Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

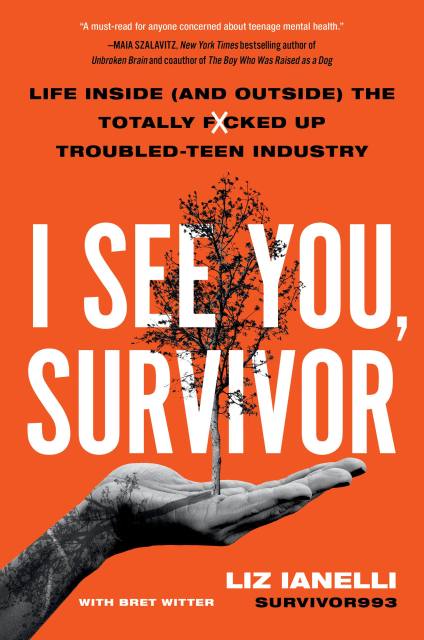

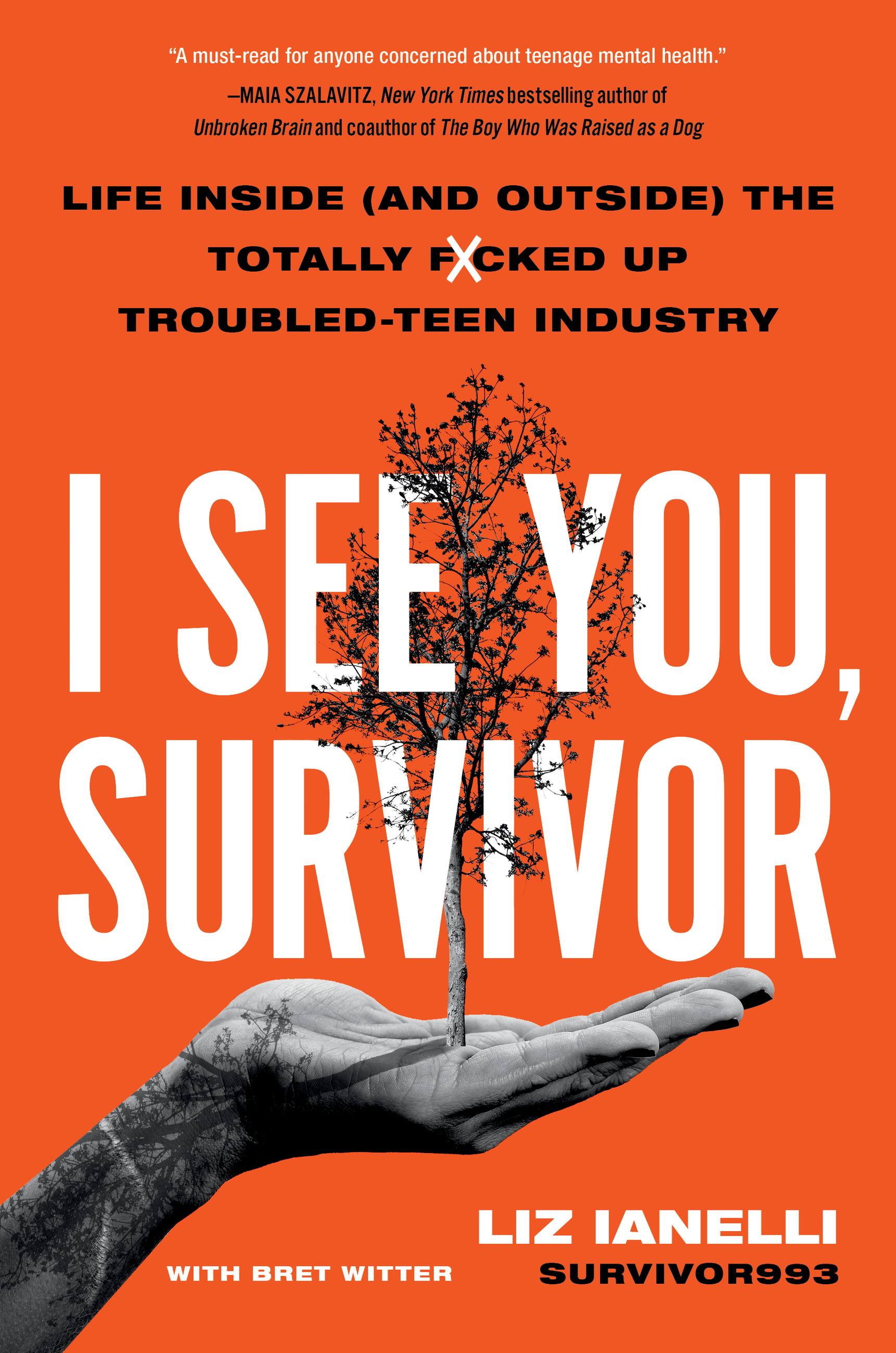

I See You, Survivor

Life Inside (and Outside) the Totally F*cked-Up Troubled Teen Industry

Contributors

By Liz Ianelli

With Bret Witter

Formats and Prices

Price

$29.00Price

$37.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 29, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

"A must read for anyone concerned about teenage mental health." — Maia Szalavitz, NYT bestselilng author of Unbroken Brain co-author of The Boy Who Was Raised as a Dog

A survivor of the Troubled Teen Industry exposes the truth about the dark side of a billion-dollar industry's institutionalized abuse—and shares the story of her own fight for justice.

I See You, Survivor is about what really happened at The Family and what continues to happen at thousands of facilities like it. Beyond the trauma, this book is about triumph, resilience, and an effort to help others, and it conveys Liz’s critical message for every survivor she sees:

“You are not broken. You are not unlovable. And you are not alone. There are millions of us. And I come with a message, for you, for them, for everyone: They act strong, but we are stronger. We are worthy. We are not alone. Speak, and we will be there for you. Speak, because there is power in your testimony. Speak, and we will win.”

This is a book first and foremost for survivors who can find support and community in these stories. It is also for parents, counselors, law makers and others to expose this industry for what it is: child abuse. And how that abuse has consequences for all of us.

Genre:

-

