Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

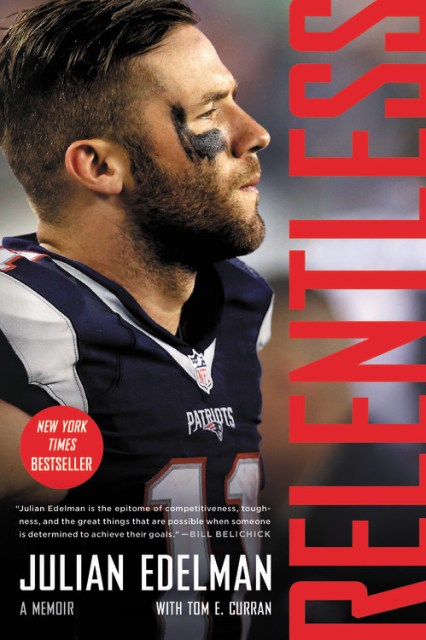

Relentless

A Memoir

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Hardcover $27.00 $35.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 25, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Tom Brady: “It’s a privilege for me to play with someone as special as Julian.”

The Super Bowl champion wide receiver for the New England Patriots shares his inspiring story of an underdog kid who was always doubted to becoming one of the most reliable and inspiring players in the NFL.

When the Patriots were down 28-3 in Super Bowl LI, there was at least one player who refused to believe they would lose: Julian Edelman. And he said so. It wasn’t only because of his belief in his teammates, led by the master of the comeback, his friend and quarterback Tom Brady-or the coaching staff run by the legendary Bill Belichick. It was also because he had been counted out in most of his life and career, and he had proved them all wrong.

Whether it was in Pop Warner football, where his Redwood City, California, team won a national championship; in high school where he went from a 4’10”, 95-pound freshman running back to quarterback for an undefeated Woodside High team; or college, where he rewrote records at Kent State as a dual-threat quarterback, Edelman far exceeded everyone’s expectations. Everyone’s expectations, that is, except his own and those of his father, who took extreme and unorthodox measures to drive Edelman to quiet the doubters with ferocious competitiveness.

When he was drafted by the Patriots in the seventh round, the 5’10” college quarterback was asked to field punts and play wide receiver, though he’d never done either. But gradually, under the tutelage of a demanding coaching staff and countless hours of off-season training with Tom Brady, he became one of the NFL’s most dynamic punt returners and top receivers who can deliver in the biggest games.

Relentless is the story of Edelman’s rise, and the continuing dominance of the Patriot dynasty, filled with memories of growing up with a father who was as demanding as any NFL coach, his near-constant fight to keep his intensity and competitiveness in check in high school and college, and his celebrated nine seasons with the Patriots. Julian shares insights into his relationships and rivalries, and his friendships with teammates such as Tom Brady, Wes Welker, Matt Slater, and Randy Moss. Finally, he reveals the story behind “the catch” and life on the inside of a team for the ages.

Inspiring, honest, and unapologetic, Relentless proves that the heart of a champion can never be measured.

Genre:

-

"What Julian has done from the time he entered the league is nothing short of remarkable. He is the epitome of competitiveness, toughness, and the great things that are possible when someone is determined to achieve their goals."Bill Belichick

-

"Going from being a seventh-round pick to being a great player is a credit to Julian and really one of the most amazing transformations I've seen in this league. To go from a college quarterback, to a pro receiver, then to a great pro receiver? I don't know how many guys that have done that as well as Julian has....It's a privilege for me to play with someone as special as him. I always think I get much more out of my teammates than they get out of me in terms of the relationship and what it means for me to see them grow and succeed. I'm just so proud of him and everything he has accomplished and will continue to accomplish because I know that he's not done. He's got a lot of work he still wants to do."Tom Brady

-

"Julian has told me one of the reasons he's had success is the way his parents have always been there for him. Being firm and having expectations, but doing it with love and making him understand the hard work that goes along with becoming successful. If you're privileged to have a parent or a mentor guiding you to have great love and respect, I think it gets you through the hard times and helps motivate you to greater things. Julian is a testament to that."Robert Kraft

- On Sale

- Sep 25, 2018

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316479868

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use