Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

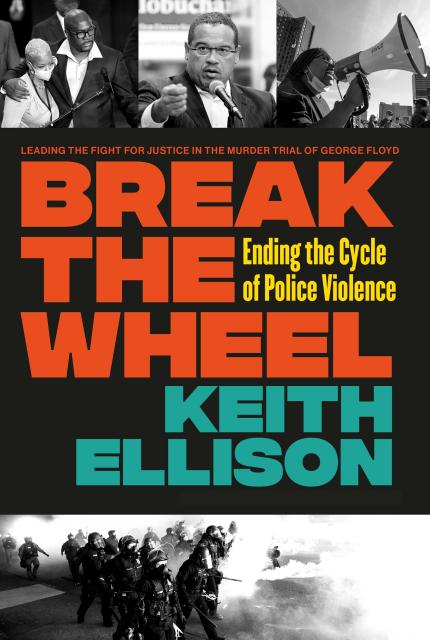

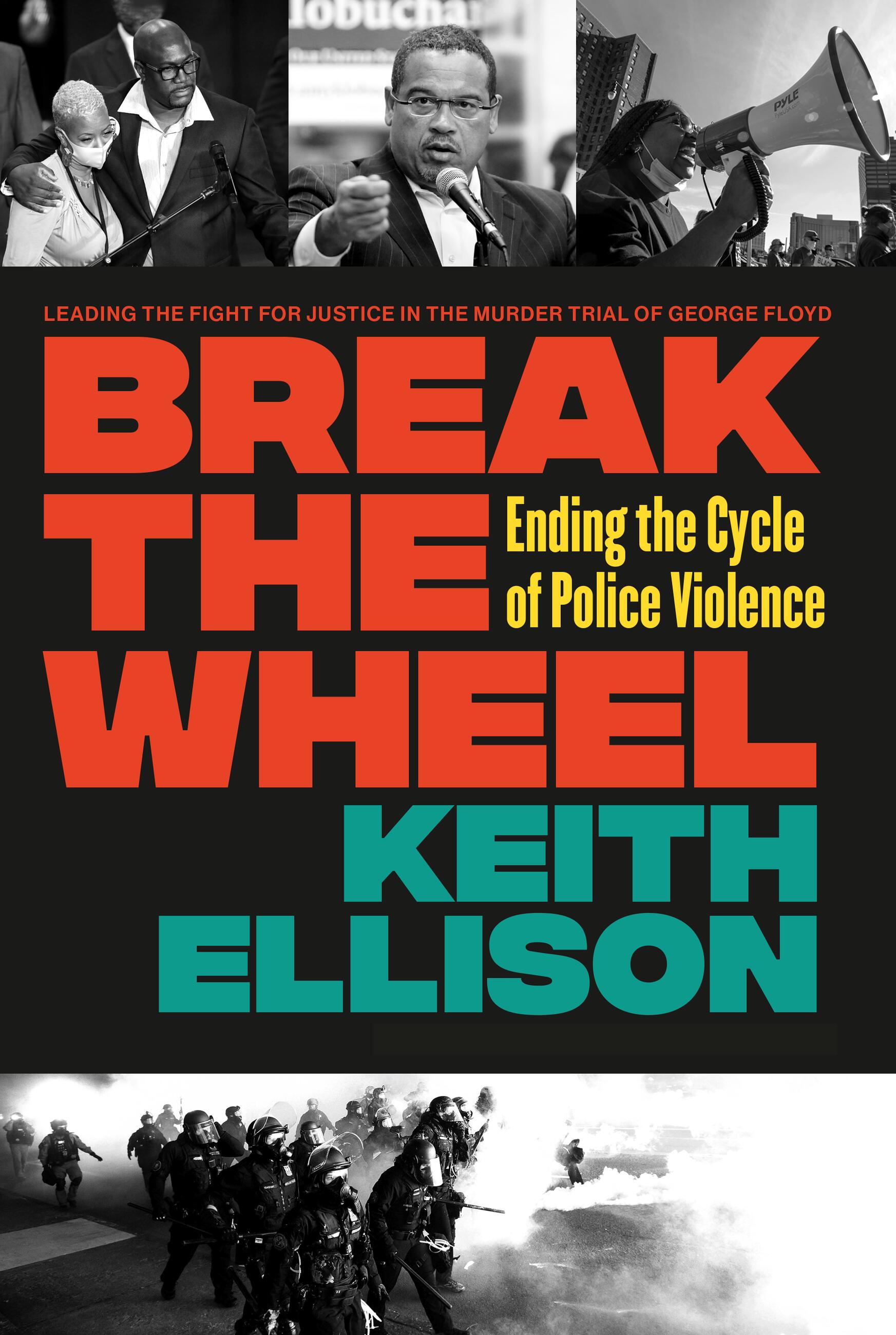

Break the Wheel

Ending the Cycle of Police Violence

Contributors

Foreword by Philonise Floyd

Formats and Prices

Price

$30.00Price

$38.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 23, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

With this powerful and intimate trial diary, Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison asks the key question: How do we break the wheel of police violence and finally make it stop?

The murder of George Floyd sparked global outrage. At the center of the conflict and the controversy, Keith Ellison grappled with the means of bringing justice for Floyd and his family. Now, in this riveting account of the Derek Chauvin trial, Ellison takes the reader down the path his prosecutors took, offering different breakthroughs and revelations for a defining, generational moment of racial reckoning and social justice understanding.

Each chapter of BREAK THE WHEEL goes spoke to spoke along the wheel of the system as Ellison examines the roles of prosecutors, defendants, heads of police unions, judges, activists, legislators, politicians, and media figures, each in his attempt to end this chain of violence and replace it with empathy and shared insight.

Ellison’s analysis of George Floyd’s life and the rich trial context he provides demonstrates that, while it may seem like an unattainable goal, lasting change and justice can be achieved.

-

“An intimate account of a truly consequential courtroom confrontation, in BREAK THE WHEEL, Keith Ellison has written a searing, compelling tale of the struggle for justice. Ellison reminds us well how the death of George Floyd will not—must not—be forgotten and how that tragic death has truly made a difference in our legal system. BREAK THE WHEEL is an unforgettable reading experience.”Eric Holder, former U.S. attorney general

-

