By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

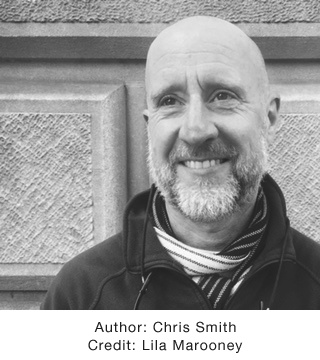

The Daily Show (The Book)

An Oral History as Told by Jon Stewart, the Correspondents, Staff and Guests

Contributors

Foreword by Jon Stewart

By Chris Smith

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 10, 2017

- Page Count

- 480 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781455565368

Price

$18.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 10, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

For almost seventeen years, The Daily Show with Jon Stewart brilliantly redefined the borders between television comedy, political satire, and opinionated news coverage. It launched the careers of some of today’s most significant comedians, highlighted the hypocrisies of the powerful, and garnered 23 Emmys. Now the show’s behind-the-scenes gags, controversies, and camaraderie will be chronicled by the players themselves, from legendary host Jon Stewart to the star cast members and writers-including Samantha Bee, Stephen Colbert, John Oliver, Steve Carell, Lewis Black, Jessica Williams, John Hodgman, and Larry Wilmore-plus some of The Daily Show‘s most prominent guests and adversaries: John and Cindy McCain, Glenn Beck, Tucker Carlson, and many more.

This oral history takes the reader behind the curtain for all the show’s highlights, from its origins as Comedy Central’s underdog late-night program hosted by Craig Kilborn to Jon Stewart’s long reign to Trevor Noah’s succession, rising from a scrappy jester in the 24-hour political news cycle to become part of the beating heart of politics-a trusted source for not only comedy but also commentary, with a reputation for calling bullshit and an ability to effect real change in the world.

Through years of incisive election coverage, Jon Stewart’s emotional monologue in the wake of 9/11, his infamous confrontation on Crossfire, passionate debates with President Obama and Hillary Clinton, feuds with Bill O’Reilly and Fox, the Indecisions, Mess O’Potamia, and provocative takes on Wall Street and racism, The Daily Show has been a cultural touchstone. Now, for the first time, the people behind the show’s seminal moments come together to share their memories of the last-minute rewrites, improvisations, pranks, romances, blow-ups, and moments of Zen both on and off the set of one of America’s most groundbreaking shows.

-

"Zippy, smart."New York (magazine)

-

"Readers of this compelling history will appreciate the sweat behind every joke."Washington Post

-

"Mr. Smith's book feels like a visit to a distant time."New York Times

-

"[A] substantial, many-faceted oral history....This superbly well-edited choral work illuminates the enormous effort, creativity, collaboration, and hustle required for producing a hilarious, news-focused, four-times-a-week comedy show and the chutzpah necessary for taking on the powers-that-be."Booklist

-

"Sometimes our book dreams get answered....If you ever longed to be in the room for epic moments like Stewart's post-9/11 on-air address, his grudge matches with Fox News, the famous Indecision presidential election coverage and more, this is your printed word moment of zen.Detroit Free Press

-

"Deftly recount[s] the way Stewart's sensibilities, political realities (and unrealities), defining events like 9/11, advances in technology and changes in the television news landscape moved the show from spectator to player."USA Today

-

"Smith digs deep into the show's ascendance and cultural influence as if he was one of the show's meticulous fact-checking news-tape researchers...Smith lets the show's stars, crew, and guests tell the show's unvarnished history. Fortunately, most every one interviewed-from Stephen Colbert to longtime showrunner Ben Karlin to Sen. John McCain-possesses an A-plus wit...it doesn't flinch from digging into the show's most contentious moments... in the Age of Trump, the time has never been better to delve into the minds of the masters who became a vital part of our democracy."Entertainment Weekly

-

"Smith gives readers sound bites from some smart, funny and self-aware people waxing rhapsodic about their 'let's put on a show' adventures...the seeming candor of Stewart in particular gives the book a refreshing amount of depth, particularly regarding backstage drama...the real measure of the show and the book that bears its name is, did it have a point, and, moreso, was it funny in making it. The answer, on both counts, is a resounding, laugh-out-loud 'yes.'"Chicago Tribune

-

"Comedy Central's The Daily Show was a cultural phenomenon, and now it gets the oral history it deserves...Smith tells the show's story through artfully arranged first-person recollections. ..it is more than a collection of famous moments, but rather a work of distinctive, original social commentary."The National Book Review

-

"There is solace in this chatty and highly informative tome....THE DAILY SHOW (THE BOOK) is like eating popcorn, in that it's light and fun and easy to consume....the book is a love letter to the people that built The Daily Show and make it work night after night."Vulture

-

"Lively... Smith deftly combines narrative with the recollections of people involved with the show at every level, ranging from boldface names like John McCain to correspondents like Stephen Colbert and Ed Helms....An intimate and entertaining look at a fake-news program whose caustic, witty alchemy remains missed by many."Kirkus Reviews

-

"This is a fascinating history of a cultural phenomenon and the people who powered it. Be aware that, like the show, there is plenty of cursing in this book."Provo City Library Staff Reviews

-

"A must-read for the show's fans and those aspiring to a career in comedy or television."Library Journal

-

"Wonderfully compiled...Certainly if you are a fan of the show you must read THE DAILY SHOW (THE BOOK)...it is a sincere blast to relive its finest moments and understand how it was achieved and more importantly remember how much it was a major part of the democratic process...Bravo, Mr. Smith."Reality Check News & Information Desk

-

"The Daily Show was so obviously the signature TV series of its generation that this book's rare carping voices are almost a relief, in that keeping-things-honest way. If damn near everyone else sounds a bit in awe of what their unlikely Godfather wrought, no wonder."Barnes & Noble Review

-

"Stewart even contributed the introduction. But this isn't a sanitized history. There's plenty of warts and all (and some fun hijinks as well). It's also a smart look at the business of TV and how 24-hour news channels and the rise of conservative media have changed our political culture."Hollywood Reporter

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use