Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

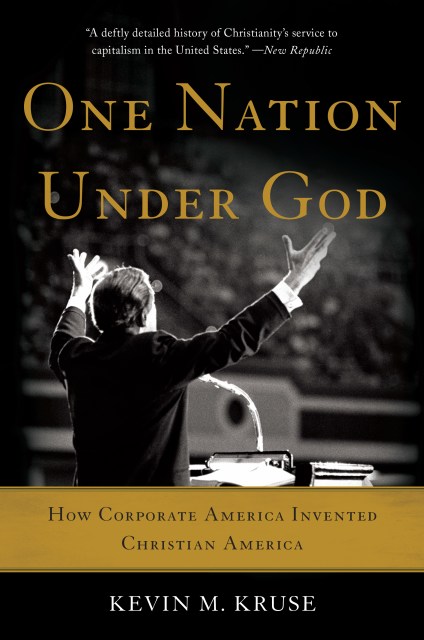

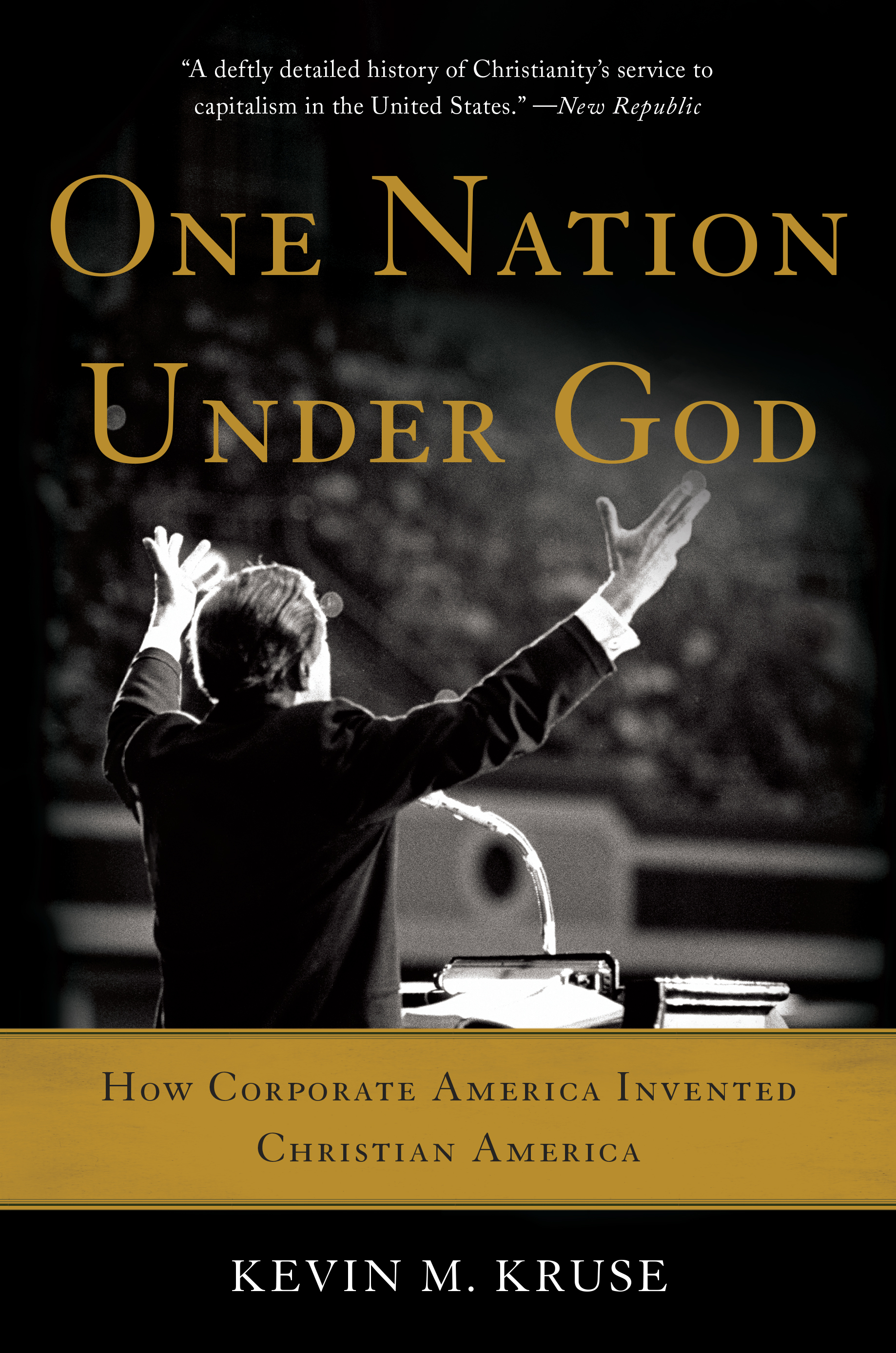

One Nation Under God

How Corporate America Invented Christian America

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover $29.99 $37.50 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 14, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

We’re often told that the United States is, was, and always has been a Christian nation. But in One Nation Under God, historian Kevin M. Kruse reveals that the belief that America is fundamentally and formally Christian originated in the 1930s.

To fight the “slavery” of FDR’s New Deal, businessmen enlisted religious activists in a campaign for “freedom under God” that culminated in the election of their ally Dwight Eisenhower in 1952. The new president revolutionized the role of religion in American politics. He inaugurated new traditions like the National Prayer Breakfast, as Congress added the phrase “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance and made “In God We Trust” the country’s first official motto. Church membership soon soared to an all-time high of 69 percent. Americans across the religious and political spectrum agreed that their country was “one nation under God.”

Provocative and authoritative, One Nation Under God reveals how an unholy alliance of money, religion, and politics created a false origin story that continues to define and divide American politics to this day.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Apr 14, 2015

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465040643

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use