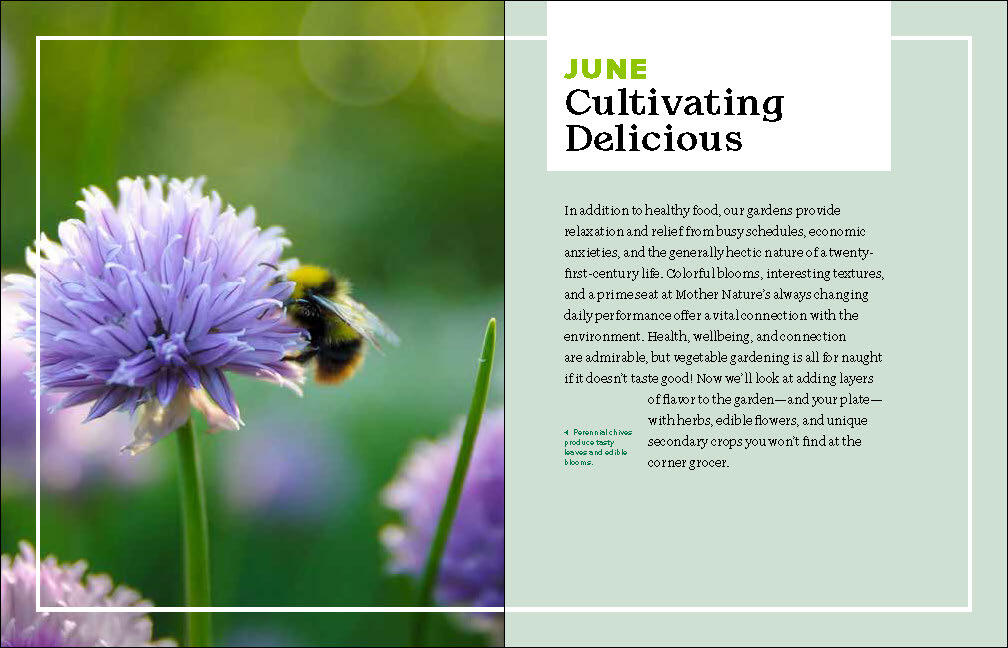

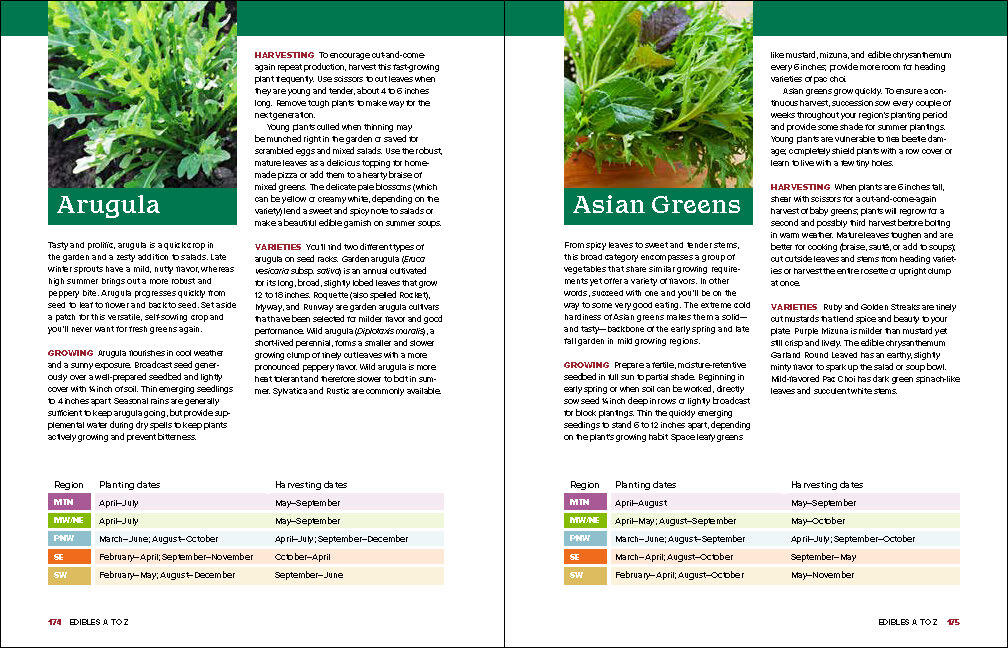

You can grow beautiful, healthy, delicious veggies and herbs right from the start—just follow the trustworthy advice found in The Beginner’s Guide to Growing Great Vegetables. Expert gardener Lorene Edwards Forkner shares all the information you need to create a thriving garden, from facts about soil and sun to tips on fertilizing, mulching, and watering. Regional planting charts show what to plant when, and a month-by-month planner takes you from January through December. Profiles of popular edibles explain exactly how to plant, care for, and harvest your bounty. Whether your garden grows in the ground, on a balcony, or in containers on a sunny patio, this is your guide to grow-your-own success. Your backyard bounty awaits!

Genre:

-

“For new and novice gardeners who want a straightforward, unfussy guide to growing their own food.”Library Journal “Lorene Edwards Forkner offers a comprehensive guide for growing vegetables and herbs filled with hands on advice and time-tested techniques.” —The American Gardener “A comprehensive guide to gardening that goes well beyond being appropriate for just beginners… a refreshing overview with an emphasis on nurturing vegetables and herbs in the ground or in containers.” —The Oregonian

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use