By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

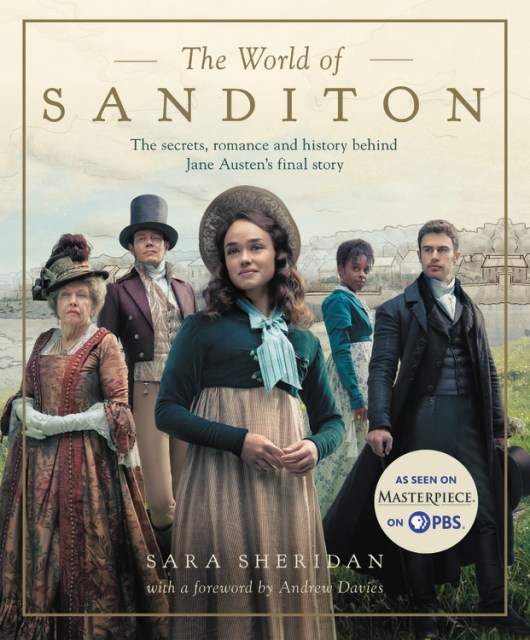

The World of Sanditon: The Official Companion

Contributors

By Sara Sheridan

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Dec 10, 2019

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538734711

Price

$40.00Price

$50.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $40.00 $50.00 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 10, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Sanditon, the final novel Austen was working on before her death, has been given an exciting conclusion, and will be brought to a primetime television audience on PBS/Masterpiece for the very first time by Emmy and BAFTA Award winning screenwriter Andrew Davies (War & Peace, Mr. Selfridge, Les Misérables, Pride and Prejudice).

This, the official companion to the Masterpiece series, contains everything a fan could want to know. It explores the world Austen created, along with fascinating insights about the period and the real-life heartbreak behind her final story. And it offers location guides, behind the scenes details, and interviews with the cast, alongside beautiful illustrations and set photography.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use