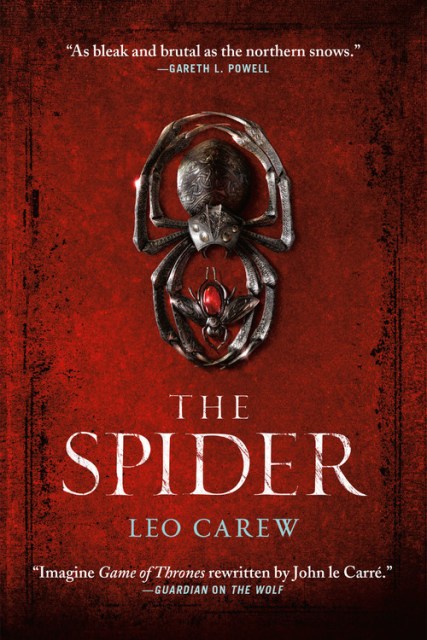

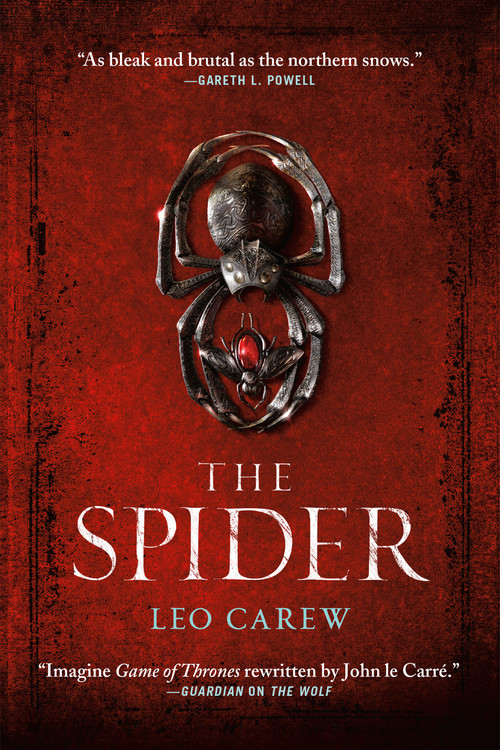

The Spider

Contributors

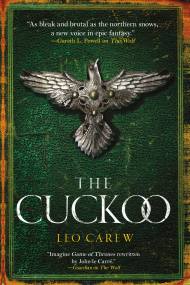

By Leo Carew

Formats and Prices

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 30, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Control of the land under the Northern Sky rests in the balance as two fierce races collide in the sequel to The Wolf, a thrilling and savagely visceral epic fantasy from Leo Carew, an author who “will remind readers of George R. R. Martin, David Gemmell, or . . . Joe Abercrombie.” (Booklist)

Roper, the Black Lord of the north, may have vanquished the Suthern army at the Battle of Harstathur. But the greatest threat to his people lies in the hands of more shadowy forces.

In the south, the disgraced Bellamus bides his time. Learning that the young Lord Roper is planning to invade the southern lands, Bellamus conspires with his Queen to unleash a weapon so deadly it could wipe out Roper’s kind altogether.

And at a time when Roper needs his friends more than ever, treachery from within puts the lives of those he loves in mortal danger . . .

For more from Leo Carew, check out:

Under the Northern Sky

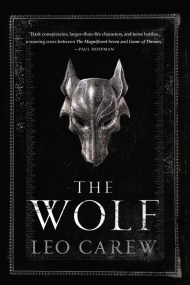

The Wolf

The Spider

Genre:

Series:

- On Sale

- Jul 30, 2019

- Page Count

- 544 pages

- Publisher

- Orbit

- ISBN-13

- 9780316521406

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use