Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

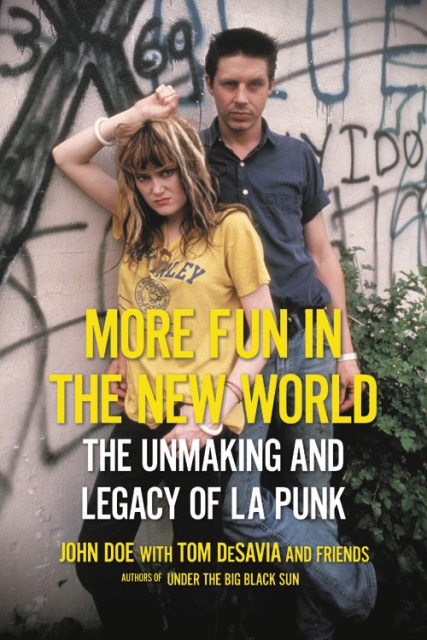

More Fun in the New World

The Unmaking and Legacy of L.A. Punk

Contributors

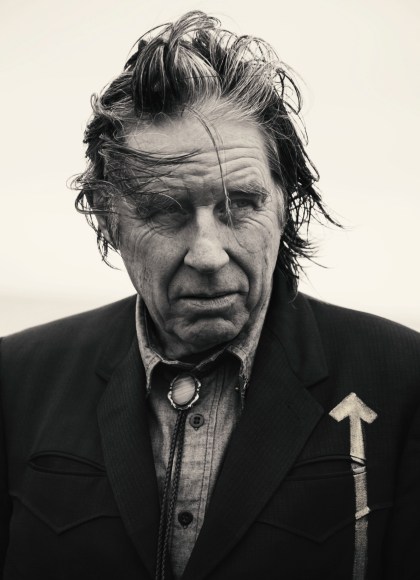

By John Doe

By Tom DeSavia

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 1, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

This sequel to Grammy-nominated bestseller Under the Big Black Sun continues the up-close and personal account of the L.A. punk scene—and includes fifty rare photos.

Picking up where Under the Big Black Sun left off, More Fun in the New World explores the years 1982 to 1987, covering the dizzying pinnacle of L.A.'s punk rock movement as its stars took to the national—and often international—stage. Detailing the eventual splintering of punk into various sub-genres, the second volume of John Doe and Tom DeSavia's west coast punk history portrays the rich cultural diversity of the movement and its characters, the legacy of the scene, how it affected other art forms, and ultimately influenced mainstream pop culture. The book also pays tribute to many of the fallen soldiers of punk rock, the pioneers who left the world much too early but whose influence hasn't faded.

As with Under the Big Black Sun, the book features stories of triumph, failure, stardom, addiction, recovery, and loss as told by the people who were influential in the scene, with a cohesive narrative from authors Doe and DeSavia. Along with many returning voices, More Fun in the New World weaves in the perspectives of musicians Henry Rollins, Fishbone, Billy Zoom, Mike Ness, Jane Weidlin, Keith Morris, Dave Alvin, Louis Pérez, Charlotte Caffey, Peter Case, Chip Kinman, Maria McKee, and Jack Grisham, among others. And renowned artist/illustrator Shepard Fairey, filmmaker Allison Anders, actor Tim Robbins, and pro-skater Tony Hawk each contribute chapters on punk's indelible influence on the artistic spirit.

In addition to stories of success, the book also offers a cautionary tale of an art movement that directly inspired commercially diverse acts such as Green Day, Rancid, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Wilco, and Neko Case. Readers will find themselves rooting for the purists of punk juxtaposed with the MTV-dominating rock superstars of the time who flaunted a "born to do this, it couldn't be easier" attitude that continued to fuel the flames of new music. More Fun in the New World follows the progression of the first decade of L.A. punk, its conclusion, and its cultural rebirth.

Picking up where Under the Big Black Sun left off, More Fun in the New World explores the years 1982 to 1987, covering the dizzying pinnacle of L.A.'s punk rock movement as its stars took to the national—and often international—stage. Detailing the eventual splintering of punk into various sub-genres, the second volume of John Doe and Tom DeSavia's west coast punk history portrays the rich cultural diversity of the movement and its characters, the legacy of the scene, how it affected other art forms, and ultimately influenced mainstream pop culture. The book also pays tribute to many of the fallen soldiers of punk rock, the pioneers who left the world much too early but whose influence hasn't faded.

As with Under the Big Black Sun, the book features stories of triumph, failure, stardom, addiction, recovery, and loss as told by the people who were influential in the scene, with a cohesive narrative from authors Doe and DeSavia. Along with many returning voices, More Fun in the New World weaves in the perspectives of musicians Henry Rollins, Fishbone, Billy Zoom, Mike Ness, Jane Weidlin, Keith Morris, Dave Alvin, Louis Pérez, Charlotte Caffey, Peter Case, Chip Kinman, Maria McKee, and Jack Grisham, among others. And renowned artist/illustrator Shepard Fairey, filmmaker Allison Anders, actor Tim Robbins, and pro-skater Tony Hawk each contribute chapters on punk's indelible influence on the artistic spirit.

In addition to stories of success, the book also offers a cautionary tale of an art movement that directly inspired commercially diverse acts such as Green Day, Rancid, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Wilco, and Neko Case. Readers will find themselves rooting for the purists of punk juxtaposed with the MTV-dominating rock superstars of the time who flaunted a "born to do this, it couldn't be easier" attitude that continued to fuel the flames of new music. More Fun in the New World follows the progression of the first decade of L.A. punk, its conclusion, and its cultural rebirth.

Genre:

-

AMAZON, "BEST BOOKS OF THE MONTH -- NONFICTION"

-

NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW, "BEST MUSIC BOOKS OF THE SUMMER"

-

PASTE MAGAZINE, "BEST AUDIOBOOKS OF 2019"

-

AMAZON, "BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR SO FAR -- HUMOR & ENTERTAINMENT"

-

RACHEL RAY EVERY DAY, "5 Things Rachel Ray is Loving Right Now!"

- On Sale

- Jun 1, 2021

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780306922138

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use