Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

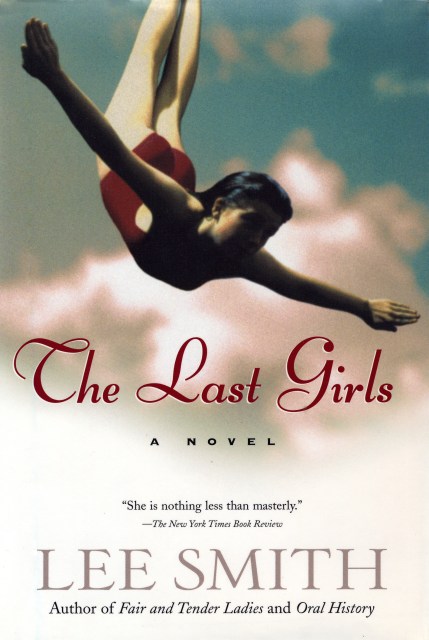

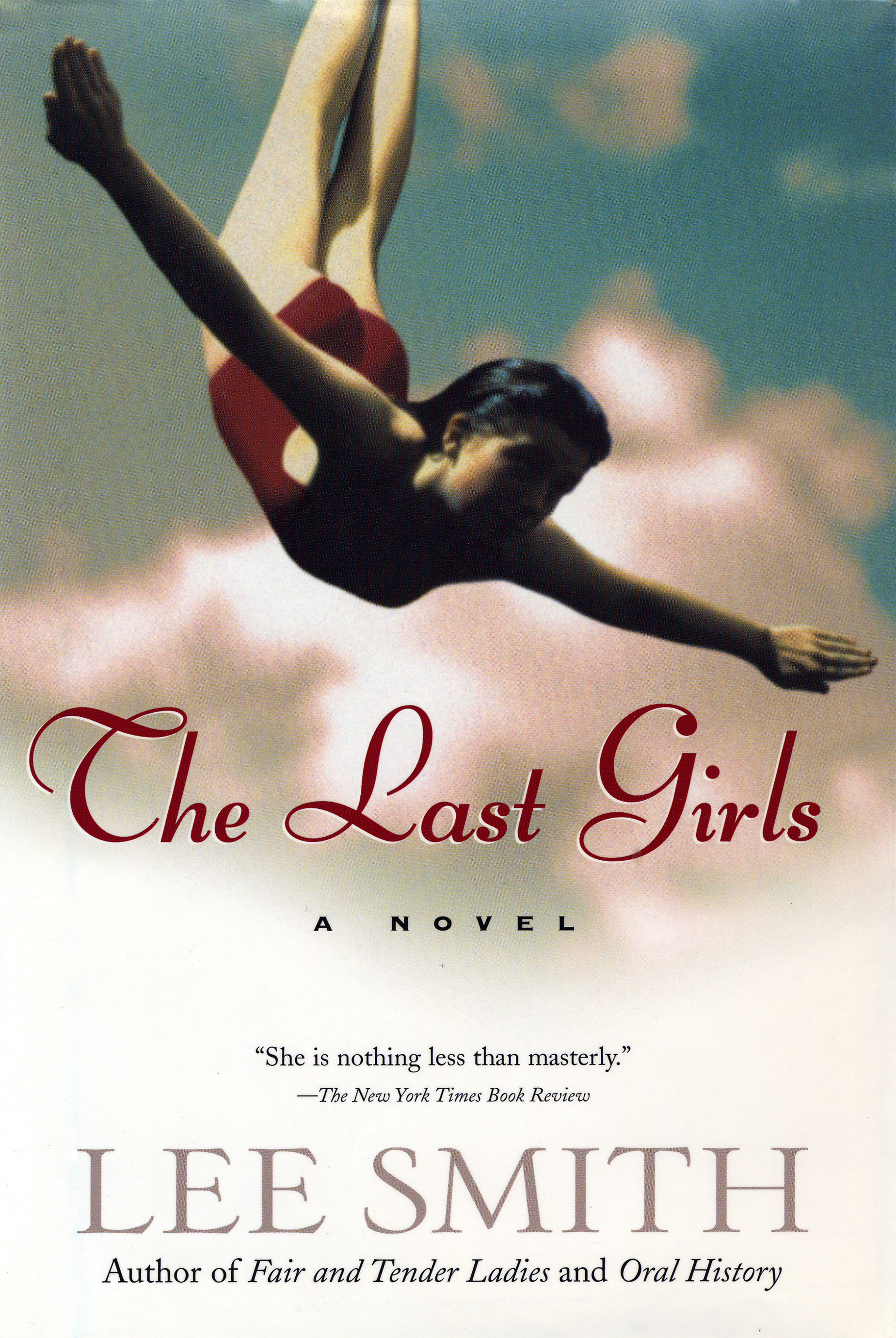

The Last Girls

Contributors

By Lee Smith

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook (Digital original) $12.99 $16.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 12, 2002. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Thirty-five years later, four of those “girls” reunite to cruise the river again. This time it’s on the luxury steamboat, The Belle of Natchez, and there’s no publicity. This time, when they reach New Orleans, they’ll give the river the ashes of a fifth rafter-beautiful Margaret (“Baby”) Ballou.

Revered for her powerful female characters, here Lee Smith tells a brilliantly authoritative story of how college pals who grew up in an era when they were still called “girls” have negotiated life as “women.” Harriet Holding is a hesitant teacher who has never married (she can’t explain why, even to herself). Courtney Gray struggles to step away from her Southern Living-style life. Catherine Wilson, a sculptor, is suffocating in her happy third marriage. Anna Todd is a world-famous romance novelist escaping her own tragedies through her fiction. And finally there is Baby, the girl they come to bury-along with their memories of her rebellions and betrayals.

THE LAST GIRLS is wonderful reading. It’s also wonderfully revealing of women’s lives-of the idea of romance, of the relevance of past to present, of memory and desire.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Aug 12, 2002

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Algonquin Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781565128750

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use