By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

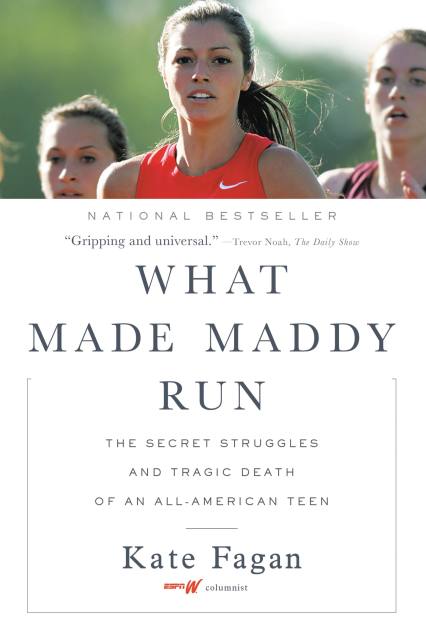

What Made Maddy Run

The Secret Struggles and Tragic Death of an All-American Teen

Contributors

By Kate Fagan

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 1, 2017

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316356534

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 1, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The heartbreaking story of college athlete Madison Holleran, whose life and death by suicide reveal the struggle of young people suffering from mental illness today in this #1 New York Times Sports and Fitness bestseller.

If you scrolled through the Instagram feed of 19-year-old Maddy Holleran, you would see a perfect life: a freshman at an Ivy League school, recruited for the track team, who was also beautiful, popular, and fiercely intelligent. This was a girl who succeeded at everything she tried, and who was only getting started. But when Maddy began her long-awaited college career, her parents noticed something changed. Previously indefatigable Maddy became withdrawn, and her thoughts centered on how she could change her life. In spite of thousands of hours of practice and study, she contemplated transferring from the school that had once been her dream.

When Maddy’s dad, Jim, dropped her off for the first day of spring semester, she held him a second longer than usual. That would be the last time Jim would see his daughter. What Made Maddy Run began as a piece that Kate Fagan, a columnist for espnW, wrote about Maddy’s life. What started as a profile of a successful young athlete whose life ended in suicide became so much larger when Fagan started to hear from other college athletes also struggling with mental illness.

This is the story of Maddy Holleran’s life, and her struggle with depression, which also reveals the mounting pressures young people — and college athletes in particular — face to be perfect, especially in an age of relentless connectivity and social media saturation.

If you scrolled through the Instagram feed of 19-year-old Maddy Holleran, you would see a perfect life: a freshman at an Ivy League school, recruited for the track team, who was also beautiful, popular, and fiercely intelligent. This was a girl who succeeded at everything she tried, and who was only getting started. But when Maddy began her long-awaited college career, her parents noticed something changed. Previously indefatigable Maddy became withdrawn, and her thoughts centered on how she could change her life. In spite of thousands of hours of practice and study, she contemplated transferring from the school that had once been her dream.

When Maddy’s dad, Jim, dropped her off for the first day of spring semester, she held him a second longer than usual. That would be the last time Jim would see his daughter. What Made Maddy Run began as a piece that Kate Fagan, a columnist for espnW, wrote about Maddy’s life. What started as a profile of a successful young athlete whose life ended in suicide became so much larger when Fagan started to hear from other college athletes also struggling with mental illness.

This is the story of Maddy Holleran’s life, and her struggle with depression, which also reveals the mounting pressures young people — and college athletes in particular — face to be perfect, especially in an age of relentless connectivity and social media saturation.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use