Promotion

Use code FALL24 for 20% off sitewide!

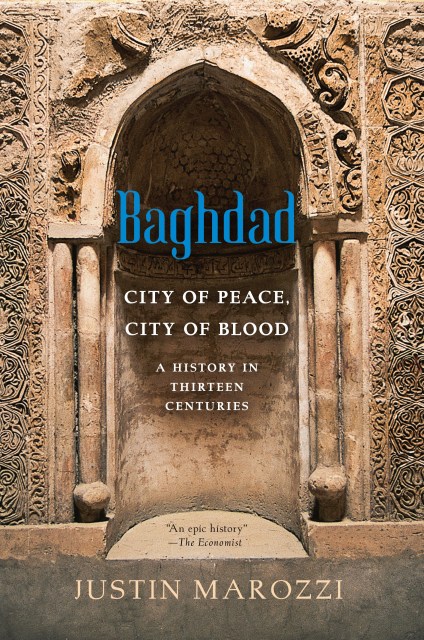

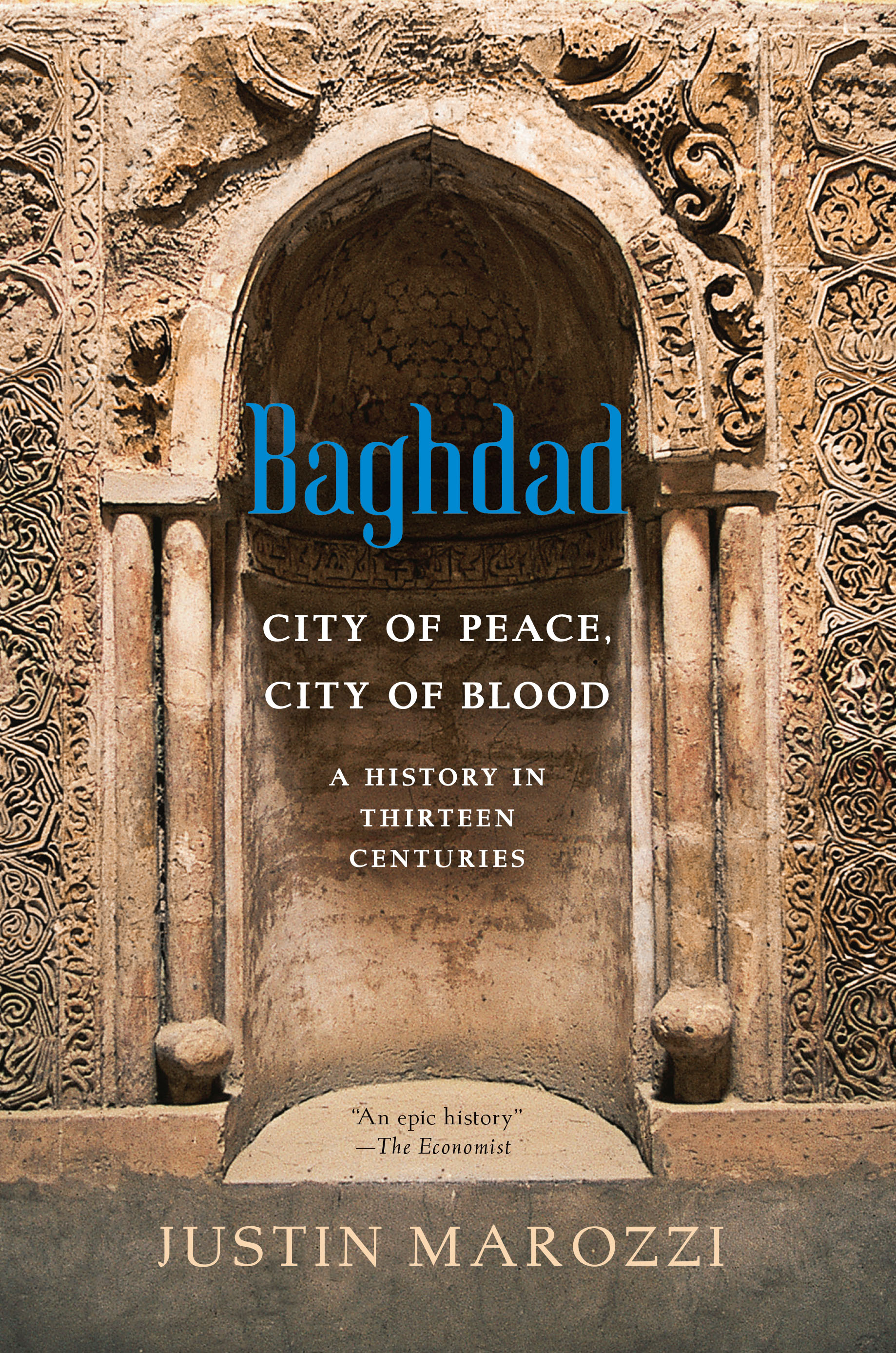

Baghdad

City of Peace, City of Blood--A History in Thirteen Centuries

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$17.99Format

Format:

- ebook $17.99

- Hardcover $32.00

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 4, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Over thirteen centuries, Baghdad has enjoyed both cultural and commercial pre-eminence, boasting artistic and intellectual sophistication and an economy once the envy of the world. It was here, in the time of the Caliphs, that the Thousand and One Nights were set. Yet it has also been a city of great hardships, beset by epidemics, famines, floods, and numerous foreign invasions which have brought terrible bloodshed. This is the history of its storytellers and its tyrants, of its philosophers and conquerors.

Here, in the first new history of Baghdad in nearly 80 years, Justin Marozzi brings to life the whole tumultuous history of what was once the greatest capital on earth.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Nov 4, 2014

- Page Count

- 536 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780306823992

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use