“Searing, profane, horrifying, but ultimately hopeful—read I See You, Survivor to understand how abuse is sold to parents as treatment for “troubled teens” and why these programs must be stopped. Liz’s story is hard to take, but thousands of young people have survived similar attack therapies and many are still being forced into “wilderness programs,” “boot camps,” “emotional growth,” and “therapeutic” boarding schools today. A must-read for anyone concerned about teenage mental health and how systems intended to help can go terribly wrong.”Maia Szalavitz, NYT bestselling author of Unbroken Brain and co-author of The Boy Who Was Raised as a Dog

-

"A ferocious, raw, and inspiring story of triumph over trauma—and a powerful reminder that we must listen to those our society is far too quick to dismiss as broken or lost."Beth Macy, NYT bestselling author of Dopesick

-

“This book is deep. It will get deep into your mind, and deep into your heart. But it’s also fire. Liz Ianelli came here to burn down their lies and save her people, and you can feel her heat on every page. You won’t forget it. You’ll be changed. Because I See You, Survivor issues the same challenge as every great memoir: You heard the triumphs I made out of my pain, my anger, and my failures. Now what are you going to make out of yours?”Chris Wilson, author of The Master Plan

-

“In between bombshell revelations, Ianelli celebrates the resilience of her fellow survivors. Her quest for justice against so-called “tough love” schools that allow abusers to act with near-impunity is incendiary and uncompromising. … this unflinching memoir presents a moving message of triumph over trauma.”Publisher’s Weekly

-

"A devastating explication of widespread overlooked abuse and a call for change that must be heeded."Kirkus Reviews

- On Sale

- Aug 29, 2023

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780306831522

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use