Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

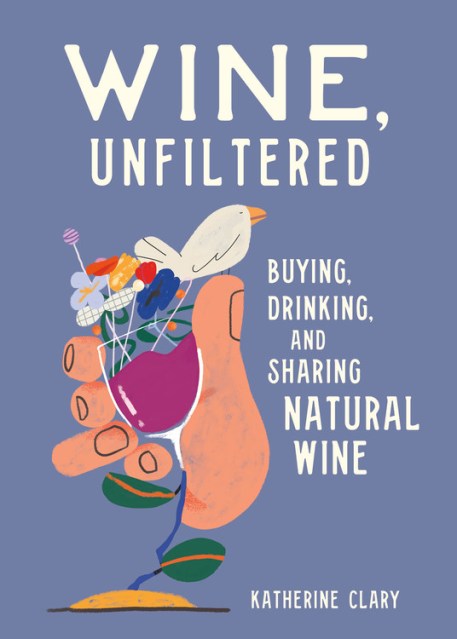

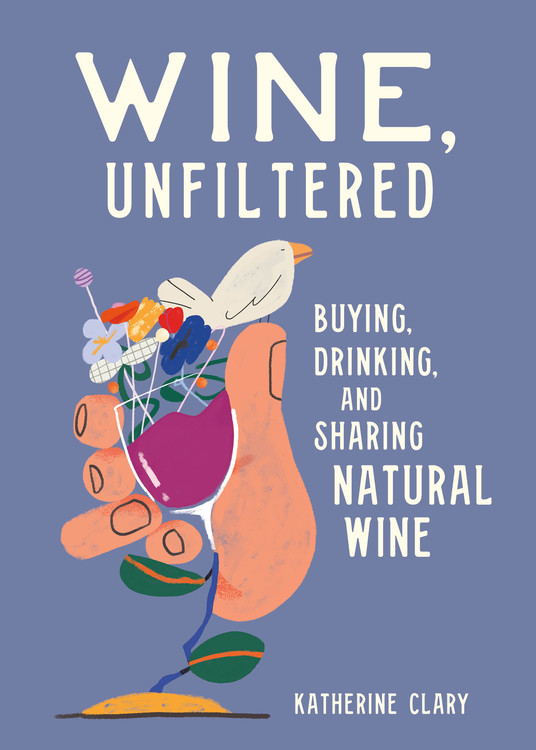

Wine, Unfiltered

Buying, Drinking, and Sharing Natural Wine

Contributors

Illustrated by Sebastian Curi

Formats and Prices

Price

$18.00Price

$23.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $18.00 $23.00 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 28, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A friendly, charming, and beautifully illustrated introduction to the world of natural wine — where to buy it, what it tastes like, how to share it, and why it matters.

What makes a wine “natural”? And why does it matter? In Wine, Unfiltered, Katherine Clary, author and creator of the Wine Zine, tackles these questions and many more — like the difference between organic and biodynamic wines, and whether natural varieties really prevent hangovers — to give readers a holistic picture of the thriving world of natural wine. From grape varietals to legendary vintners to the best way to navigate an unfamiliar wine shop, this accessible, witty book is an irresistible exploration of the cutting edge of wine.

Perfect for both natural wine novices and seasoned drinkers, Wine, Unfiltered offers an unpretentious look at what makes natural wine so special. Sections on growing regions, building your own wine cellar, and how to taste a ‘living wine’ will impart readers with the confidence to finally explain what natural wine is at a party, ask a sommelier a question at a restaurant, or convince a reluctant family member to make the switch from conventional to natural wine. Vital information and nuanced opinions are broken out into digestible bites, alongside bold illustrations, in this essential read for anyone interested in the rapidly expanding world of natural wines.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jul 28, 2020

- Page Count

- 176 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762469963

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use