“Despite what we all know about the torture and murder of George Floyd, the story of the Herculean legal effort to bring the officers who killed Floyd to justice has never been told—until now. Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison takes us through the compelling story of the painstaking, extraordinary effort he led to prosecute the officers who committed the most infamous racial murder by police in the history of our country.”Sherrilyn Ifill, former president of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund

-

"BREAK THE WHEEL is a compelling tale of standing up for George Floyd. Keith Ellison has produced an engaging, anecdote-laden account that leaves the reader with an increased respect for his pursuit of justice and life in the law."Ben Crump, civil rights attorney

-

“Keith Ellison has written a complete and courageous account of the trial of Derek Chauvin. Without Ellison’s diligence, Chauvin might have walked free. BREAK THE WHEEL engages all stakeholders in a bold and honest conversation.”Van Jones, CNN host

-

“Keith Ellison writes with rare depth, political insight, and true understanding of courtroom drama that comes from being, himself, and outstanding trial lawyer. BREAK THE WHEEL is a riveting and exceptionally frank account of the challenges he faced— and the hard work it took—to bring justice for George Floyd while the whole world was watching.”Barry Scheck, director, The Innocence Project

-

“Keith Ellison’s book is the definitive work on the George Floyd murder trial. As one of his special prosecutors in the case, I saw everything firsthand and cannot imagine a more gripping and incisive account of this historic trial. It’s truly must-read.”Neal Katyal, former U.S. deputy solicitor general

-

"A vital contribution not just to the literature of the Floyd trial, but to that of police reform generally."Kirkus Review

-

“This is an engrossing portrayal about the search for justice in a system that often favors the word and actions of the police, and suggests how we can move forward.”Booklist Review

- On Sale

- May 23, 2023

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781538725634

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use